U.S. Army soldiers board a U.S. Air Force C-17 Globemaster III from the 816th Expeditionary Airlift Squadron for transport while the aircraft and its crew conduct combat airlift operations for U.S. and coalition forces in Iraq and Syria, Nov. 11, 2017. U.S. Air Force Photo by Tech. Sgt. Gregory Brook

Why Withdrawing from Syria and Afghanistan Won’t Save Much Money

The president’s desired troop drawdowns aren’t even penny-wise, and they’re probably pound-foolish.

Citing war-weariness and a desire to save money, President Trump has repeatedly stated his intent to pull American forces out of Syria and Afghanistan. Critics—including the Senate GOP—have largely argued that these withdrawals would be premature as long as the Islamic State remains viable and negotiations with the Taliban continue. (The Pentagon’s own internal watchdog, citing operational commanders, warned that the Islamic State “could likely resurge in Syria within six to 12 months” absent sustained counterterrorism pressure.) The opportunity cost of ending these missions with important objectives so close at hand, they say, is high. Yet even from a strictly financial standpoint, these withdrawals make no sense.

President Trump has said he wants to remove roughly 1,600 U.S. advisers from Syria and about 7,000 American advisers from Afghanistan. He envisions shifting the former to existing bases in Iraq, leaving a total of 400 troops at two Syrian locations. In Afghanistan, the initial plan will bring home up to half of the 14,000 U.S. troops over the next year or so, leaving counterterrorism units to continue fighting the Taliban and the Islamic State. Overall, Trump’s proposed dual withdrawal will essentially return U.S. posture in Iraq and Afghanistan to what it was in the late Obama years, with a significant residual capability to continue monitoring and responding to emerging terrorist threats.

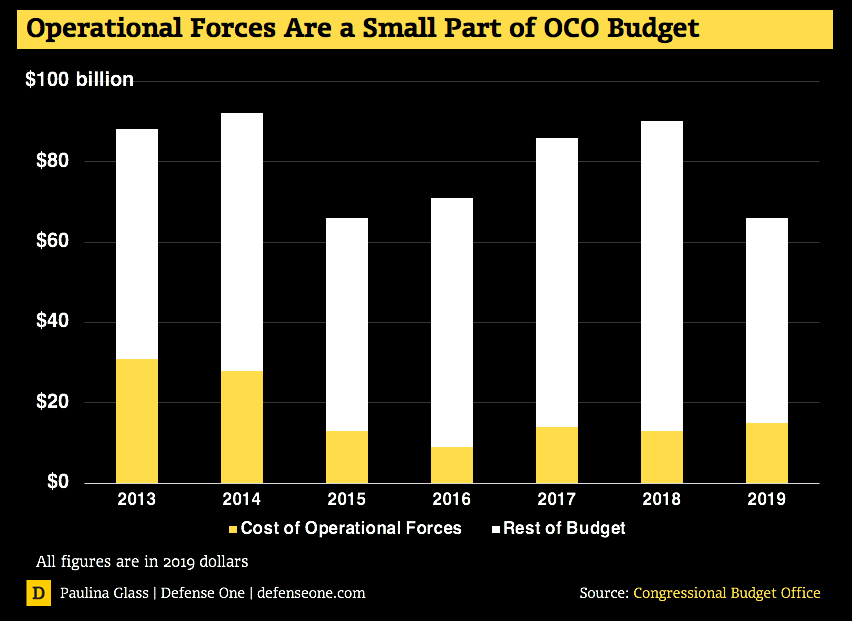

While withdrawing around 9,000 troops sounds like a slam-dunk way to trim the military’s current $69 billion war budget, these specific plans won’t save much at all because that “significant residual capability” is the most expensive part of the fighting effort. The war budget is relatively insensitive to small changes in troop levels and operational tempo, a phenomenon observed by budget analyst Todd Harrison during the Obama administration.

Related: Pentagon Wins a Reprieve with Trump Approval of ‘Residual’ Forces in Syria

Related: What Lies Beyond America’s Deadliest Day in Syria

Related: Army Chief Confirms US Will Hand off ISIS Fight in Syria

First, the proposed plans do not affect the fixed costs of simply having a presence in Iraq and Afghanistan. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office recently dissected the military’s current war budget and found that about $47 billion of the $69 billion—or 68 percent—pays for fixed and/or enduring costs in war zones. In essence, whether there’s 7,000 or 14,000 operational troops in Afghanistan, they need about the same amount of basing, security, communications facilities, and intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance missions. No matter the number of airstrikes, the military needs wide-ranging infrastructure to conduct any airstrikes in Iraq, Syria, or Afghanistan. Calculating the cost is a bit like hosting a massive party in a very remote destination—once you decide to throw the party and bring 300 people, adding another 300 is cheap by comparison. Your DJ and band cost the same no matter the crowd size, and the planes ferrying your food and drink are coming on expensive flights whether you order one case of champagne or ten.

Second, the particular troops—advisers—the president wants to withdraw are the cheapest to deploy. While their advise-and-assist mission remains the core of American efforts in Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq, a lot of the funding for that mission is sent directly to the forces from host nations. By comparison, the troops used for counterterrorism missions require a vast infrastructure to enable their dangerous missions, including airlift, air support, search and rescue assets, and expansive airborne intelligence work.

Taken together, the fixed costs of being in Iraq and Afghanistan combined with the low per-unit costs of the advisers being withdrawn means the savings will likely be in the low single-digit billions out of a $69 billion war budget.

Lastly, these withdrawals could actually cost money. First, commanders in the field will almost surely request additional airborne intelligence missions to offset the loss of old-fashioned intelligence collection on the ground, particularly in Syria. Second, the Pentagon may increase the tempo of airstrikes to make up for the anticipated loss of combat power when host-nation forces no longer receive U.S. advice and assistance. Third, leaving Syria requires a plan to deal with more than 1,100 Islamic State detainees currently held by Syrian Democratic Forces. This could result in additional expenditures at Guantanamo Bay or new U.S.-funded efforts to hold and process these detainees elsewhere. Fourth, given the current state of play in both Syria and Afghanistan, the timing of the withdrawals could upend promising developments and require the deployment of even more forces in the future.

At day’s end, the president will pull troops out based on a number of calculations—a supposedly war-weary public, lack of conclusive wins, and frustrations with partner nations. But the one thing he won’t be able to credibly say is that these minor withdrawals will save much money.