The Iran Nuclear Deal, in 3 Charts

Thursday's framework agreement was a start, but there are hundreds of areas where a final deal could be derailed.

To assess the impact of the accord that the United States and its partners reached with Iran on Thursday, it is useful to start with five bottom lines. To what questions are 15,000, 12,000, 10, 5, and 0 the answers?

- 15,000 is the number of pounds of low-enriched uranium that would be neutralized.

- 12,000 is the number of centrifuges that would be decommissioned.

- 10 is the number of months by which Iran’s “breakout” timeline to a bomb would be extended.

- 5 is the number of bombs’ worth of low-enriched uranium that would be neutralized.

- 0 is the number of bombs’ worth of plutonium that Iran would be able to produce.

Of course, the framework accord still has to be translated into a more specific, binding agreement. And even more important, assuming that is done, the agreement has to be implemented. But if this happens, a state that currently has seven bombs’ worth of enriched uranium and 19,000 centrifuges, and is six weeks away from breaking out to produce the core of a bomb, will have been pushed back materially on each of these fronts. Moreover, the route to a bomb using plutonium rather than uranium, which Iran has pursued for over a decade at its Arak facility, will have been abandoned.

For more specific details, see the three tables below from Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. The tables summarize the new framework accord and analyze differences between where Iran stood before negotiations began and where it will be if and when this accord becomes reality.

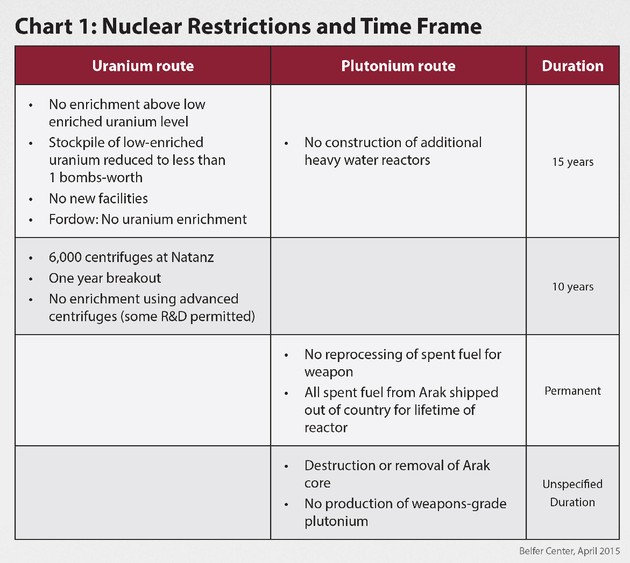

Chart 1 simplifies the constraints that the accord places on Iran’s uranium route to a bomb, its plutonium route to a bomb, and the number of years Iran has agreed to observe the constraints.

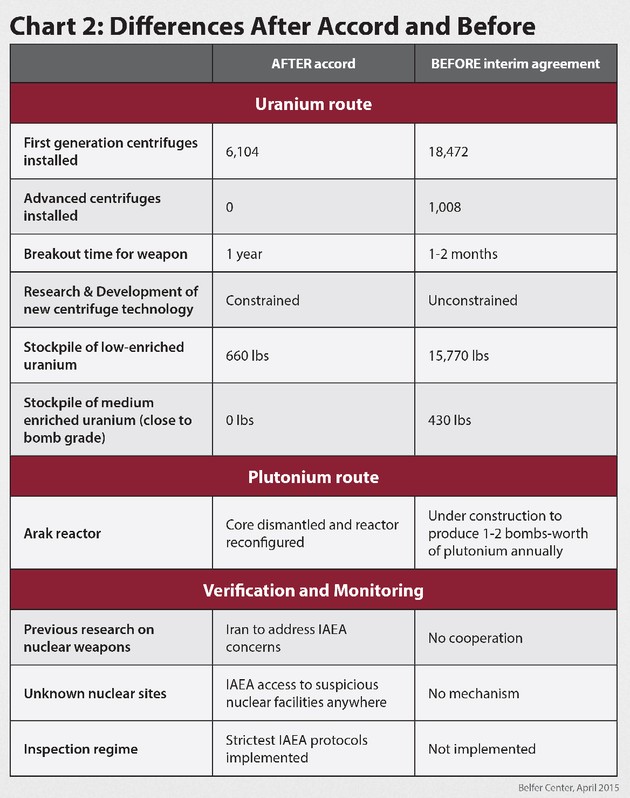

Chart 2 compares Iran’s nuclear capability after the accord is implemented with its program before the interim agreement.

Chart 3 tracks the installation of centrifuges at Iran’s nuclear facilities, and illustrates how the accord would reduce Iran’s centrifuge count.

By eliminating 12,000 centrifuges and five bombs’ worth of low-enriched uranium, the accord extends the breakout timeline for Iran to produce the highly enriched uranium core of a bomb to one year. By requiring the reconfiguration of Iran’s planned plutonium-producing reactor at Arak, the accord essentially closes this door to a bomb. And by agreeing to establish a new mechanism that will allow unprecedented access for the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to suspicious nuclear sites anywhere in Iran, the accord makes it much more difficult for Iran to cheat.

Between this framework accord and a final agreement lie many difficult negotiations. On literally hundreds of specific items, there are countless devils in the details. From my personal analysis of the challenge posed by Iran’s nuclear ambitions, many of these details matter more than the announced constraints on Iran’s enrichment activity at its declared facilities. Most important for me will be requirements for transparency and verification that maximize the likelihood that if Iran attempts to develop nuclear weapons at a covert facility, intelligence communities in the United States and other nations will discover that fact before Iran reaches its goals.

In sum, the Obama administration and its indefatigable secretary of state deserve a hearty round of applause for what has been achieved at this point. What remains to be done will be even more difficult, and in the longer run more significant, in stopping Iran short of a nuclear bomb.