Villagers wade into floods caused by heavy rains in Liangdu township on October 11, 2021, in the Shanxi Province of China. China News Service via Getty Images / Zhang Yun

As Climate Change Threatens China, PLA Is Missing in Action

China’s military will have to reckon with a new security environment. When will it start?

As climate change forces the world’s militaries to adapt to new security conditions and ponder their own carbon footprints, the People’s Liberation Army has been largely silent.

The same is not true for the Chinese government as a whole; Xi Jinping, for example, has promised to reduce the country’s carbon output starting in 2030 and achieve full carbon neutrality by 2060. But little has been heard from the PLA’s senior leaders, academics, and strategists. While climate change is a part of the Chinese military and militia’s concept of non-traditional security threats, addressing its effects does not yet appear to be part of its security strategy.

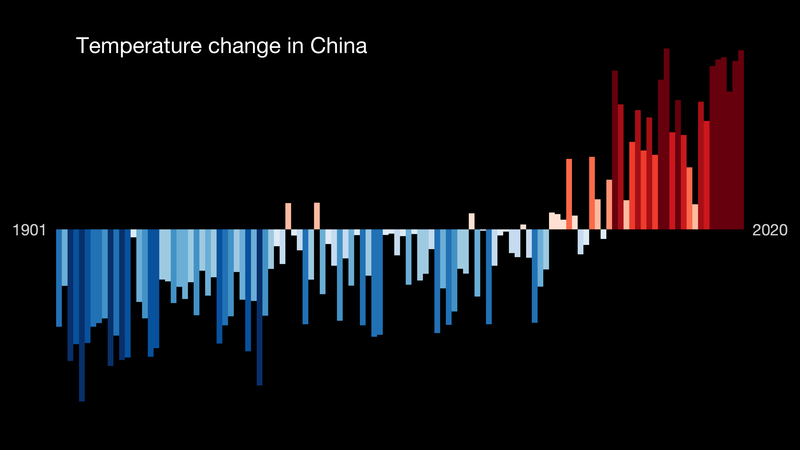

The PLA’s silence is not due to China being somehow insulated from climate change. The country’s average annual temperature rise rate has been nearly double that of the global average, with the past 20 years having been the warmest in China since 1900, and 2020 the warmest year yet, according to the China Meteorological Administration Climate Change Center’s August 2021 Blue Book. The Blue Book further reported that China saw a marked increase in “extreme precipitation events” in the last 80 years, while at the same time seeing a decrease in the annual number of rainy days. Put another way, China is not seeing the rainfall it once did, and when it does rain, the effects tend to be destructive rather than beneficial.

Source: Ed Hawkins, University of Reading

These drastic changes present a range of security problems for the regime, and demands on the PLA. The expected uptick in extreme storms played out in Henan’s capital of Zhengzhou in late July. In just three days, a torrential downpour dumped an ordinary year’s worth of rain on the region, displacing 200,000 and directly affecting some 3 million more. More than 5,000 troops were sent to restore order, repair dams, and clear debris.

Meanwhile, other areas are getting less rainfall, adding to economic and social pressures and tensions within an authoritarian state. Hydroelectric reservoirs are drying up, reducing the electrical power available to deal with hotter summers. During last May’s heat wave, Guangdong ordered factories to shut down lest the power grid collapse. As sources of fresh water decline—the Yellow River is reportedly down 90 percent since 1940—sub-standard sources may be tapped for use in homes. But up to 80% of China’s groundwater is estimated to be contaminated by toxic materials. In an era when annual environmental petitions to the Chinese government rose from 1.05 million in 2011 to 1.77 million in 2015, declining access to clean water could provoke unrest.

Few countries stand to lose as much as the world’s ice melts and its oceans rise. By some estimates, China accounts for more than 30 percent of the global exposure to extreme coastal water level rise. It has more than 11,185 miles of coastline and more than 6,700 islands. Its major urban economic centers are mostly located along its Eastern coast and the river valleys that flow into it. Studies suggest that rising seas will displace at least 30 million people in China by 2050.

Rising seas will also displace PLA facilities and forces. Hainan and Jiangsu coastal bases have already experienced the fastest sea level rise compared with other locations, according to a report from China’s Ministry of Natural Resources. Other coastal provinces such as Guangdong, Zhejiang, Guangxi, and Shandong are also experiencing higher-than-average sea level rises. The multiple PLA facilities on China’s natural and manmade islands in the South China Sea are at increasing risk from the kind of damage that Typhoon Rai caused to the Vietnamese-controlled island of Southwest Cay and the Philippine Coast Guard station on Thitu Island.

While the PLA does seem to consider energy security important, consideration of the full spectrum of climate threats is still lacking by comparison. The PLA established a committee of climate experts 13 years ago, but it does not appear to be active. Climate change went unmentioned in the PLA’s 2019 Defense White Paper. Nor does the PLA appear to be taking the ever-increasing threats of environmental catastrophe seriously as part of their training or strategic outlook. There has been no public discussion of exercises or attempts to wargame the effects of climate change on China’s security environment. Nor does construction appear to be slowing down on island installations in the South China Sea, despite the fact that many will find themselves underwater when the ice caps melt.

All this contrasts with many other militaries in the region and beyond. Australia’s military, for instance, began to address the issue more than a decade ago, in its 2009 White Paper. In the United States, climate-related events have been part of wargames since 2016. Last January, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said climate change had already directly affected 79 DOD installations in every geographic command, adding that flooding, drought, wildfires, and extreme weather events have affected military installations at home. The department’s 2021 Climate Adaptation Plan calls for building installation resilience and climate-informed decision-making, and the forthcoming National Defense Strategy is expected to include climate risk assessments.

The changing climate will eventually force China’s military to reckon with a new security environment. As Trotsky might have said, the PLA may not be interested in climate change, but climate change is definitely interested in it.

Thomas Corbett is a research analyst with BluePath Labs. His areas of focus include Chinese foreign relations, emerging technology, and international economics.