sponsor content What's this?

Spotlight: Defense Industrial Ecosystems in the Asia-Pacific

Presented by

Forecast International

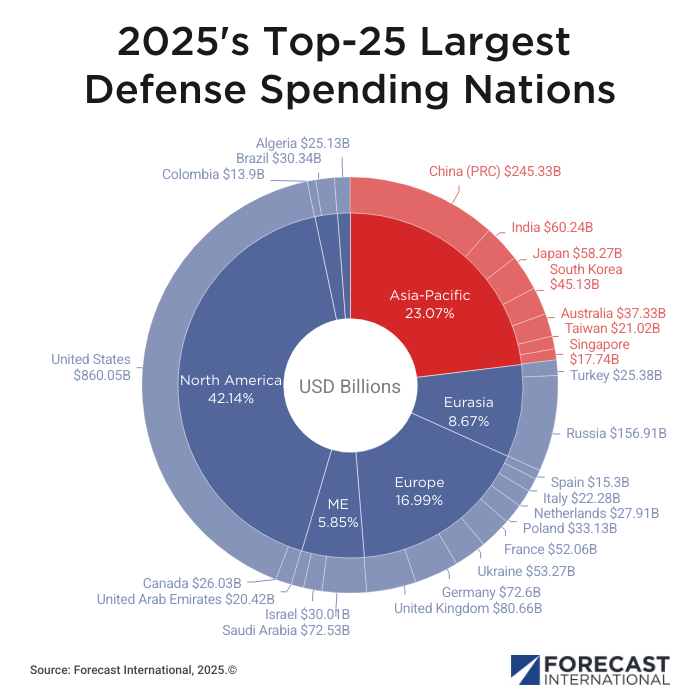

The Asia-Pacific region is home to one of the world’s most dynamic defense markets and a driving factor in the global arms trade. According to Forecast International figures, of the top twenty-five largest defense spending countries in the world, seven reside in the Asia-Pacific, including the second-largest global military spender in China.

Not only China but increasingly Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan are becoming more and more capable of self-sufficiency in areas of defense technologies. India, too, continues to push for greater shares of indigenous capability in its military inventory in order to diminish its longstanding dependence on foreign-sourced hardware.

South Korea

The growth of South Korea’s defense industrial sector follows a long journey dating back to the early 1970s when shifts in U.S. foreign policy prompted Seoul to recognize the vulnerability of being a sole-source militarily dependent nation. The buildup followed U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam and the subsequent election pledge made by President Jimmy Carter to pull U.S. forces out of Seoul. Faced with its heavily armed neighbor to the north, South Korea wanted a greater degree of self-sufficiency in arms.

After decades of investing in defense-related research and development initiatives and building a solid military manufacturing foundation South Korea today features a defense industrial base churning out equipment across the air, sea, land, and defense electronics spectrum. With the U.S. as a key strategic ally, South Korean equipment designers and producers place an emphasis on maintaining a level of compatibility with American systems, thereby ensuring simpler logistics chains and degrees of interoperability with U.S. and NATO counterparts.

With its success in producing tanks, self-propelled howitzers, multiple launch rocket systems, helicopters, submarines, naval surface combatants, jet trainers and now a 4.5-generation combat aircraft, South Korea has emerged as a viable alternative to more expensive U.S and European systems on the global arms market.

What South Korean arms might lack at the highest end of the technology spectrum are made up for in lower costs, faster deliveries and often more generous terms relating to technology transfer, industrial offsets (such as localized workshare) and financing offered to the buyer.

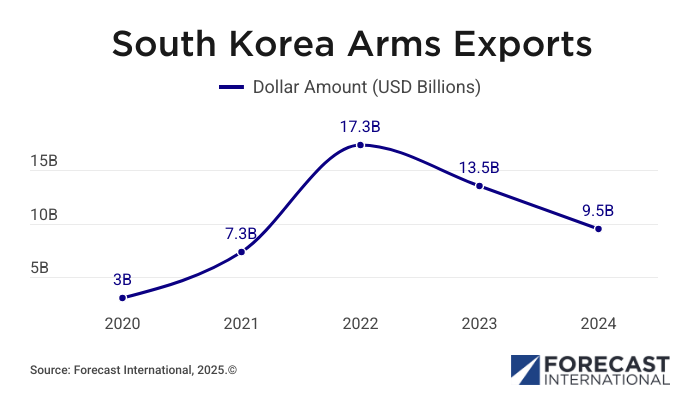

The upshot is that South Korean exports are now booming, in part due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but also due to order backlogs and production bottlenecks confronting U.S. and European competitors. As a result the country's arms exports have continued to push into new foreign markets and achieve sales increases from $7.3 billion in 2021 to approaching $20 billion in 2024.

The South Korean defense sector is dominated by a few large conglomerates - referred to as chaebols - such as Hanwha Group, Hyundai Heavy Industries and Hyundai Rotem, Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI), and LIG Nex1. However, the sector also features 30-40 midsize companies and another 60 smaller, more diversified firms serving niche roles.

Following the end of the Second World War and the subsequent U.S. military occupation, Japan was prohibited from re-engaging in military design and production. This restriction was eased with the start of the Korean War in 1950, as the U.S. sought to mobilize Japanese resources in its effort to halt communist advances on the Korean Peninsula. However, it was not until 1954 that Japan's local industry began producing material for its own military. Much of this was of American design, with only slight indigenous modification.

Gradually, local industry expanded into a broad variety of military equipment and, over the next few decades, provided an increasing share of the Japan Self-Defense Forces' hardware. This focus on domestic production to meet the equipment requirements of the Japan Self-Defense Forces enabled Japan to grow its defense-industrial base. However, despite the supply of basic equipment for its own military, years of declining defense expenditures following the end of the Cold War, coupled with government-imposed export restrictions, resulted in a lack of military technological breakthroughs and a sluggish domestic defense sector.

The self-imposed arms sale ban - known as the "Three Principles" doctrine - was formed in 1967, while the Cold War continued to cast its shadow over the international arms trading environment. The three principles blocked Japanese manufacturers from exporting their wares to communist bloc countries, countries subject to U.N. arms embargoes, and those nations involved in (or likely to become involved in) international conflicts.

This export policy was later expanded to the degree that much of the hardware produced in Japan was banned from being sold outside the country. While popular with the Japanese public due its pacifist-minded tendencies, the export policy came under increasing criticism in Japanese defense circles. The policy was criticized because it prevented Japan from becoming involved in jointly developed military equipment, and because it was seen as hindering the country's local defense-industrial base by limiting sales opportunities abroad that would allow for the economies of scale required of an advanced defense-industrial sector. As a result of the policy, Japan’s defense sector shrank as companies stopped military equipment production due to low profitability and high development costs.

Today Japan is no longer inhibited by arms sales restrictions and the government has been steadily increasing annual defense spending and emphasizing military production as part of a broader national economic security approach.

In June of 2023, the Japanese legislature passed the Act on Enhancing Defense Production and Technology Bases, which aims to bolster the domestic defense industrial sector by establishing mechanisms for the government to support local defense companies and supply chain diversification and reduce overreliance on foreign suppliers. Additionally, the goal is to support defense exports - a goal which took a major step forward on August 7, 2025, when Australia’s government announced a decision to adopt Japan’s updated Mogami frigate design to meet a Royal Australian Navy requirement for a new class of general-purpose warships.

Currently Japan’s defense sector relies primarily upon a few large manufacturing conglomerates, such as Subaru Corporation (formerly Fuji Heavy Industries), Kawasaki Heavy Industries, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. In order to maintain smaller subcontractors within the larger military industrial chain, Tokyo will need to signal that government financial support and greater sales opportunities abroad are reasons to remain in the defense business.

India

Following decades of sputtering attempts to create a largely self-reliant defense industry and wean the Indian Armed Forces off their dependency on foreign armaments, India is slowly beginning to show progress thanks in part to the government’s “Make in India” policy emphasizing indigenous production.

India's defense industry has traditionally been dominated by the state. Successive governments remained protective of the country’s defense sector, viewing it as a strategic anchor in the nation’s economic development, therefore state-owned defense primes were championed and local private defense companies formerly prevented from competing for domestic contracts. All the while, India remained largely dependent on foreign material to equip its military, with Russian-sourced hardware the primary choice, prior to increased diversification in the past two decades.

But with the implementation of the “Make in India” policy in 2014, followed by the Aatmanirbhar Bharat (“Self-Reliant India”) initiative in 2020, increasing opportunities in the defense sector are bolstering the industry as a whole, and the rise of a burgeoning private sector aspect. The latter was aided by the release of a new military procurement defense offsets policy model - the Defense Acquisition Procedures (DAP) - in 2020, which raised the minimum level of local content in prioritized defense procurement categories from 40 percent to 50 percent, simplified rules to enable greater private sector participation in the process, and effectively blocked over 100 defense products from importation (this had grown to over 340 items by mid-2024).

The effect has been to spur overall domestic manufacture of defense goods, with production increasing by 17 percent from 2023 to 2024. Moreover, the share of private sector defense production grew by 38 percent from 2020 to 2024.

Still, India remains a significant weapons importer - the world’s second-largest behind Ukraine. And while the government hopes to push towards becoming a net exporter of defense material, that effort remains a ways off.

Despite notable advancements over the past 4-5 years, India’s defense sector - while growing and improving - still falls short of the goal of achieving 70 percent self-reliance in the equipping of its armed forces by 2030. The private sector still lags behind the many state-owned defense corporations (referred to as Defence Public Sector Undertakings, or DPSUs) in terms of competitiveness, many critical capabilities gaps - ranging from advanced avionics, stealth technologies, high-performance aircraft engines, and complex naval platforms - remain.

The Indian defense industry continues to be dominated by 16 DPSUs (headlined by Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd, Bharat Earth Moves and Bharat Electronics) and 52 laboratories overseen by the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO).

Conclusion

The defense industrial landscape of the Asia-Pacific is experiencing a fundamental transformation from an import-dominated market to one of growing self-sufficiency and export capability. This shift is not merely economic; it's viewed as a strategic imperative. The COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine underscored the fragility of global supply chains and the geopolitical pressure on nations to align with competing great powers. By fostering industrial resilience, countries can gain greater foreign policy flexibility and control over crucial sovereign decisions.

While achieving complete defense independence is a goal few nations will ever fully realize, building robust domestic capabilities and leveraging foreign acquisitions for technology transfer and infrastructure development provides a vital hedge. Therefore, nations will continue to invest in their local defense sectors, transforming the Asia-Pacific from a passive consumer of military hardware into a dynamic and influential center of global defense innovation and production.

This content is made possible by our sponsor General Atomics Aeronautical Systems; it is not written by and does not necessarily reflect the views of Defense One editorial staff.

NEXT STORY: Turning data overload into mission advantage