A global business empire raises the question: will the next president’s foreign policy serve America’s interests or his own? Jeff Martin

Tracking Trump’s National-Security Conflicts of Interest

A global business empire raises the question: is the president’s foreign policy serving America’s interests or his own?

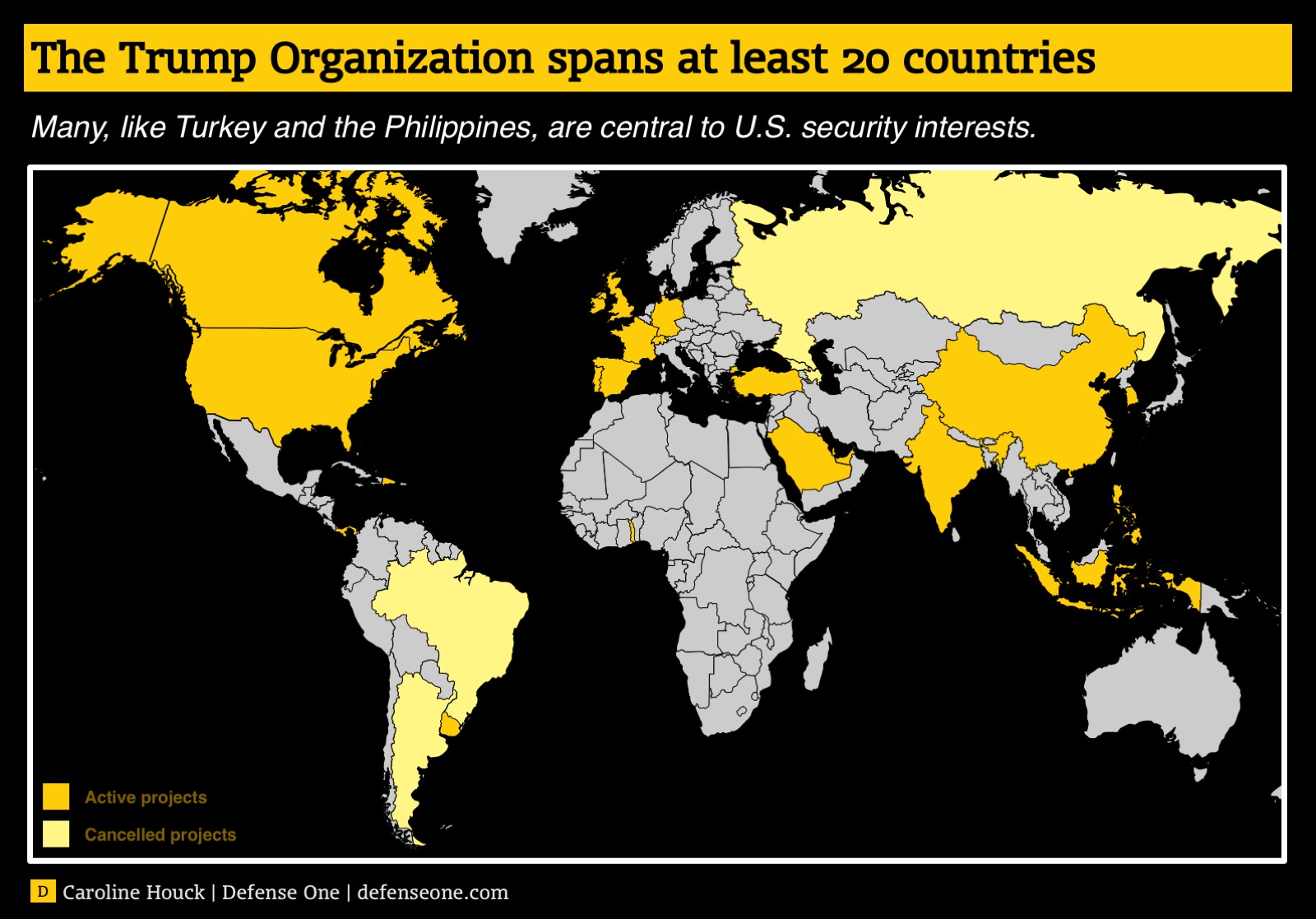

Last updated: April 24, 2020 — From close neighbors in Latin America to European allies in the fight against the Islamic State, Donald Trump has international entanglements like no previous commander in chief. Each of the president's business endeavors, critics say, offers an opportunity for foreign leaders and other actors to unduly influence U.S. policy through emoluments — or potentially, even extortion.

Keeping track of Trump’s national-security conflicts of interest is no simple matter. Though some potentially profit-inflected decisions have already attracted critical scrutiny, others have surfaced only in the international press, and still others may remain hidden by the Trump Organization’s opaque operating style. Other potential conflicts have emerged from the circle of advisors and extended family orbiting the White House, including Trump’s eldest son, his daughter, and his son-in-law Jared Kushner.

And even though Trump has given his sons control of at least some businesses, the potential conflicts will remain unless and until he creates a blind trust for his assets, legal ethics and national security experts say. The current arrangement falls far short of the mark; the president continues to receive reports on his company’s profitability, and can withdraw money or assets or revoke the trustees’ authority at any time. Shortly after taking office, Trump vowed to donate to the U.S. Treasury the portion of his business revenue that comes from foreign governments, a promise his lawyers quickly walked back. Still, in February, the Trump Organization cut the the U.S. government a $151,470 check, providing no details about who paid how much and for what.

Foreign governments have taken notice. A number of them have found ways to do favors for Trump’s projects in their countries. At least 11 foreign governments paid Trump-owned entities during his first year in office.

What follows is an accounting of Trump’s overseas financial interests, gleaned from open-source reporting, including the financial disclosure forms he filed as a presidential candidate in May 2016 and as president in June 2017. Released by the Office of Government Ethics and Federal Election Commission, these forms are light on details but provide broad estimates of Trump’s assets, income, and debt for the year ending May 2017, and the year before. Trump filed his 2018 disclosure on May 15; it could take several weeks for details to be made public.

We will update this article as information comes to light about Trump’s interests, including projects that are being cancelled or moving ahead.

More on our methodology here.

Click to see Trump’s business interests in:

See also:

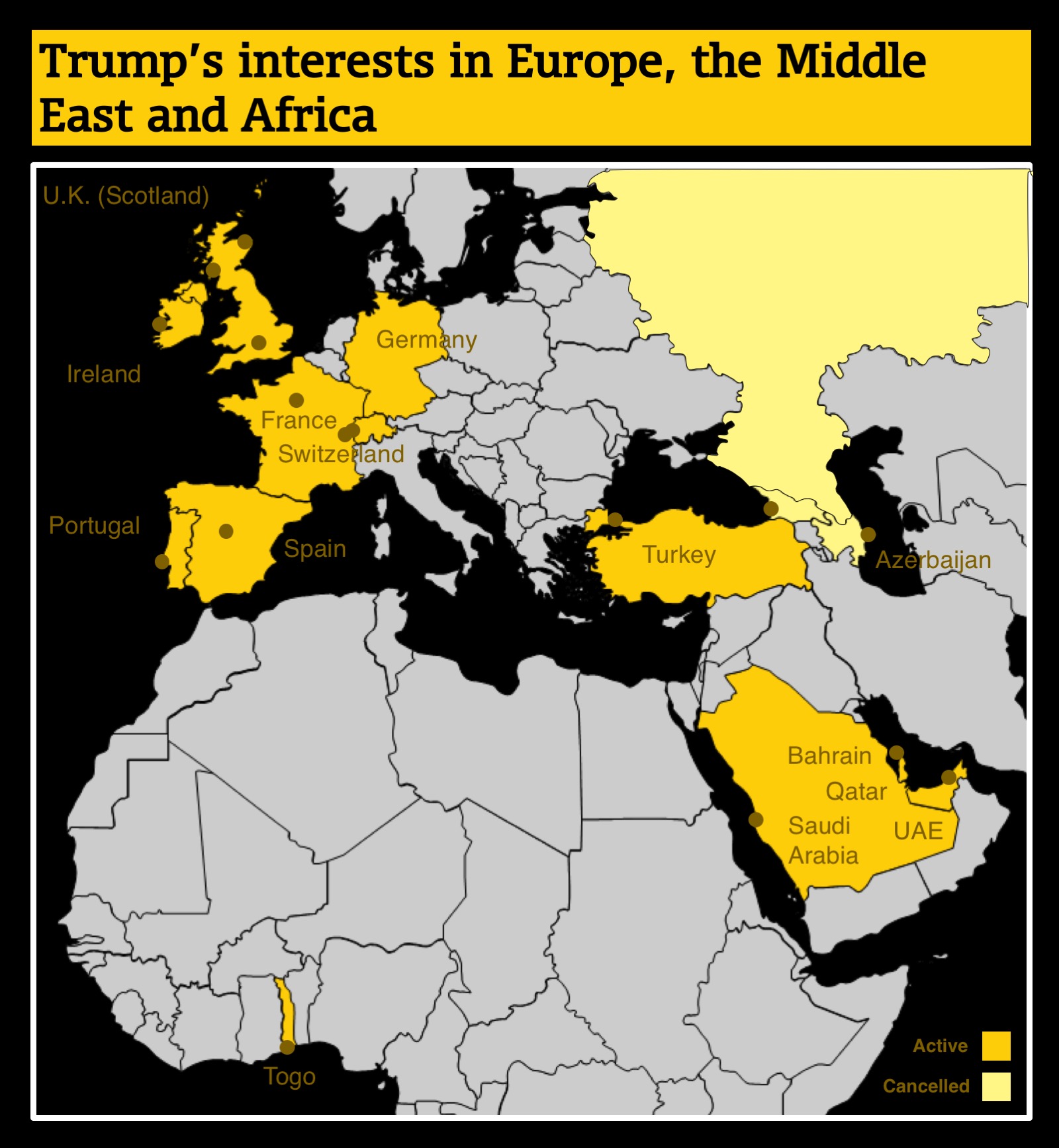

Europe, the Middle East, Africa

The U.S. has long maintained an intricate web of bilateral and regional Middle East security partnerships in the interest of regional stability. Its most visible military engagement, the coalition fight against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, is a complicated, multilateral effort that could grow even more complex with Trump’s financial interests.

Most notably, America’s NATO ally Turkey plays host to a pair of Trump Towers and contributes troops to the coalition fight in Syria. Turkey lets the U.S. and others fly combat strike and surveillance missions against ISIS from its Incirlik Air Base. But Turkey also has long-simmering issues with some separatist Kurdish groups the U.S. has welcomed into the fight, where they furnish some of the coalition’s most effective ground forces.

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has cracked down on Kurdish and opposition groups, angering European and American officials and publics. But Pentagon officials privately say that Erdoğan’s military commanders, at least, remain committed to the fight against ISIS, and in any case, Turkey’s cooperation is needed.

Trump’s rise has also rocked relations with European leaders, who are questioning America’s commitment to defend its NATO allies, and nervous over Trump’s public yearning for Russian President Vladimir Putin’s friendship.

Here are Trump’s business interests in the Middle East and Europe:

Turkey

- The Trump Towers Istanbul project is reportedly being used as a bargaining chip to sway the president-elect’s policy interactions with Turkey. It is not the first time his business and policy have collided there: When Trump proposed banning Muslims from entering the U.S. in 2016, Erdogan called for Trump’s name to be removed from the towers, threatening the licensing fees that netted Trump $1 million to $5 million on each of his past two filings. Trump has recognized the conflict of interest.

Saudi Arabia

- Trump’s interest in Saudi Arabia is still largely that – an interest. Ivanka Trump identified it as one of three Middle Eastern countries in which the Trump Organization planned to open hotels. Trump touted his transactions with Saudis on the campaign trail and registered eight companies tied to the country after he started his presidential campaign, all seemingly linked to a potential hotel in Jeddah. But there has yet to be any other progress, and he has reportedly dissolved half of those corporations. That’s backed up by his most recent disclosure: Trump dropped ownership in four of those companies in 2015, and dissolved the other four the week after the 2016 election.

- Saudi Arabia pledged $100 million to Ivanka’s proposed World Bank Women Entrepreneurs Fund on the same May 2017 weekend that a visiting Trump announced a record-breaking $100-billion arms deal with the Gulf kingdom.

UAE

- Trump International Golf Club Dubai is an 18-hole golf course that opened in mid-February 2017—with Eric and Donald Jr. in attendance—after its scheduled 2016 opening was pushed back. Trump’s proposed Muslim ban appears to have been forgiven, and his partner has announced a new series of villas overlooking the course that will also be Trump-branded. In fact, the Trump brand is now helping sell properties, his business partner said. In the first few months it was open before Trump filed his 2017 disclosure, the golf course earned him just under $13,000 in management fees.

- Trump World Golf Club, a second golf course (designed by Tiger Woods) and club built in another luxury development with the same partner. Expect it to open in 2018.

- Two accompanying streams of royalties, each worth $1 million to $5 million in the year ending May 2016, and 12 associated organizations identified in the filing. In May 2017, Trump’s two sons met with the organization’s Dubai partner on both resorts, Hussain Sajwani, to discuss “new ideas.” Trump reconnected with Sajwani at the World Economic Forum in Davos this January.

Qatar

- Trump’s interest in Qatar was largely speculative as well. Though it was one of the three Middle Eastern countries in which the Trump Organization said it planned to open hotels, and the 2016 disclosure revealed four associated companies, there hasn’t been any apparent progress. Trump dissolved all four companies the week after he was inaugurated, according to his most recent disclosure. Over the long term, the door may not be totally closed; the Trump Organization renewed web domains for several potential Qatari projects.

- State-owned Qatar Airways has been a tenant in Trump Tower Manhattan for years.

Ireland

- The Trump International Golf Links and Hotel Doonberg combo, which opened in 2002 and has four associated entities registered in the Irish town. Trump earned more than $10 million in golf-related revenue from Doonberg in the year ending May 2016, though he more recently made headlines there over an embattled plan to build a seawall to protect the resort from rising sea levels. Trump reported another $12 million from the course on his 2017 form. But for all that revenue, the course lost $2.3 million in 2016; 2017 profits won’t be available until late 2018.

Scotland

- Trump International Golf Links Scotland and the MacLeod House and Lodge in Aberdeen is the golf course whose view and value Trump said would be harmed by offshore wind farms – a fight settled by the United Kingdom’s courts that he rekindled in a meeting with British politician Nigel Farage in 2016. Plans to expand the resort are proceeding, the Guardian reported in January 2017, despite strong local opposition. The local council is considering an application from the resort to add a second 18-hole golf course and more housing. Trump reported $3.8 million in golf-related revenue from the resort on his most recent disclosure, but the course is operating at a loss.

- Another golf-and-resort combo, Trump Turnberry, on Scotland’s west coast. The original hotel and prestigious golf course date to the early 1900s; Trump bought the property in 2014 and spent two years renovating it. Was it worth it? That’s still to be determined: Although the May 2016 financial disclosure reports more than $18 million in golf-related revenue from Turnberry and another $14 million on the more recent form, local business filings showed an overall operating loss of about $24 million for Trump’s two Scottish golf courses in 2016. And Reuters questions whether his golf investments are underwater.

- DT Connect Europe, located in Scotland and owned by another of Trump’s 11 Scottish businesses, owns a Sikorsky S-76B helicopter, which he valued between $1 million and $5 million in the disclosure. The company also earned between $100,000 and $1 million in rent for unknown holding(s), according to Trump’s latest disclosure.

Georgia

- After the election, a plan for a Trump Tower in the resort-and-casino town of Batumi was suddenly revived. Announced in 2012, it had fallen dormant when the country’s political situation changed. But at the start of December 2016, the project’s planned builder said it could move forward as soon as January 2017. Then early that month, Trump and the builder, the Silk Road Group, announced they decided “to formally end the development of Trump Tower, Batumi.” The Silk Road Group said it will build a luxury tower in the town independently. Trump’s two companies related to the project are now dormant, according to his 2017 disclosure.

Azerbaijan

- To establish a now-abandoned Trump Tower in Baku, Trump partnered with an Azerbaijani businessman and then-government official that may be tied to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. Originally announced in 2014, the planned development stalled and was removed from Trump’s hotel portfolio website after the Azerbaijani economy crashed. Trump nevertheless earned more than $320,000 in management fees for the property in the year leading up to May 2016 financial disclosure filing. Midway through December 2016, the Azerbaijani Embassy hosted an event at Trump’s hotel in Washington, D.C. The day after, Trump lawyer Alan Garten said the organization was canceling its licensing deal with the Baku property. Trump reported no income from the dissolved Baku project in his 2017 disclosure.

Russia

- From autumn 2015 to early 2016, as Trump was running for president, the Trump Organization pursued a deal to develop a Trump Tower in Moscow. The company signed a letter of intent for the branding project, which subsequently stalled, leading Michael Cohen, a top Trump executive, to seek help from the Kremlin. (Cohen did not recall receiving any response to his entreaty, according to documents submitted to Congress in August 2017.) Cohen told Congress the company abandoned the project in January 2016, but he continued to pursue the deal at least until May of that year, according to text messages between Cohen and Felix Slater reported by Yahoo News in May 2018.

- Trump has repeatedly said he has no investments in Russia. (He has made attempts over the years to enter the country’s real estate market, and in 2013 hosted his Miss Universe pageant there.) Justice Department Special Counsel Robert Mueller subpoenaed the Trump Organization for records, including some related to Russia, in March.

Others:

- Germany’s Deutsche Bank holds $300 million of Trump’s debt, with a clause that if he were to default, the bank could go after his other assets. The bank’s efforts to restructure the debt with a different guarantee (to avoid awkward scenarios of collecting from a sitting president of the U.S.) have stalled. U.S. Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s team subpoenaed the bank at the end of 2017 for information on the Trumps’ accounts there, as part of the team’s investigations into Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. election.

- TAG Aviation, an aircraft chartering, management, and maintenance company owned by the Trump conglomeration, operates out of airports in Bahrain, France, Switzerland, the U.K., Spain, Portugal, and Togo. It netted the Trump Organization over $7 million over the past year — for leasing Trump’s Boeing 757 to his campaign.

Asia

In the face of a rising China, the U.S. is involved in what Defense Secretary Ash Carter called “a long campaign of firmness” to keep the Asia-Pacific region secure and stable.

The U.S. has multiple allies in the region — via bilateral treaties with Japan, South Korea and the Philippines, plus a multilateral pact with those countries and several others — and stations military personnel in several places. But sustaining the Asia-Pacific’s 60 years of relative stability and American leadership there requires effort as China’s global ambitions grow.

The latest flashpoint is the South China Sea, where the U.S.’s efforts to push back against aggressive Chinese encroachment are complicated by, among other things, Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte, who has been increasingly hostile toward the U.S. and deferential toward China.

The Trump Organization has interests in the Philippines and several other countries:

Philippines

- Trump Tower Manila is an unabashedly luxurious project that was quietly opened in 2017. Trump’s partner on the project, Jose E. B. Antonio, was named as a special envoy to the U.S. before the election. Trump received up to $5 million in royalties from the project in each of the last two years reported on his disclosures, funneled through one of his two Trump Marks Philippines corporations.

China

- Trump owes the Bank of China $211 million, debt he accumulated in a 2012 refinancing of his stake in 1290 Avenue of the Americas, a 43-story skyscraper in Manhattan. The debt is due in 2022.

- Much of Trump’s interests in China are speculative. Trump Organization officials have previously said they have a team in Shanghai and are looking to establish hotels and in Shenzhen and Beijing. Trump’s disclosure notes nine companies associated with the country, but so far he hasn’t cracked the Chinese market. Post-election, any plans to expand the hotel chain into China are “pretty much off,” Trump Hotels CEO Eric Danziger said at an investment summit in January 2017.

- But other business prospects might still be viable: After a protracted legal battle, China granted Trump a 10-year trademark for Trump-branded construction service just a few weeks after his inauguration. Trump received preliminary approval for at least 38 other (more recently filed) trademarks in the country several weeks later. And Ivanka Trump, the president’s daughter-cum-advisor, had three of her brand’s trademarks approved by the Chinese government on the same day in April 2017 she dined with the country’s president.

- China’s largest state-owned bank pays the Trump Organization about $2 million a year to rent office space in Manhattan’s Trump Tower. The bank, which was the building’s largest tenant as of a few years ago, can renegotiate its lease in 2019—before Trump’s four-year term is over.

- State-owned Chinese companies have entered new deals with Trump-branded properties elsewhere in the world since his inauguration. And Chinese companies are expected to put up $500 million in loans to a development project in Indonesia that will include Trump Organization hotels, golf courses and condos. That investment was announced in May 2018, just days after Trump promised to help save Chinese electronics manufacturer ZTE, pushed to the brink of bankruptcy by U.S. sanctions for selling cellphones in Iran.

- TAG Aviation, Trump’s aircraft-services company has a Hong Kong-based subsidiary that serves the Asian market.

India

- Trump Towers Pune is a pair of towers several hours from Mumbai. A pair of state and local investigations into the building have yet to slow down rentals nor lower the price of apartments that sell for 35 percent above their nearby peers. The Trump Organization ended “exploratory talks” for a second development in Pune, Trump lawyer Alan Garten said in early January 2017. Trump has not reported any income from the four companies he has associated with the Pune towers on either of his last two financial disclosure forms.

- Trump Tower Mumbai, Trump’s second attempt to get into the Mumbai market, generated $1 million to $5 million in license fees, according to the May 2016 disclosure. On the following year’s form, the royalties were only $100,000 to $1 million. On target to be completed by 2019, the building was about 60 percent sold by spring 2017, its developer said that April.

- In the New Delhi suburb of Gurgaon, Trump will license his name to a pair of residential buildings called Trump Towers Delhi NCR. The deal with local developers M3M and Tribeca Developers was reportedly agreed to before Trump’s election, but was only announced in October 2017. The project launched this January, and the developers are promising to fly the first group of condo buyers to the U.S. for an event with Trump’s son. (Or they could just meet him at a dinner for condo buyers when he visited the country in February 2018.)

- Also in Gurgaon, a fledgling deal with Indian developer Ireo to build a Trump tower had already netted between $100,000 and $1 million in royalties in the year ending May 2016, and again in the time period covered under the 2017 disclosure.

- And in Kolkata, another prospective Trump tower in partnership with Unimark Group has completed the design-review phase and launched in November 2017. Apartments in the 140-unit planned building are selling quickly. It, too, generated $100,000 to $1 million in royalties in the time period covered under the 2017 disclosure.

- 16 other related corporations and associations.

South Korea

- Trump World Seoul, the first development to which Trump licensed his brand.

- Two associated companies, including a joint-venture with the partner who built the condo properties.

Indonesia

- A planned Trump International Hotel and Tower Bali, announced last year and slated for completion in 2018 is a 100-hectare resort that would be Trump’s first hotel in Asia. The Bali government plans to build a toll road that would halve the time it takes to get from the airport to the resort.

- A second deal is with the same partner from the Bali project to build Trump International Hotel and Tower Lido in West Java, about 100 kilometers south of Jakarta. It would include the resort as well as residences and a golf course. It, too, is getting a new toll road built for it to reduce travel time. Though a Indonesian state-owned firm is building the route, Trump’s partner, MNC Land, plans to pay construction costs. And Chinese companies are expected to build the complex’s other main attraction, a large theme park that will be backed up by $500 million in loans — a sum that’s about half the capital the project needs, “putting its success or failure in the hands of decision-makers in Beijing,” Agence France Presse reported in May 2018.

- Each deal netted Trump between $1 and $5 million in royalties, plus $83,333 in management fees in the year ending May 2016. The following year, Trump reported $190,476 in management fees for each hotel, but no royalties. Between the two projects, Trump has 16 companies associated with Indonesia. Trump spokeswoman Amanda Miller told the New York Times at the end of 2016 that the two projects “will proceed as planned.”

The Americas

Though the region is not without its security issues, Latin America and the Caribbean have historically sat squarely within the U.S.’s sphere of influence. The U.S. maintains a multilateral military treaty with large swaths of Latin America and the Caribbean, and Canada is a member of NATO.

But in recent years, China and Russia have started testing the waters, and may see Trump’s election as an opportunity to move in further.

Trump’s financial interests that could complicate or undermine his dealings with the region include:

Canada:

- The Trump International Hotel and Tower Vancouver opened with a soft launch in the days around the presidential inauguration and had its grand opening at the end of February 2016. One of the first patrons of its event space? The American Chamber of Commerce in Canada, which moved a late-January event to the hotel after running into logistics problems with its previous venue. Trump has four organizations associated with the tower. According to Trump’s 2017 report, the Trump Organization earned over $5 million in royalties and $21,576 in management fees from the new hotel.

- A Russian state-run bank helped finance a deal to prop up the failing Trump International Hotel and Tower Toronto and eight associated corporations, partnerships and bank accounts. The Trump Organization does not own the property, but managed the hotel and licensed the Trump name to the now-defunct developer. The bulk of the property went on the auction block in early January 2017 and was bought by its creditor for $223 million two months later. That didn’t stop Trump from earning over $500,000 in management fees from the hotel over his 2017 reporting period, but it may be the last of the money coming in from Toronto. In the summer of 2017, the owners reached a deal to remove Trump’s name from the building.

- Trump Education ULC and an account with the Royal Bank of Canada.

Panama

- Trump Ocean Club International Hotel and Tower Panama and eight associated corporations. In the period covered under Trump’s 2017 disclosure, the property brought in between $100,000 and $1 million in royalties, plus over another $800,000 in management fees. The royalties were a bit more lucrative the year before, generating between $1 million and $5 million, according to the May 2016 form. But the hotel owners themselves are less thrilled about the connection — in November 2017, they started an effort to strip the Trump name from the hotel and sever management ties. The acrimonious legal battle devolved to physical blows in late February before the Trump Organization was evicted in March. The law firm representing the Trump Organization sent Panama’s president a letter asking him to intervene in the dispute in March — a move congressional Democrats are questioning.

- Former Panamanian President Ricardo Martinelli, who helped Trump launch the property and sat the board of a bank that managed funds for the Ocean Club, now faces extradition from the U.S. after fleeing multiple corruption charges.

- The Panamanian government has done favors for the Trump project, according to research done by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. It has finished off sewer and water pipes after the original contractor defaulted and has used the resort for government events.

Brazil

- The Trump Rio de Janeiro Hotel, which opened uncompleted to host guests for the Summer Olympics in 2016. After investments the hotel were named in a sweeping criminal investigation of the country’s pension fund managers, Trump Hotels said in December it was pulling out of the licensing deal.

- A planned $2.1-billion development of Trump Towers Rio, which was announced in 2012 but has yet to break ground. A recently filed criminal investigation into the corporate office project likely foreshadows yet more delays.

- Eight associated corporations and organizations linked to Rio or Brazil more broadly.

Argentina

- The long-stalled Trump Tower Buenos Aires, which showed signs of life after a post-election phone call between Trump and Argentine president Mauricio Macri. Though both parties refuted a report saying the two discussed the property, and the building’s permitting process isn’t finished, Trump’s partner on the project announced three days after the phone call that construction would start in 2017. In January 2017, an unnamed spokeswoman said Trump would not build the Buenos Aires tower.

Uruguay

- Trump Tower Punta del Este, which delivered between $100,000 and $1 million in royalties in the year ending May 2016, via one of the two associated corporations Trump maintains in the country. A promotional video released by the hotel showed the construction progress; real estate groups say expect the 26-floor tower to be completed at the end of the year, or perhaps May 2019.

United States

- Trump’s business empire is global in nature, but at home domestically. In the U.S., the Trump organization maintains multiple hotels, golf courses, and other properties — including Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s Florida resort — and has at least $250 million in unsold real estate whose sales could lead to conflicts of interest with individuals or foreign state-owned entities. It will be difficult to tell if such a conflict arises, because about 70 percent of Trump properties bought over the last year were purchased through limited liability corporations designed to obscure owners’ identities. (That’s always been a feature in luxury real estate deals, including Trump’s, but is part of a trend: The secretive, all-cash deals have comprised a larger share of his business since the late 2000s, a Buzzfeed News analysis found.)

- Many foreigners have bought or invested in Trump’s properties (see: this, this or this, for example). This is by no means unusual in the world of luxury real estate. So we’ll focus only on the ties between Trump’s U.S. businesses and foreign governments. For example, China’s largest state-owned bank and Qatar’s state-owned airline are both tenants in Trump Tower Manhattan, and the Qatari government bought its fourth condo from the Trump Organization in January 2018, right after a judge dismissed an emoluments lawsuit challenging purchases like that one.

- Trump’s new Washington, D.C., hotel is conveniently situated on Pennsylvania Ave. for visiting officials and dignitaries, halfway between Congress and the White House. Critics say it has also become a one-stop-shop for any of them looking to get in the president’s good graces. A few examples from the first year of Trump’s presidency: Bahrain and Kuwait hosted their national day celebrations there in December 2016 and February 2017, respectively. The Malaysian prime minister hobnobbed there while visiting Washington. And the former Mexican ambassador to the U.S. said in November that the State Department encourages diplomats to stay at the hotel. All that helped the hotel turn several million dollars in profit in its first year. Most luxury hotels operate at a loss in their first few years. The latest foreign government guests of Trump Hotel: the Philippines.

Caribbean Islands

- The Trump Organization is re-engaging in a deal, dormant since the 2008 financial crisis, to develop beachfront estates in the Dominican Republic. Less than a month after Trump promised “no new foreign deals,” Trump’s son Eric visited the land, which is valued between $1 million and $5 million in the disclosure. The Trump Organization's general counsel, Alan Garten, told the AP the deal was never dead—though nothing has been built in a decade and Trump’s organization had previously sued its local partners. In January 2018, his partners on the island were granted permits and financial incentives to build 17 towers, including the project linked to the Trump Organization.

- Le Chateau des Palmiers, a residential rental property on St. Martin, generated between $100,000 and $1 million in rent payments over each of the preceding years. It went on the market in April for a reported $28 million — about $10 million more than what Trump likely paid for the property in 2013. It has since dropped to $16.9 million, though that was before Hurricane Irma destroyed much of the island, including the area where Trump’s property is.

- Land and real estate investments on the tiny Grenadine island of Canouan, where Trump launched a development of a golf course and accompanying villas in 2004. Though the casino he also managed there has since gone bankrupt, the golf course has been rebranded and the villas didn’t work out, he still had four active corporations linked to the island at the time of the filing. One of them netted $3 million in land sales – possibly the last of his involvement with the island? Trump didn’t report any income or assets on the island on his more recent filing.

- DJ Aerospace Bermuda Ltd, a perhaps-inactive corporation that is wholly owned by the president-elect. At least until 2011, Trump had registered a Boeing 727 on the island. He has since sold that plane.

Pending U.S. Litigation

There are several lawsuits filed in U.S. courts against President Trump regarding conflicts of interest between his presidency and ongoing business ties.Others have been dismissed for lack of standing.

- Maryland and the District of Columbia sued the president in June. The suit, filed jointly by Maryland and D.C.’s attorneys general, alleges Trump has violated constitutional anti-corruption clauses by “receiving millions of dollars in payments, benefits, and other valuable consideration from foreign governments.” A pretrial hearing was held in January to decide whether to take up the case, and in March the judge refused to dismiss the suit.

- Almost 200 Democratic members of Congress also sued Trump in June with a complaint similar to D.C. and Maryland’s.

- In March, a D.C. restaurant sued Trump, saying his D.C. hotel constitutes unfair competition.

Other Resources

This article focuses on Trump’s international properties and domestic projects with any ties to foreign governments. For more information on other aspects of the president’s business empire, here are more resources, including:

- A domestic and international tracker of the Trump Organization

- A list of his foreign business partners

- An overview of his debts

- A summary of how domestic conflicts may arise

- The financial disclosure forms for officials in his administration

- An interactive map of his network

- A rundown of how he profited from the presidency in his first year in office

Methodology Notes:

Foreign business interests were identified using the June 2017 financial disclosure, May financial disclosure, public statements from Trump or his children, and other open-source data. The disclosure was not reviewed by regulators; more Trump-related companies and investments may exist.

Each interest is listed in the region where it does or expects to do its primary business, not where it may be registered or headquartered. As an example, DT Marks Worli LLC was incorporated in Delaware in 2013 and is located in New York, according to the filing, but is licensing the Trump name to a developer building a Trump Tower in the Worli neighborhood in Mumbai. As such, it’s included here as an interest in India.

Finally, the financial disclosure lists more than 500 corporations and associations in which Trump held positions, most often as a director or president of the group. A number of these hint at the Trump Organization’s ambitions to expand its international brand, but weren’t linked to any assets or income. If no ongoing operations or public statements from Trump or his organization could be found for these companies, they were not included here. An LLC and a corporation, both sporting the name Trump Marks South Africa, are two such examples.