Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir, 3rd left, arrives at the airport ahead of meetings with South Sudan's President Salva Kiir, in the capital Juba, South Sudan Monday, Jan. 6, 2014. Ali Ngethi/AP

Here's How Easily a Wanted War Criminal Can Travel the Globe

Sudan's pledges of support against enemies of the West and Saudi Arabia have greased the skids for alleged war criminal and President Omar al-Bashir's 21-country world tour.

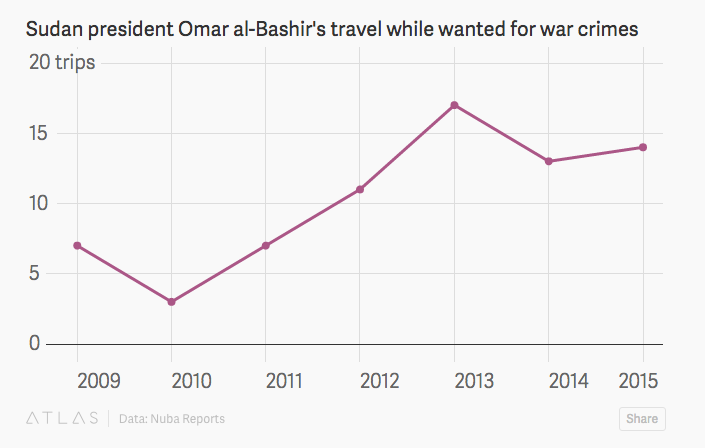

President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan has clocked in thousands of miles flying across the world since 2009, despite being a wanted war criminal.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) issued a warrant for al-Bashir’s arrest seven years ago today (Mar. 4) for his role in the Darfur genocide, accusing him of overseeing murder, extermination, forcible transfer, rape, and torture, as well as directing pillaging and other attacks against civilians. The warrant has not stopped the dictator—one of the longest serving in the world—from traveling 74 times to 21 countries since then, seemingly without fear of prosecution. Few countries, including the seven he visited that are signatories to the ICC, harbor the political will to arrest him, despite the ICC urging all states to cooperate fully with the warrant for his arrest.

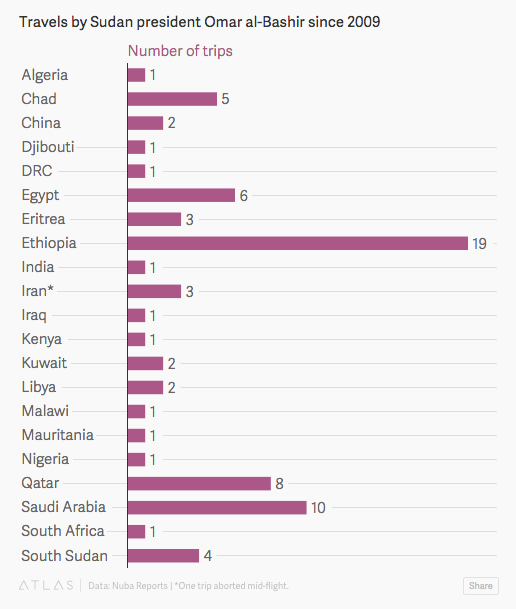

Bashir made his most recent trip abroad on Feb. 20, for the African Investment Forum (AIF) in Egypt, where Sudan, Egypt, and Ethiopia agreed to strengthen ties . It is his sixth trip since 2009 to the country, a signatory of the ICC that refuses to execute the warrant.

Bashir does not just continue to travel widely. He also continues to fight wars in Sudan that observers say use tactics that amount to war crimes. Since the warrant was issued, violence has spiked in Darfur, a war and civilian bombing campaign was launched in Blue Nile and South Kordofan, protesters have been killed, and Khartoum continues to be accused of supporting the rebels in South Sudan.

Related: A Conversation With an Accused War Criminal With Arms To Sell

After the warrant was issued, it was almost impossible for Bashir to travel. He was forced to cancel or cut short several trips as a result of international pressure or internal protests by civil society groups in countries that supported the ICC’s action. The latest diplomatic incident occurred when Bashir was able to visit South Africa without incident despite local protests and a court order that he be prevented from leaving the country until a decision was reached on whether to enforce the ICC arrest warrant. See more details of his trips on Nuba Reports’ interactive map .

A variety of bodies and governments have been complicit in allowing al-Bashir to dramatically increase the frequency of his trips in recent years.

The African Union has protected Bashir from arrest since day one. In 2009, the AU signed a declaration expressing concern over Bashir’s indictment derailing the Darfur peace process and another in 2010 stating the AU would not enforce the warrant against Bashir. By 2015, the AU called on the UN Security Council to suspend proceedings against the Sudanese president, urging them to withdraw the ICC referral. The AU has repeatedly accused the court of an unfair bias towards Africa since all current cases involve African countries. This argument ignores the fact that local prosecutors initiated all the cases except for Sudan and Libya.

Close alliances and foreign support from the Middle East has also eased travel restrictions. Saudi Arabia’s Sudan investments outdo all others with an estimated $11 billion in January and another $5 billion in military assistance one month later. A cash-strapped Bashir is all too happy to send troops to Yemen and possibly Syria for Saudi Arabia, expanding Sudan’s military ventures beyond the two internal conflicts .

Despite expressing concern over the conflicts in Darfur and Nuba Mountains, the European Union has provided Sudan €100 Million ($109 Million) to ostensibly curb migration and terrorism, according to a statement issued last month. These same issues have helped warm Sudan relations with the United States, Sudan’s foreign minister Ibrahim Ghandour said . Public claims by Sudan’s spy chief Mohamed Atta to deploy militias on the border to prevent movements of Libyan-based ISIS forces is well received by the US State Department.

In turn, the State Department has softened its public stance towards Khartoum. Last year, the its terrorism report to Congress praised Sudan for its cooperation on countering terrorism, news reports said . A more recent statement claims the rebels instigated the latest violence in Darfur, countering news reports citing the opposite . Foreign relations have thawed so much that Sudan has even requested US help in influencing rebel factions to participate in state-run peace talks. Several armed groups and opposition parties have rejected the peace talks termed a “National Dialogue” for undue government-influence.

The ICC warrant has, on occasion, curbed Bashir’s travels. A planned trip to Indonesia in April last year was scrapped after several countries, albeit anonymously, refused the Sudanese president permission to fly over their airspace. Diplomatic pressure also blocked Bashir traveling to the 2013 United Nations General Assembly in New York City despite the fact the US is not signatory to the ICC.

While Bashir has not booked a flight to western countries yet, international supporters have turned a blind eye to his foreign travels vis-à-vis the ICC arrest warrant. Khartoum’s pledges of support against enemies of the West and Saudi Arabia, and a continental union that defends African leaders before its citizenry, have assured visa stamps continue to appear in the president’s passport.

NEXT STORY: Russian Subs Are Reheating a Cold War Chokepoint