Draft Director Curtis W. Tarr is shown spinning a plexiglass drum at the beginning of the fourth annual Selective Service lottery in Washington in this Feb. 2, 1972 file photo. AP Photo

The Future of the Draft

As another Memorial Day passes with service members still at war, readers debate the merits of reinstating the draft.

In the wake of another Memorial Day, when most Americans recognized their fallen veterans by staying home from the office, it’s worth taking a moment to consider a perennial question: Should the military draft return? Yes, argued Joseph Epstein in The Atlantic earlier this year. Epstein, a short story writer and former draftee who served in the Army from 1958 to 1960, opposes an all-volunteer force for several reasons: It’s unfair for a tiny percentage of Americans—less than one percent—to shoulder the burden of fighting wars; the American public isn’t knowledgable enough on foreign policy; the draft could rehabilitate young criminal offenders; and, most of all, a draft would contribute to the “melting pot” that makes America great.

The following passage from Epstein echoes one of the core themes in James Fallows’s latest Atlantic cover story, “ The Tragedy of the American Military ” (which readers debated at length here ):

A truly American military, inclusive of all social classes, might cause politicians and voters to be more selective in choosing which battles are worth fighting and at what expense. It would also have the significant effect of getting the majority of the country behind those wars in which we do engage.

Epstein’s essay sparked a spirited debate in the comments section. Here’s George Hoffman :

I served as a medical corpsman in Vietnam (31 May 1967 to 31 May 1968). So my years in the military were dramatically different from Mr. Epstein's service. Much of what I experienced was so horrific, having viewed the human face of war on the wounded grunts, wounded civilians and even a few wounded VC guerrillas. They were all victims of that tragic and unnecessary war.

Therefore I would never subject our young men and women to the draft, given that both the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq now rival the Vietnam War as foreign policy debacles. I think that if Mr. Epstein served in Vietnam he would be less willing to bring back the draft, especially if he saw and experienced what I did. That in no way denigrates his service to his country. But let’s to honest; he served as a clerk far from the killing fields. So he has a civilian mentality.

The mentality of civilians on the draft, though, has been overwhelmingly negative the past few decades:

In fact, according to a 2011 Pew survey , recent veterans oppose a draft even more than civilians do: “More than eight-in-ten post-9/11 veterans and 74% of the public say the U.S. should not return to the draft at this time.” Commenter julia_g couldn’t agree more:

As a mother of a teenage son, I find it supremely cynical that Mr. Epstein would suggest sending my son to war where he might be killed or maimed, based on his own recollections of having a good time in the military, far from any danger. Yes, living and training together with people from different walks of life has its merits. But what the author really has in mind is not an army but a glorified long-term summer camp.

McDruid is wary of the draft for many reasons:

Maybe two million people would be taken out of the work force—that's a big hit to the economy. We'd have to pay them too, because we can't have slave labor. So run up more government deficits or taxes as you run up the flag. Add in training costs, food, uniforms, ammunition, and you have a tidy sum that would be better spent educating them in useful matters.

And, perhaps the worst: If we have a bigger military, then we might be pressured to use it more. Why not send troops to Syria? We're paying for them anyway. We'd end up mired in more wars, not fewer.

Islamic State militants lead what are said to be Ethiopian Christians along a beach in Wilayat Barqa, in this still image from an undated video made available on a social media website on April 19, 2015. The video appeared to show militants shooting and beheading about 30 Ethiopian Christians in Libya. Reuters was not able to verify the authenticity of the video but the killings resemble past violence carried out by Islamic State, an ultra-hardline group which has expanded its reach from strongholds in Iraq and Syria to conflict-ridden Libya. (Social Media Website via Reuters TV)

Bubba Gump , on the other hand, sides with Epstein:

I spent 28.5 years total in either active service or the reserves. It never hurt me one bit and I met some interesting people along the way. There is something about the uniformed military service that you just can't take away from one who served. It let me travel the world and have lasting connections that are a bond that only service members know. It also showed me the gruesome effects of war and what it can do to people up close and personal. When you have a screaming 18 year old coming across the radio begging for help, you know you cannot let them down and will do whatever necessary to get them out of that jam.

It wouldn't hurt us to spread the wealth of those experiences around a bit. So I'd give the draft a thumbs up, but it should be equal and fair. No deferments for education and only medical disqualifications apply.

But Bobloblaw67 worries that, under a draft, “we would have 5 million people in the military.” (The armed services currently have about 1.4 million active personnel and 850,000 in reserve.) Bubba Gump clarifies his stance:

You draft by lottery and fill the slots you need. We currently only have 11 active divisions (with one being an integrated division). We need at least 13 minimum to do the current job. You don’t just put 5 million in the military at once.

One of the last lotteries took place on December 1, 1969, and this long, mundane, but macabre scene gives you an idea of what it was like to see your number come up:

Fallows famously wrote about his own experience with the draft lottery in the 1975 essay, “ What Did You Do in the Class War, Daddy? ” Commenter James Nutley asks Bubba Gump and other proponents of the draft:

Would it be good if your workplace was filled with snarky, malingering folk who never missed a chance to say they didn't want to be there and thought the whole organization was stupid or a crime? Would you really want to work there?

If you think military service is important, volunteer. If you aren't willing to volunteer, leave it alone.

Cougar90210 counters:

Would it be good if you lived in a nation populated by increasingly snarky, prejudiced, and self-centered people? Would you really want to live there?

One of the key messages in Mr. Epstein's piece is that the draft created a genuine "melting pot" experience for him and many others, that brought them together in some commonly shared experiences in service to the nation—common experiences that helped them understand and appreciate their fellow Americans from all backgrounds. Would it not be a good thing if our society could become a bit more tolerant?

A retort from Nutley:

I am skeptical that any attempt to make Americans mix across class boundaries can work. The majority will perceive it as an affront to their personal liberty, and only a handful will emulate Epstein and expand their horizons. A draft proposes that we shall make people do work they don't want to do and they will, in time, be glad we did this to them. But the author's anecdotal experience does not convince me that society will accept it.

To throw another anecdote into the “melting pot,” years ago on The Atlantic I posted an account of my father’s experience as a platoon leader in Vietnam:

When brought to the battalion's recon platoon, I made only one request of the commander. I asked to bring my rifle platoon's "point man" (the scout, the first-to-the-front when traveling in file). He had very keen senses, was an excellent shot, and was strong as an ox and walked like a cat [seen in top photo, left]. His reputation among soldiers was that of a "John Wayne." I believe he had probably saved my life more than once.

However, the very intense members of the recon platoon were convinced that they already had the best point man in the battalion. To my surprise, the point man of this predominately-Southern, white group of men was a 20-year-old black Cajun soldier with a very slight build, noticeably effeminate speech, and who even wore a gold ring in his left ear. “Cajun” [seen in both photos] was quite a contrast to the other men, to say the least, particularly compared to my new platoon sergeant [top photo, right]—a self-described “redneck” from Georgia who had already served 6 tours in Vietnam and was so conservative that he voted for the segregationist George Wallace in '68.

For a more contemporary look at tolerance on the battlefield, in 2008, when “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was three years from repeal, a poll found that 73 percent of soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan were comfortable serving with gays. But anAtlantic reader, via email, points to where progress is still needed:

I've also know a couple of guys who became better people through their military service, including one who had been in the KKK for a short time but learned how wrong that was through his service. But it’s also true that the discrimination embedded in our society can do much damage in the armed forces. I was born a transgender girl in 1944. It would have been dangerous to come out in my youth, and I didn’t. If I’d been drafted, I could have been beaten up repeatedly with no one held accountable, or given a dishonorable discharge.

The ban on transgender service members is still in place but starting to falter . At the forefront of that change is Kristin Beck, a former member of the elite Navy unit, SEAL Team Six:

Another pro-draft reader from the inbox:

We need national service. My father, who flew 34 harrowing (by definition) missions in the ball turret of a B-17, was virulently opposed to the Vietnam War and told my brother and me that he would not let us serve. As it turned out, I was just young enough to have missed draft registration, so it never became an issue.

But some years later, as Afghanistan was heating up, I sat in on a debate about military policy at my typically-liberal liberal arts college. The geology professor, of all people, made the simple and unarguable point that the military exists to defend the nation, not to be a social welfare or jobs program. When we allow a disenfranchised underclass to become cannon fodder so that the rest of us won’t have to, we are far too likely to become adventurous.

But is there much truth to such claims that an all-volunteer military disproportionately draws from the least privileged Americans? Not really, according to a 2011 report from the Congressional Budget Office:

The report says that while 91% of last year's recruits were high school graduates, only 80% of U.S. residents aged 18 to 24 have attained that level of education. And high school graduates, the military says, make better soldiers than dropouts. ...

Critics [such as Korean War veteran and Congressman Charles Rangel ] have claimed that minorities are over-represented in the all-volunteer military because they have fewer options in the civilian world. The CBO disputes that, saying that "members of the armed forces are racially and ethnically diverse." African Americans accounted for 13% of active-duty recruits in 2005, just under their 14% share of 17-to-49-year-olds in the overall U.S. population. And minorities are not being used as cannon fodder. "Data on fatalities indicate that minorities are not being killed [in Iraq and Afghanistan] at greater rates than their representation in the force," the study says.

Commenter hank_the_engineer thinks the draft would in fact increase racial and socioeconomic disparities:

I understand the appeal of conscription as a form of social engineering. And I shared Epstein’s view, until I joined the Army. Even in the easy days of the late 1980s, I would not have wanted to serve with a bunch of disgruntled conscripts. Besides being bad for the Army, conscription might even backfire as a social program. During Vietnam, the rich and influential figured out how to game the system, and it seems likely that they would game the system again today, grabbing the easy jobs for their kids. In fact, that perversion of the selective service system was one of the reasons for ending the draft.

James Blair is on the same page:

Even if the draft process itself were fair (which it never is), the politics and the privilege issues continue into military service. Even if the rich get drafted, they will get directed into roles where they aren’t at risk. Al Gore, for example, went to Vietnam, but of course when he got there it was decided that he should be a journalist.

Alex Kent , on the other hand, supports the draft because “young Americans and their parents might feel more impelled to learn about U.S. policy because they would have more of a stake in the country's direction.” An emailer is more specific:

Had the Bush administration activated the draft in 2002 when it became clear that we could not achieve our goals in Afghanistan if we also invaded Iraq with the all-volunteer force, the American people and their Congressional representatives would have asked a lot more questions about the necessity of the Iraq war and avoided the “chickenhawk nation” Fallows writes about.

Xenophon thinks a draft could bridge the partisan divide:

It would reinforce the idea that citizens of the U.S first, and then cultural identity second. The fragmentation of the political scene that we see today is fundamentally an effect of our society being sorted away from this idea, such as identifying as Republican or Democrat first, which leads to a bizarre sort of tribalism.

Another pro-draft argument comes from an emailer who spent 26 years in the Air Force:

The entire concept of war has gotten totally out of whack. If there is such a threat that our country must truly go to war, then the entire population must be personally involved. There must be a draft. I would even consider a rating one step higher than 1A that would be applied to the offspring of members of Congress. If this concept is not acceptable, then we simply should not go to war.

Douglas Dea doesn’t go that far:

Sure, there is a part of me that wants to see the sons and daughters of Congressmen, party heads and CEOs donning uniforms and marching through Baghdad. If these guys are so eager for war, let them put their own flesh and blood on the line.

But really, we shouldn't force them to; that’s just not right, despite how sweet and satisfying it may be. Frankly, it is immoral and un-American to force people into spending years of their lives doing something they don't want to do, and something that is also dangerous and potentially morally fraught. (Do you really want to force strongly religious people who are against killing to go out and kill? How many Amish and Mennonites do you want patrolling the streets of Kabul?)

There must be, and are, other ways to serve. How about drafting people to serve as park rangers or infrastructure repairmen? Or volunteering for the Peace Corps?

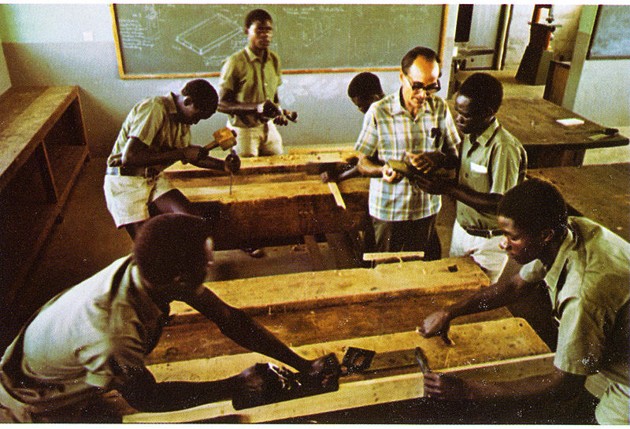

A Peace Corps industrial arts instructor teaches young men in Kenya carpentry skills in 1970. President John F. Kennedy had set up the Young American Peace Corps in 1961. (Wikimedia Commons)

Another advocate of non-military national service is an Atlantic emailer and veteran:

I grew up in one of the poorest places in America, on an Indian reservation in the West. Military service is central to the identity of the place and the people who live there. Most of the strong male role models of my upbringing, from my pastor to many of my teachers, were veterans. I graduated from high school in May of 2001 with asmall class of 87 people, and of those 87 people, 8 joined the service, about 9% in total.

A draft isn't a possibility—the legacies of the post-Vietnam army saw to that—and the professionalization of the military has created a cadre of NCOs and officers who are better trained than their Vietnam Era counterparts. But perhaps a vision of national service broadly conceived is something that we should be talking about as a nation. Requiring two to four years of voluntary service in multiple capacities, whether military or civilian, and in return guaranteeing a modicum of veterans benefits for the nation's youth would go a long way towards opening up the avenues of opportunity to the nation's disadvantaged.

One more emailer adds:

I feel that draftees should be made to spend a portion of their service rotating through the VA hospitals and clinics around the nation. Doing so will bring these young members of society face to face with the consequences of policy mistakes and hopefully make a vivid enough impression that as they move into positions of power makes them more mindful of the consequences of getting involved in wars without clearly defined objectives.

But Harry McNicholas warns that national service could attract exploitation:

You cannot expect a government to form some youth program without politics being involved. It’s like thinking a religious youth program will not involve religion.

I have never heard of anyone being forced to serve a charity. You cannot force people to be better people.

Lorenzo proposes another kind of national sacrifice:

If there was a national tax that automatically went into effect upon declaration of war, the American people will be able to decide if they really want to pay for it.

But disqusplaya shakes his head:

I pay my taxes. It's MORE than enough. And dedicating two years of my short life to some nebulous concept like "The Government" is a terrible terrible idea, borne of fascist thinking. The government serves us, not the other way around.

Your thoughts? Email hello@theatlantic.com and I’ll update the post with your best points. Update from a reader:

As civilians, we can do a lot for returning veterans. If there are vets in your area, I encourage you to find out what they need. To give one example, I've been tutoring an Afghanistan vet in pre-med subjects for a few years. We belong to the same rowing club, and we meet there once or twice a week at 5:30am to review math and physics. This kind of volunteering also can bridge the culture gap: I'm a preppy Jewish guy from a wealthy Boston suburb, while the vet I tutor is Pentecostal (I think) and hails from poor rural Florida.

It's a small thing, but if many people do small things, it can make a big difference.