In this July 1, 1968 file photo, U.S. Ambassador Llewellyn Thompson, left, signs the Non-Proliferation Treaty alongside Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko. AP Photo

What a Major Arms Control Treaty Teaches Us About the Iran Deal

Nearly 50 years of the Non-Proliferation Treaty have proven one thing — multilateral agreements can work to make the world safer.

This week, with little fanfare, one of the world’s key restraints on the spread of nuclear weapons came under scrutiny, as a month-long review of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) concluded at the United Nations. Negotiated over the 1960s, the NPT was signed in 1968 and became international law in 1970. As specified by the treaty, members hold a conference every five years to assess the agreement. The exercise offers insight into our nuclear age, and perspective ahead of the coming debate about a deal to constrain Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

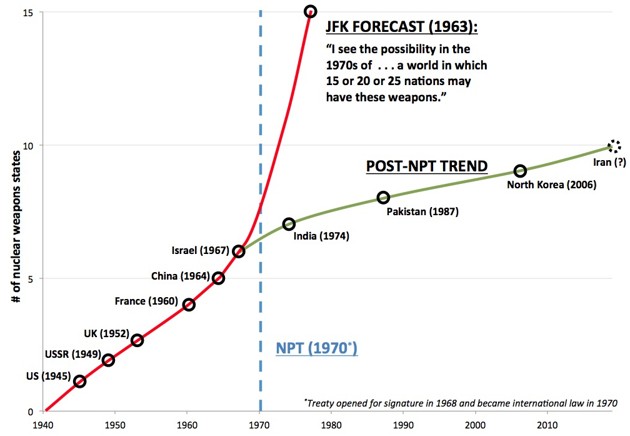

In the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, President John F. Kennedy determined that the nuclear order of the time posed unacceptable risks to mankind. “I see the possibility in the 1970s of the president of the United States having to face a world in which 15 or 20 or 25 nations may have these weapons,” he warned the world. “I regard that as the greatest possible danger.”

Kennedy’s estimate reflected the conventional wisdom during that period. As nations acquired the advanced technological capability to build nuclear weapons, most analysts expected them to follow in the footsteps of the first five nuclear powers and build their own arsenals. Kennedy’s purpose in stating his fears so starkly was to call for imaginative, unprecedented initiatives to avoid that future.

In response to this call, the United States and Soviet Union established a hotline to allow direct communication during crises; signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which outlawed nuclear tests in the atmosphere; and began negotiations to limit the spread of nuclear weapons. That effort eventually produced the NPT. States that joined the treaty foreswore nuclear weapons in exchange for other states, including their adversaries or potential enemies, making an equivalent pledge. In addition, the five nuclear-weapons states of that time promised to provide other members with technological assistance including nuclear-generated electricity and additional benefits of peaceful nuclear energy, as well as to work to reduce and ultimately eliminate their own nuclear arsenals.

Ever since the NPT became international law, skeptics in the United States have opposed successive arms-control agreements with arguments that have become virtually canonical. This canon begins by rejecting the concept of striking deals with sworn enemies. If the real objective is to change an adversary’s regime, or even destroy it, these skeptics say, how can the U.S. accept their commitments in agreements?

Ronald Reagan, for instance, was challenged by fellow conservatives when he began negotiating deals like the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty with the nation he named the “evil empire.” As George Will wrote in 1987, “Reagan has accelerated the moral disarmament of the West—actual disarmament will follow.” William F. Buckley’s National Review editorial asked: “Why is [the INF Treaty] bad enough to be called a ‘suicide pact’?” Because “the Soviets do not intend it to contribute to a general lessening of their worldwide operations.” Reagan insisted that he was capable of brokering agreements to reduce the risks of accidents or unauthorized actions that risked nuclear war with one hand, while redoubling his efforts to undermine the Soviet regime with the other. And he did just that. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

One argument advanced by critics of the NPT noted that many nations who signed up for the treaty were known cheaters; expecting them to comply with their commitments was naive, and verifying whether they were actually doing so would be impossible. Moreover, it was delusional to presume that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the official watchdog for the NPT, would be able to identify violations in states that could hide nefarious activity in hundreds of thousands of miles of territory. The IAEA has undoubtedly found that assignment challenging, and it has failed in this regard on several occasions. On balance, however, its record compares favorably with that of national intelligence agencies whose budgets are hundreds of times larger.

Critics also argued in the case of the NPT, as well as subsequent arms-control treaties with the Soviet Union, that success in signing agreements would lead the U.S. government to imagine that the problem of nuclear proliferation had been solved and shift its attention elsewhere—that it would, in effect, make leaders less vigilant about such a high-priority threat. But four and a half decades on, the U.S. intelligence community is hugely more capable and more focused on the spread of nuclear weapons than it was when the NPT was born.

The results, reflected in the chart above, are hard to deny. As of today, 185 states have signed up to the NPT and voluntarily renounced nuclear weapons. That is, virtually every state other than the declared nuclear-weapons states and a few outliers: India, Israel, Pakistan, South Sudan, and depending on who you ask, North Korea (Iran is a signatory). Members of the treaty include many countries that set out on the road to nuclear weapons and had the technical capability to complete the journey, but reversed course: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Egypt, Iraq, Italy, Libya, Romania, South Korea, Sweden, Taiwan, and the former Yugoslavia. In contrast to the 15 or 25 nuclear-weapons states JFK envisaged, today just nine have nukes: Britain, China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, and the United States. One state, South Africa, built nuclear weapons in the 1980s but then eliminated them during the transition from apartheid.

The NPT, of course, has been only one pillar of the global nuclear order. Others include the American “nuclear umbrella” (pledges to defend allied, non-nuclear states), U.S. security guarantees to Germany, Japan, and NATO members, credible military threats like those posed to Iran if it should seek to build a bomb, and even wars. Ironically, the U.S.-led military response to Saddam Hussein’s attempt to annex Kuwait in 1991 uncovered his secret nuclear-weapons program and destroyed it.

Still, given JFK’s nightmare that could have been, it’s worth recognizing the forces that bent this arc of history. The negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program represent a distinct case that must be examined on its own terms with careful attention to its specific facts. But the NPT’s record provides a backdrop against which to assess the latest round of canonical objections.