NORFOLK - The guided missile destroyers USS Ross, USS Forrest Sherman, the amphibious dock landing ship USS Fort McHenry and the guided-missile cruiser USS Normandy are safely moored at Naval Station Norfolk. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Jonathan Sunderman

Norfolk, Home To World’s Largest Naval Base, Must Adapt As Waters Rise

This port city is racing to figure out how to deal with harsher storms and elevated sea levels — and it's not alone.

NORFOLK, Va. — On a recent driving tour of this mid-size port city at the southern end of Chesapeake Bay, Christine Morris, the city’s chief resilience officer gave an urbanist’s critique of Tidewater Gardens, a public housing community near downtown and the Elizabeth River.

“It’s just a little too wide, everything’s a little too set back, the buildings are a little too low, and so it loses human scale,” Morris said. “And, by the way, it floods.”

Nuisance flooding is only natural when your city is mostly flat and sits about 13 feet above sea level. Severe weather is increasingly common, she said. So heavy rain can overwhelm the stormwater system and while the precipitation drains away eventually, gravel and other debris can clog the aging sewer infrastructure, making travel on city streets difficult due to high water.

While Norfolk, home to important U.S. Navy operations, commercial ports and rail facilities, doesn’t necessarily face the same kind of inundation risks that below-sea-level New Orleans faces, it is one of the most at-risk cities on the East Coast because of coastal flooding.

But like New Orleans, which has been marking the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, Norfolk also has a complex past, present and future with the water that surrounds it.

“We’re a city that’s flooded for 400 years, but we started to see more intense flooding, more widespread flooding and it’s happening more frequently,” Morris said of Norfolk, Virginia’s second-largest city.

Even minimal hurricanes and Nor’easter storms traveling up the East Coast can send storm surge into Chesapeake Bay and up its coastal inlets, like the Elizabeth River and its tributaries and on into Norfolk, flooding its low-lying areas.

Two other factors aren’t working in the city’s favor: Rising sea levels due to climate change and natural ground subsidence in the Chesapeake Bay region. That combination of factors means Norfolk is flooding more frequently than other parts of the East Coast.

Just as other cities were reminded of their individual exposures to risks from natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina a decade ago, Norfolk officials realized they would need to rethink the city’s shoreline and how to accommodate future floodwaters and higher sea levels.

In such a situation, a port city like Norfolk faces choices of either sinking or swimming—and its economy and future vitality depend on the city’s ability to stay above water.

Between 2007 and 2008, Norfolk began working with Dutch engineering consultant Fugro on a preliminary flooding assessment that considered how to use a combination of infrastructure types—hard, natural and grey (e.g., pipes, pumps, ditches and detention ponds)—to manage water more strategically.

When the remnants of Hurricane Ida passed through the area in November 2009, high-water levels at Sewells Point in Norfolk was measured at 7.75 feet. Hurricane Irene passed through the area in August 2011, and pushed water up to 7.63 feet at the same spot. Although those weren’t record-breaking high-water marks, they served as a reminder of the risks Norfolk faces from the water.

“As waters rise, all coastal communities are going to face what we’re facing right now,” Morris said.

The city applied to be and was later named a pilot municipality for the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities initiative in fall 2013, around the same time Morris was made the city manager’s assistant. She became the city’s chief resilience officer six months later and currently oversees the creation of the city’s resilience strategy to combat the shock of flooding, and related economic stresses. That strategy is scheduled to be released in October.

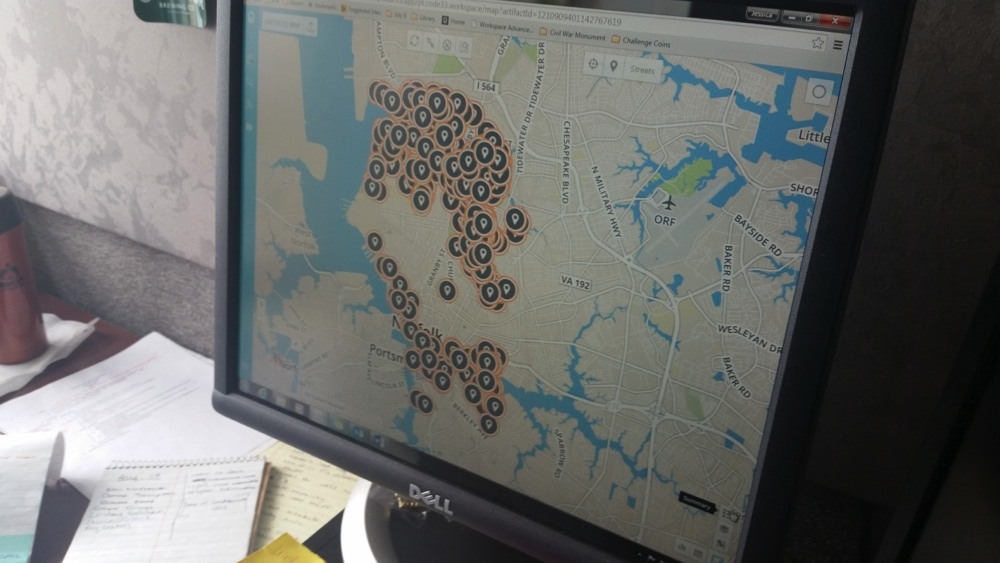

A key player moving forward will undoubtedly be Palo Alto, California-based software company Palantir Technologies, whose data analytics platform is being used by Norfolk to evaluate the flood risk of every land parcel in the city.

“They’re using some modeling and gauges out in the bay to measure how certain areas are affected by flooding based on different sea levels and combining this with city services and data in Palantir to make more data-driven decisions,” Adam Frank, the lead on 100 Resilient Cities’ philanthropy team at Palantir, said in an interview. “In Norfolk, flooding is both an acute shock and a chronic stress that can come about very quickly, but they deal with it on a constant basis.”

In the event of 1-foot of flooding, about 2,000 of the city’s approximately 60,000 parcels would be affected, according to Palantir’s system, which receives data from TITAN—Tidal Inundation Tracking Application for Norfolk—flood gauges in the bay. Every parcel bordering the water floods.

“They’re worried about how flooding has affected the lives of residents and impacted their ability to live in homes and neighborhoods, as well as the business environment of the city,” Frank said. “The city is really invested in trying to become more nimble in being able to live with the water because it’s not going away.”

Palantir's data analysis platform projects about 2,000 of Norfolk's approximately 60,000 parcels of land will suffer in the event of 1 foot of flooding. (Photo by Dave Nyczepir / RouteFifty.com)

Data is the critical element Norfolk needs to continue to adapt to higher water. Its analytics platform is just as important as any physical piece of floodwater management infrastructure.

Aside from the usual suspects—U.S. Census, flood reports and Federal Emergency Management Agency flood map data—Norfolk also regularly updates building permitting, 311 calls for service and code-violation datasets, among others.

When datasets are allowed to talk to each other rather than remain siloed within specific agencies and departments, the city can better forecast impacts. Plotting supermarkets, for instance, reveals how certain levels of flooding can disrupt access to food during an emergency.

Knowing which roads flood first is even more helpful if you know where residents who require home healthcare worker assistance are. That way you can ensure homebound residents can still be accessed by support services if certain streets aren't passable. And if a vulnerable resident is at risk of being cut off by floodwaters, they then can be evacuated to a safer spot.

Norfolk’s floodplain manager requested flood maps from the Federal Emergency Management Agency—issued every five years and released most recently in 2009—be added to Palantir’s platform, and a live weather layer allows Norfolk’s Department of Emergency Preparedness and Response to monitor shelters in relation to different types of storm situations.

But Norfolk has gone from seeing flooding as its sole resilience issue to exploring what it means to be a coastal community, Morris said.

“A lot of people want to talk about flooding challenges, but we think those are manageable,” she said. “What we want to use this opportunity to do is to really begin thinking about how do you correct some of the missed opportunities of the past as you design your community to live with water.”

For Norfolk, the power of data goes well beyond floodwater management and emergency response. The city can use data to flag problem landlords, who own different properties under different names but can’t fool the Palantir platform’s ability to pull similar names and addresses, which are turned over to the city’s neighborhood specialists for further investigation.

One-pagers are kept on each of Norfolk’s 131 civic leagues, listing the five most common service requests per area.

Palantir is working with city departments on special projects, too, Frank said. Currently, 40 to 50 employees across eight departments have trained to use the data platform.

The beautiful-yet-overly-hardscaped city of almost 250,000 residents and 144 miles of coastline must return to its roots, Morris said, using natural systems to manage water and improve its quality along with that of the air and residents’ lives. Citizens, themselves, must take responsibility at the parcel level that they’re part of the flood-mitigation strategy and strive to reduce the impacts of higher water.

Traditional water-management thinking would have Norfolk wall itself off from floodwaters. Now, instead of eliminating them, Fugro is coming up with ways to retain them as water drains through the watershed.

Why? Heavy rainfall coupled with high tides, can create trouble for the city because stormwater can’t easily drain away. Higher tides create higher water levels in the Elizabeth River and coastal inlets, which in turn flood low-lying areas like Tidewater Gardens.

But the use of berms, bioswales, channels, retention ponds and other natural and grey infrastructure features are all options being considered to help water drain away more strategically.

Norfolk is currently an entrant in the HUD Exchange’s National Disaster Resilience Competition and hopes to use up to $500 million in winnings to, in part, revitalize flood-vulnerable areas like Tidewater Gardens.

Overall, the process for thinking about the different ways to embrace resilient planning also creates opportunities for cross-sector collaboration and community dialogue about what Norfolk’s future looks like.

With more innovative water-management infrastructure will come more bikeable spaces, the daylighting of buried waterways and opportunities to reconnect cut-off communities by using meandering waterside paths as a subtle way to say “walk this way,” Morris said.

At the same time, Norfolk, like many other U.S. cities, is thinking about ways to fix some of its earlier urban planning mistakes, like the construction of major highways that tore the heart out of certain neighborhoods and created huge barriers between neighboring areas. There may be opportunities to address those issues while adapting to higher water levels at the same time.

“In midsize cities, a lot of the time, some of the construction that we’ve done and the way that we’ve used the car has said, ‘Don’t bother coming across this street,’” Morris said. “What it does is it really breaks economic activity, breaks social cohesion, it breaks connectivity, it breaks mobility, and so it’s really important that as we think about how we’re going to manage water, we think about how we want to use the water.”

NEXT STORY: The Allure of ISIS Has Reached Long-Stable Ghana