A Syrian refugee child sleeps on his father's arms while waiting at a resting point to board a bus, after arriving on a dinghy from the Turkish coast to the northeastern Greek island of Lesbos, Sunday, Oct. 4 , 2015. AP Photo/Muhammed Muheisen

How Fear Slammed America’s Door on Syrian Refugees

As millions flee from war to uncertainty or death, ‘national security concerns’ have kept US arrivals to a trickle.

The United States, which accepts more refugees per year than any other country, has all but closed its door to the millions of Syrians who are part of the world’s largest refugee crisis since World War II. A recent decision to admit more Syrian refugees this year opened that door a crack, but the Obama administration insists that national security concerns constrain it from going further. Yet officials at more than a dozen agencies could not point to any specific or credible case, data, or intelligence assessment indicating that Syrian refugees pose a threat.

The officials generally funnelled questions to the Department of Homeland Security.

“Certain groups have openly stated they will attempt to exploit the current situation with respect to large numbers of migrants seeking asylum in Europe and refugee resettlement,” said a DHS official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because department leaders would not authorize anyone to speak on the record about the threat assessment of Syrian refugees. “We must balance a very real threat with the potential propaganda value here.”

But the official was unable to provide evidence that Syrians refugees might pose a threat. “There is no particular trend that we have seen in the refugee population, nor has recent history shown – and open source reporting speaks to this — that with refugees who have entered [the U.S.] there has been a prevalence — a proclivity toward terror-related activities,” the DHS official said.

U.S. policy toward refugees from the war-torn Middle East remains bound by the infinitesimal chance that a foreign terrorist might exploit humanitarianism to kill an American on U.S. soil.

‘Homeland Security Comes First’

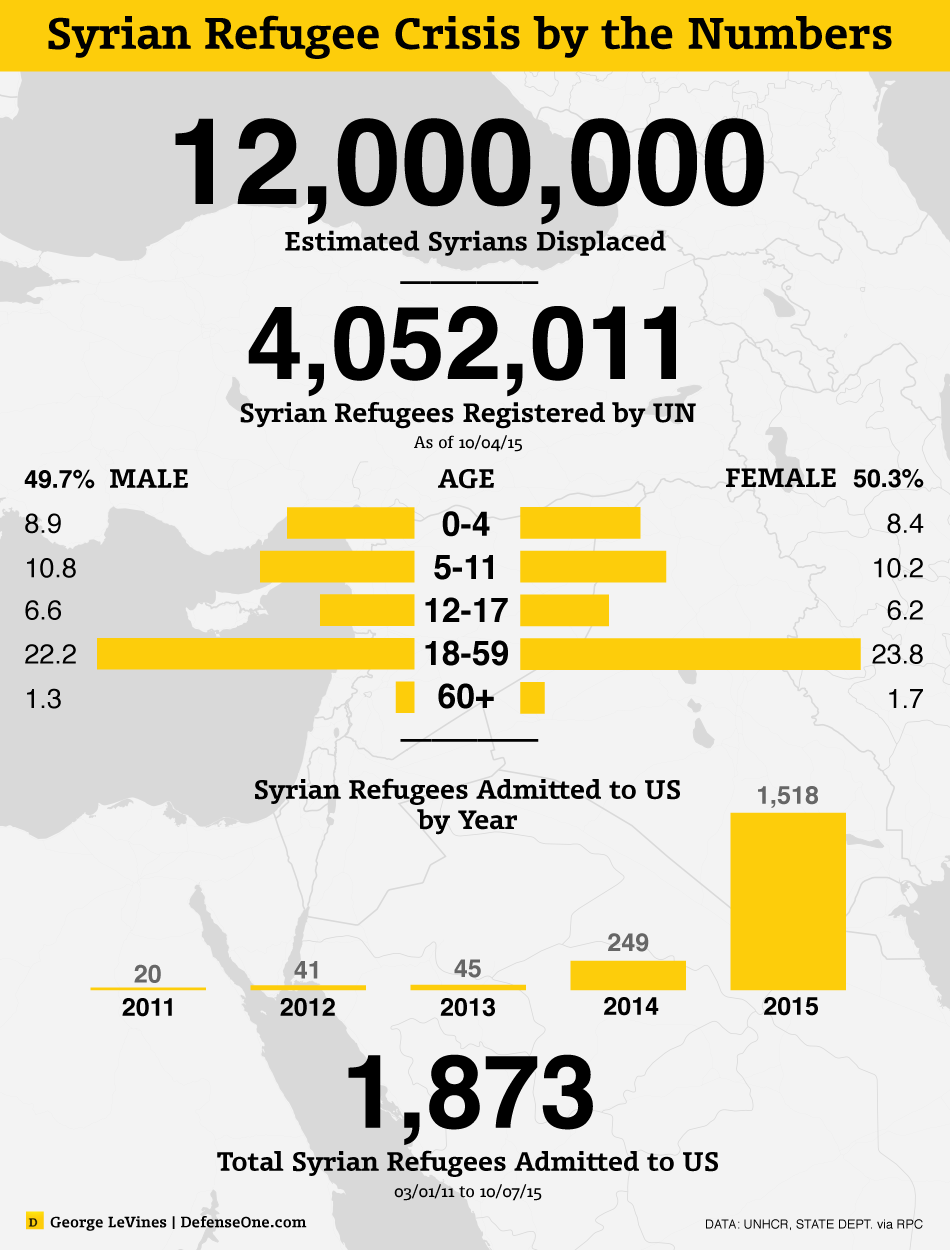

Since 2011, the U.S. has resettled just under 1,900 Syrian refugees. But the war in Syria, nearly five years old, has displaced more than 12 million people. Over four million Syrians — roughly one in five — have left the country, flooding the region and overflowing into Europe. Turkey has registered some 2 million Syrian refugees; Germany has said it will accept 800,000 this year.

Currently, the U.S. caps its global refugee intake at 70,000 per year. But spurred by the growing crisis — and horrific photos of its human toll — President Barack Obama recently raised next year’s cap to 85,000, and 100,000 by 2017. He has also pledged to take in at least 10,000 Syrian refugees in fiscal 2016, which began last Thursday.

But that’s easier said than done. Currently, it takes at least 18 to 24 months to resettle a Syrian refugee in the United States thanks to the lengthy clearance process imposed in the name of national security.

For a Syrian refugee fleeing the war and seeking a new life elsewhere, what comes first is registration with the United Nations’ refugee agency, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. All of the more-than-20,000 applications by Syrians for refuge in the United States received since 2011 have come from UNHCR, according to the State Department. UNHCR conducts rounds of interviews, first establishing identity and taking biometric data and later digging deeper into previous lives. UN workers determine whether a refugee falls into any of about 45 “categories of concern,” from serving in particular government ministries or military units to being in specific locations at specific times, even missing family members.

Given the UN agency’s limited resources and the urgency of so many cases, almost any flag will scuttle the refugee’s case indefinitely, said Larry Yungk, a senior resettlement officer who has worked on refugee resettlement for 35 years. Yungk helped start the Iraqi program in 2007 and now focuses on Syrians.

“These are things that would require more work, and since we have so many needs they tend to get deprioritized,” Yungk said, even though some concerns have nothing to do with security. “The stage we’re at is basically applying a very fine filter — even if there’s a question, we’re not going to proceed with resettlement.”

On average, UNHCR is screening out at least half of the cases, according to Yungk.

Still, he said, technology is rapidly improving security capabilities so they can focus on humanitarian priorities: UNHCR has already registered roughly 1.5 million refugees through iris scans.

“There’s really not a way to game that system,” he said. “My assessment is it would be very difficult to get through the system checks we have in place.”

After the UN referral comes the U.S.’s own security screening process, in which DHS and the State Department conduct their own, in-person interviews and use law enforcement and terrorism databases shared by the two departments, the National Counterterrorism Center, the FBI's Terrorist Screening Center, and the Department of Defense. DHS’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service told Defense One Wednesday that as of about a year ago, they began building up an added layer of enhanced review specific to Syrians, “to ensure potential gaps are covered.”

That process has resulted in resettling just under 1,900 of the 20,000-plus referrals since 2011.

The Obama administration says it's being prudent.

“The security of the United States homeland comes first,” White House spokesman Josh Earnest said. “And that’s what’s going to guide our decision-making process, and that’s why -- that, frankly, is why it’s not possible for the United States to, overnight, ramp up the number of refugees that are admitted to this country.”

‘Sending Fighters Into The Masses’

The administration’s argument it cannot do more because it’s hamstrung by national security obligations plays directly into politics. By law, the president sets the number of refugees, but Congress appropriates the funds necessary to cover them. Republicans already have introduced legislation to block Obama’s decision to let in more refugees, saying it could result in a “federally funded jihadi pipeline.”

“Members of ISIS have said that they are sending fighters into the masses seeking refuge,” said an aide for House Judiciary Chairman Bob Goodlatte, R-Va. Goodlatte was set to host a hearing on the crisis’ security impact on Wednesday, but it has been postponed.

Republicans cite February testimony from a House Homeland Security Committee hearing in which National Counterterrorism Center Director Nicholas Rasmussen said Syrians trying to come to the U.S. are “clearly a population of concern.” At the same hearing, Michael Steinbach, the assistant director of the FBI’s Counterterrorism Division, said of the security clearance process, "You have to have information to vet.” NCTC and FBI officials declined to clarify the comments.

It’s not easy to pin down the basis for the national security concern cited by U.S. lawmakers and administration officials. For nearly a month, Defense One pinballed between some 25 sources at the Capitol, the White House, the NSC, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the National Counterterrorism Center, the FBI, DHS, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service, the State Department, the Defense Department, the Defense Intelligence Agency and the CIA.

ODNI directed Defense One to four separate DHS agencies. NCTC ultimately directed queries to the FBI and DHS. The FBI also deferred to DHS headquarters. The CIA said the FBI would monitor refugees already in the U.S., but that DHS had the lead for questions on the Syrian refugee crisis. The State Department, Defense Department, and DIA referred Defense One to DHS and UNHCR.

Initially, however, Joseph Holstead of DHS’s citizenship and immigration service said the question was more appropriately directed to the State Department or the NSC – both of which sent Defense One back to DHS. Later, Holstead said the department couldn’t release the information without a Freedom of Information Act request. Defense One filed its FOIA on Sept. 21.

NSC officials did not respond to multiple requests for comment regarding the basis for their national security concerns, nor whether it requires a FOIA request.

In lieu of data, the DHS official ultimately gave this assessment: “We are not aware of any trends in general or with respect to Syrians.”

But several officials said the question may be difficult to answer because there is no quantifiable basis for the security worry that’s invoked to defend U.S. reluctance to let in more Syrian refugees. No U.S. official could, or would, point to any cases of Syrian refugees posing a threat.

‘Last Resort’

Wanting to do more for the refugees would seem to cut across the aisle. So too does maintaining strict requirements in the name of national security, despite the lack of data.

"Whenever there is an influx of refugees from any country, and especially a war zone like Syria with a glut of terrorists, there are going to be serious security concerns,” House Intelligence Committee Ranking Member Adam Schiff, D-Calif. told Defense One. “These security issues do not condemn us to inaction in the face of an unprecedented humanitarian crisis, however.”

Senate Intelligence Committee Chairman Richard Burr, R-N.C., asked rhetorically, “Do we have a reason to look at Syrians and say they’ve been involved in terrorism? Yeah!”

“But probably the larger thing is the intent expressed by ISIL and others to say we need to get people in this chain.” There is no evidence of that happening yet, however, he acknowledged. “I am assured, and by everything I’ve checked, that we are as thorough today as we probably need to be and probably can be.” On Tuesday, he told Defense One the national security concerns are “probably based more on what we don’t know than what we do know.”

Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., recently visited refugee camps in the Middle East. “Listen, national security comes first and so I don’t want to shortcircuit the vetting process,” he said, “But there are plenty of people in the those camps who pose no security risk to the U.S. — we always give priority to children, to people who are infirm and fragile situations.”

The politicization of the crisis has carried over to the 2016 campaign trail. Former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley, and now former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, have called for the U.S. to let in as many as 65,000 Syrian refugees.

Donald Trump said on Fox News Saturday that welcoming Syrian refugees could result in “one of the great military coups of all time if they send them to our country.”

Senate Foreign Relations Committee ranking member Sen. Ben Cardin, D-Md., told Defense One he didn’t know the basis for the cited national security concerns, “because I don’t think there is one.”

As she headed to a recent meeting with European ambassadors to discuss the refugee crisis, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., said simply, “I think they’re based on September 11.”

Many Syrian refugees resisted resettlement until lately, holding out hope they’d be able to return home, UNHCR’s Yungk said. “People think of resettlement as this golden door for everybody,” he said, “but for many people it’s a last resort.”

As for the Islamic State’s latest response to the exodus, instead of encouraging Syrians to infiltrate the refugee migration to the West, the terrorist group is threatening and cajoling people fleeing the region to stay and join the caliphate.