Recruits line up for breakfast at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, in 2010. Kelley McCall/AP

The American Military Declares War on Sprawl

For the Pentagon, walkable, bikeable military installations are key to improving the health of troops.

Busy each day with thousands or tens of thousands of people, a military base is a mini-city. It has its own police, fire, and recreation departments, and even a “mayor” (the base commander). It has traffic, crime, and pollution, just like a regular city. And its residents are dealing with a major public health concern—obesity. Now the U.S. Department of Defense is looking to the environment of the base itself to get its forces into shape.

Every large employer these days seems to be pushing a health and wellness initiative. But the health of the million-plus workforce of the Pentagon is critical to national security: Troops who don’t meet a minimum fitness standard can’t fight. Treating illnesses associated with obesity and tobacco use costs the Pentagon $3 billion a year. More troops were evacuated from Iraq and Afghanistan because of serious sprains and fractures—which overweight and less fit people are prone to—than because of combat injuries.

“From a readiness perspective, our service members are supposed to be fit,” says Ed Miles, director of strategy and innovation for military community and family policy at the DoD. “But we’re just like everybody else. We lack time; we lack facilities.”

Changing the menus in mess halls has been one part of the DoD’s approach. Taking a cue from the active design movement, it is also scrutinizing the layouts of its bases, which may deter walking, cycling, and working out, and make it hard to find healthy food. In 2014, the Pentagon launched the Healthy Base Initiative to test physical improvements at 14 military installations. (Most are in the U.S. and most are bases, but a few are posts or agency headquarters.) Because military planning happens very slowly, the DoD prioritized quick micro-changes, such as signs encouraging people to take the stairs, family fitness centers that provide child care while adults exercise, and farmers’ markets.

“Our installations were built for the automobile,” Miles says. “They weren’t built for walking, for biking.” Since they have the same problems as many civilian towns and neighborhoods but are relatively self-contained and self-governing, they’re good places to trial environmental fixes.

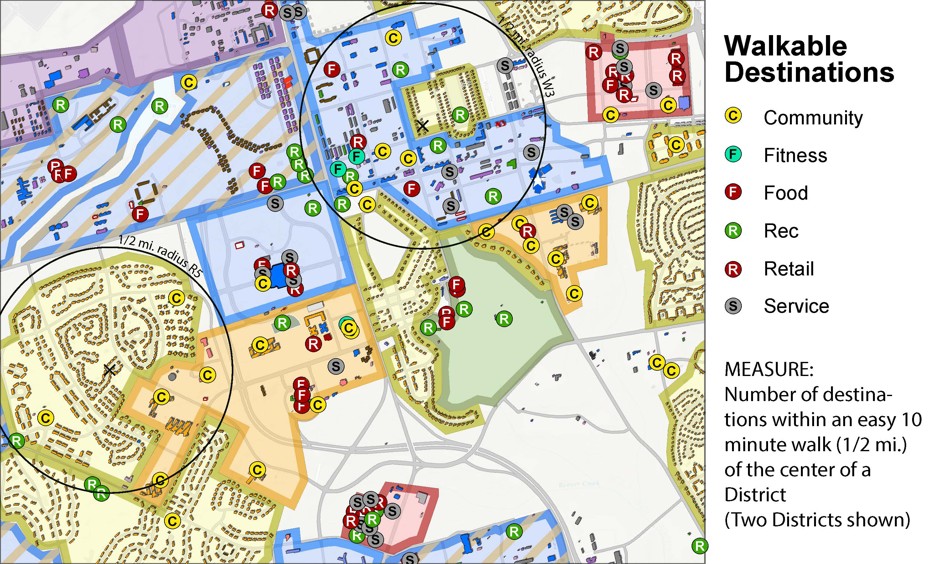

Two districts are analyzed on this map. The housing area, in the lower left, has few destinations and only two types of them. The mixed-use district, in the upper right, has many destinations of all types. Occupants of this district were found to be much more likely to walk or bicycle to fulfill their daily needs and to get 30 minutes of physical activity each day. (Courtesy of Arrowstreet)

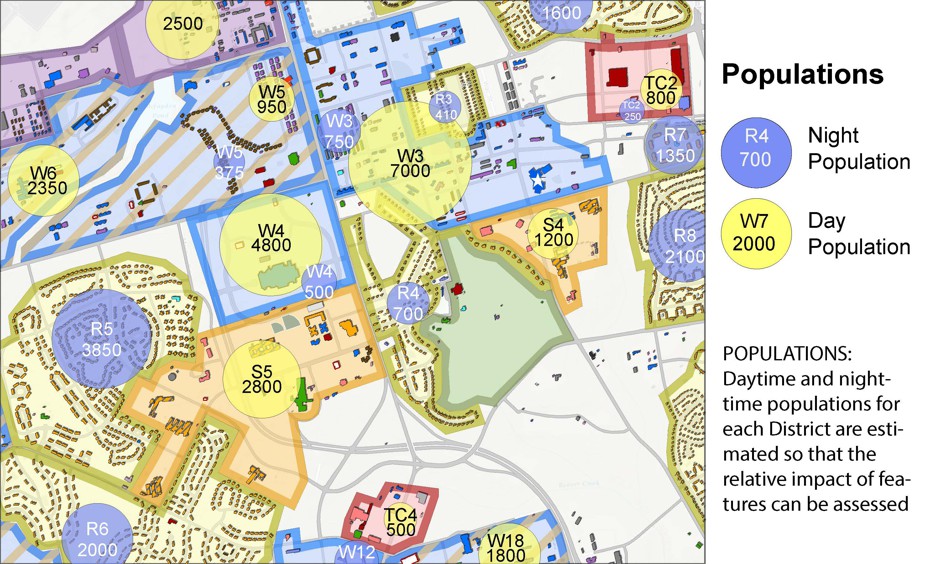

The designers used GIS software to calculate approximate numbers for daytime/on-duty and nighttime/off-duty populations in different areas of the base. (Courtesy of Arrowstreet)

DoD worked with the Boston architecture and planning firm Arrowstreet and a dozen-plus other outside experts. The architects did a physical assessment of nine of the 14 installations in the study, creating GIS maps to determine how everything connected on base to affect the quality of life. Could service members walk from one place to another instead of getting in their cars? Could their kids walk to school safely? Could people easily get to a fitness center at the end of their shift, and find a healthy meal on their break?

Often, says Arrowstreet principal Patricia Cornelison, food services were clustered together in one place, rather than distributed “in some way that is a little more sensitive to where people are.” The 24-hour nature of life on base added another dimension to the analysis, says her colleague Scott Pollack. “Not only did we have to understand where the stuff was—the fitness, the food—we had to map where people were, and where people were temporally,” Pollack says. “One of the hurdles was that stuff wasn’t where they were when they needed it.”

The size of the installations ranged from small (the 3.5-square-mile Naval Submarine Base New London in Groton, Connecticut) to extremely large (the 27-square-mile, 140,000-population Fort Bragg in North Carolina). Some were in remote locations while others were embedded within urban areas. Nevertheless, the architects and other study collaborators were able to draw several general lessons.

First, as the mammoth Healthy Base Initiative report notes, the built environment has a crucial role to play in supporting people’s health on-base: “[T]he factors that play a role in active living are complex and many-layered. Thus, simply promoting physical activity will not, by itself, result in needed changes—the built environment needs to be addressed as well.”

Central hubs can allow as many people as possible to eat, work out, shop, and go to the doctor without having to drive. In more out-of-the-way spots, though, food trucks with nutritious options could make it convenient to get a healthy bite to eat, the report says.

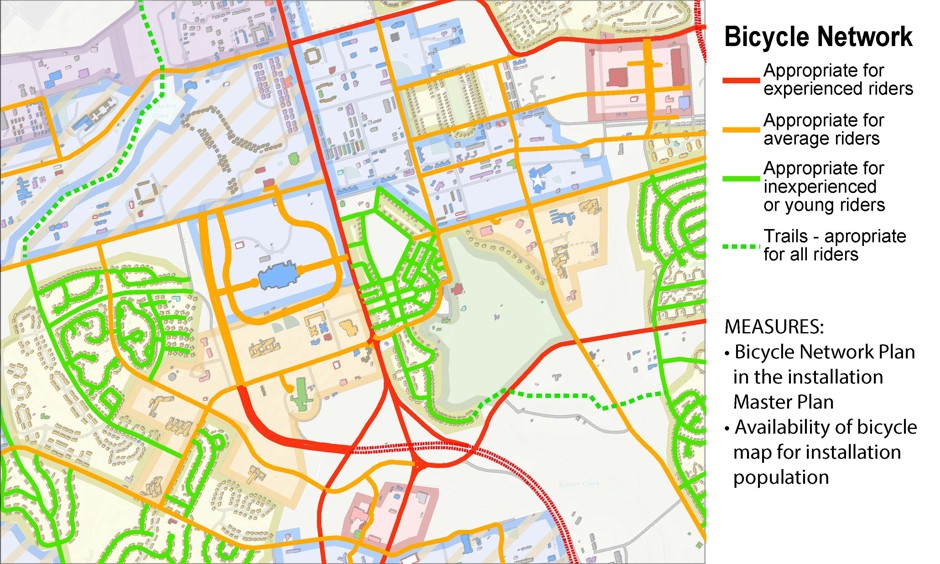

The m-PAC assessment of installations, developed by Arrowstreet from a tool first used in Michigan (the acronym stands for “the military promoting active communities”), measures whether an installation has created a pedestrian and bicycle master plan, how much of that infrastructure is in place, and whether there is a bicycle map available to the general public. (Courtesy of Arrowstreet)

During the study, the Defense Logistics Agency at Virginia’s Fort Belvoir piloted a bike-share program, paying for it out of the commander’s discretionary funds. “Guys were lined up at lunch for the bikes,” says Miles, and the program is still running. But Fort Belvoir was the only base to try it because of funding limitations and concerns about partnering with a private company. The report urges DoD to consider public-private partnerships or replicate the university-campus bike-share model, where multiple departments contribute to the cost.

Service members’ use of fitness facilities often hinged on child care, the report authors found. If the drop-in child-care center filled up or was too far from the gym, parents weren’t able to exercise. The report suggests grouping child care, fitness centers, and schools in future development. (That seems like an idea worth trying off-base, too.)

Arrowstreet’s designers developed a rating tool that commanders can use, scoring their base on how well it supports active living through features like sidewalks, bike lanes, and commercial centers. But decisions to improve military infrastructure require money and a lot of time. “Whenever you’ve got to build something on a military installation, things like that are in the planning process for years. I mean, years,” Miles says. Every base has a long-term planning guide and a board that approves projects, contingent on funding.

That can lead to skepticism about the ability to really make an impact. In the field, “we didn’t see a lot of holistic support in terms of the built environment,” Miles admits. “They couldn’t change it. It takes time.”

Making bases better doesn’t have to cost a lot, though. The report recommends diverting some funding for parking and roads toward sidewalks and trails, which are much cheaper. “We’re hoping folks that read the report will take that into consideration when they’re looking at their improvement plans over the next five to ten years,” Miles says. Even a few bases that installed better sidewalks or debuted all-in-one fitness and child care centers could reap real benefits and serve as models for others to follow—not least the sprawling office parks and subdivisions of the civilian world.