The San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock Fort Lauderdale (LPD 28) during sea trials in 2021. Huntington Ingalls Industries

Ending Production of This Warship Is a Mistake

The Navy’s new shipbuilding plan would replace all but three more LPD-17s with a vague plan to get started on a replacement class.

Observers have rightly criticized the recent release of the “Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2023” (“annual” of late more honored in the breach than the observance) for its insufficiency and inconsistency with the requirements of great power competition. This essay focuses on the unfortunate decision to truncate the LPD-17 Flight II production line, a topic treated in greater analytical detail in the May 4 release from the Congressional Research Service authored by the indispensable Ronald O’Rourke.

Amphibious ships are the most obvious manifestation of the historic and symbiotic operational relationship between the Navy and the Marine Corps. Amphibious ready groups, or ARGs, typically consisting of three ships (a dock landing ship, or LSD; an amphibious transport dock, or LPD; and an amphibious assault ship, or LHD/LHA) serve as a critical component of the Department of the Navy’s forward-deployed conventional deterrence and crisis response capability. Embarked on these ships are about 2,200 combat Marines ready to move ashore with aviation, artillery, light armor, and infantry capabilities. This powerful marriage of the benefits of sea-maneuver and power-projection ashore provides combatant commanders with options for deterrence of aggression and assurance of friends and allies, not to mention the oft-used capability to provide humanitarian assistance in response to natural disasters.

Shipbuilding plans like the one recently released are a means to inform Congress and industry of the Navy’s plans to buy and build ships specified in its occasional force structure assessments, the latest edition of which was released in 2016. That assessment called for a total force of 38 amphibious ships (up from today’s 32) including 12 LHD/LHAs, 13 LPDs, and 13 LSDs, which were to be replaced, one for one, by a variant of the LPD 17 class. It is this variant—the LPD 17 Flight II—that is truncated in the latest shipbuilding plan, resulting not in 13 as was called for in 2016, but only three.

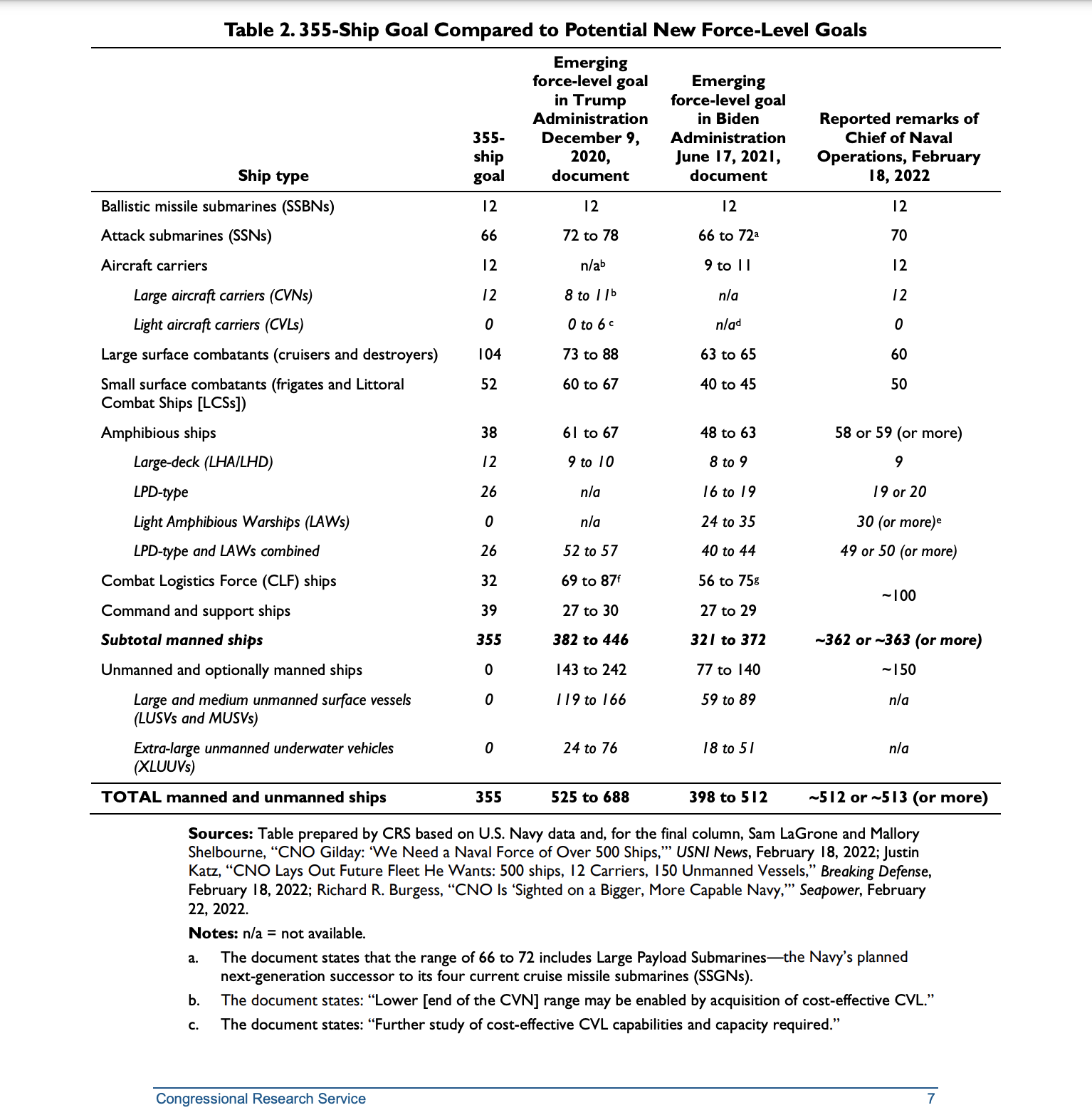

The Navy has done work on new force structure projections, which are summarized by a table in the Congressional Research Service’s latest update of its own force-structure report:

Notable is the 2020 addition of the Light Amphibious Warship, or LAW, a new class of vessel sought by the Marine Corps as a key enabler of its Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations concept. Planned at somewhere between 200 and 400 feet in length and 3,000 to 4,000 tons, the LAW will perform different missions than existing amphibious ships. Equally worthy of attention is the drop in the “LPD-type” line from 26 in the 355-ship goal to “16-19” in the Biden administration’s 2021 document. When synthesized with the 2023 shipbuilding plan—the one released in April that ends LPD 17 Flight II production after three ships—it appears that the Navy plans to harvest LPD force structure (and large-deck amphibious assault ships) at least in part to pay for the LAW. Movement in this direction is unwise.

First, to the extent that the 38-ship amphibious requirement laid out in the 2016 force-structure assessment has relevance, it is difficult to reconcile the decline in numbers—both actual and planned—with six years of Chinese navy buildup and intensifying Chinese government rhetoric. Put another way, the world has gotten more dangerous, not less, bringing into question downward movement in traditional amphibious ship numbers.

Second, today’s amphibious force of 32 ships is inadequate to the missions required of it, as was demonstrated recently by the testimony of Lt. Gen. Karsten Heckl, commanding general of Marine Corps Combat Development Command and deputy commandant for combat development and integration. Speaking on April 26 before the Senate Armed Service Committee, Heckl verified that an ARG and its associated Marine Expeditionary Unit were unable to respond to urgent tasking requested by NATO Supreme Commander (and U.S. European Commander) Gen. Tod Wolters to beef up forces in the face of then-gathering evidence of Russian aggression toward Ukraine. Maintenance problems precluded the assigned amphibious ships from being able to meet the emergent tasking, and other, ready ships were not available to pick up the slack. This lack of excess capacity to meet operational requirements suggests that a force of fewer ships is subject to additional risk.

Third, there is a troubling category error emerging, one in which budgeteers consider LAWs and larger L-class ships interchangeably. In the table reproduced earlier, the Navy segregates LAW and other amphibious ships, but in the latest 30-year shipbuilding plan, it makes no distinction, with the category “Amphibious Ships” containing LHA/LHD/LPD and LAW. This distinction is important, as noted recently by Rep. Rob Wittman, R-Va., ranking member of the House Armed Services’ seapower and projection forces subcommittee: “I think we need to build both. You need LPD. You need to do advanced procurement on LPD-33, now. Get that done,” Wittman said at the Navy League’s Sea-Air-Space Symposium in April. “Remember, the LAWs” are “different than a largelift vessel. It is not an LPD. These are intra-theater connectors and what the Marines are going to need to move around.”

Wittman’s reference to LAW as a “connector” is appropriate, and it speaks to the chasm of capability that exists between an LPD and a LAW. They do vastly different things, and they are quite different ships. (The LPD weighs in at 25,000 tons, at least six times the LAW’s envisioned displacement.) The suggestion in shipbuilding plans that one can be cannibalized to create the other ignores both the operational requirements of the numbered fleets and the great distances from U.S. home ports where those operations occur.

Fourth, the DoD fascination with warfighting above war-prevention (rather than a mix of both) improperly discounts large amphibious ships. Analysts fixating on the vulnerability of large amphibs fail to consider two facts. First, virtually everything on the modern battlefield is vulnerable, and second, the Navy spends the overwhelming preponderance of its time deterring war and responding to crisis, something that the LPD is better at than most alternatives. Vulnerability is reduced through both operational habits and capable countermeasures, while “being there” with enormous capacity is key to an effective conventional deterrent.

Finally, ending the LPD 17 Flight II production line makes little sense for an already strained shipbuilding industrial base. While the shipbuilding plan ends the LPD line with a ship purchased in fiscal 2023, it is doing so with no understanding of “what comes next?”—only a vague statement that the Navy will begin studies on a next-generation amphibious ship that year. Even under the most accelerated of conditions, the time from studies to commissioning of a ship the size and complexity of an LPD will occupy a decade. In that time, the decline in shipyard workload will drive skilled artisans into other opportunities and further exacerbate the well-understood labor crisis in the shipbuilding industry.

What should the Navy do? First, it should continue to argue for the resources it needs to build and maintain a fleet that is up to the challenges of renewed great power competition, and it should no longer entertain false choices between categorically unlike alternatives. Second, Congress should make it clear that predictability in shipbuilding will be maintained, and that until the Navy has a replacement program for the LPD, a new one will be acquired every two years (and that it is in the Navy’s interest to program for it rather than having Congress do it for them). Finally, the Navy must cease to view the L-class ships as “the Marine Corps’ Navy,” and reclaim them as proper warships. Existing LPDs should be backfit with capable surface-to-surface missiles and even land-attack weapons, with new LPDs fielding them in new construction. A Navy/Marine Corps team with sufficient, lethal amphibious lift along with efficient intra-theater connectors is a force that provides potential adversaries with operational dilemmas, something no effective conventional deterrence strategy can do without.

Bryan McGrath is the Managing Director of The FerryBridge Group LLC, a consultancy with clients in government and industry. His public writing—including this essay—represents what he thinks, not what his clients think.

NEXT STORY: Stop Making a Big Deal of NATO’s Next Members