MOHD RASFEAN / THE ATLANTIC

The Final Pandemic Surge Is Crashing Over America

For the first time, the U.S. recorded 1 million COVID-19 cases in one week.

Understanding the pandemic this week requires grasping two thoughts at once. First, the United States has never been closer to defeating the pandemic. Second, some of the country’s most agonizing days still lie ahead.

Long term, the view has never looked brighter. This week, confirmation came that scientists have developed two vaccines against the coronavirus, each at least 90 percent effective, and more shots are likely on the way. Some health-care workers could be vaccinated by New Year’s. Most Americans can expect to receive a shot in the spring, according to Anthony Fauci, the country’s top infectious-disease expert.

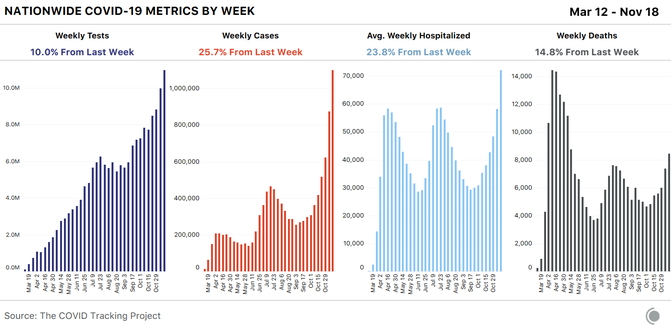

Yet in the short term, the outlook is unavoidable: The country faces several weeks of mass suffering and death. Almost every major metric of the pandemic stands at or near record levels, according to data collected by the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic.

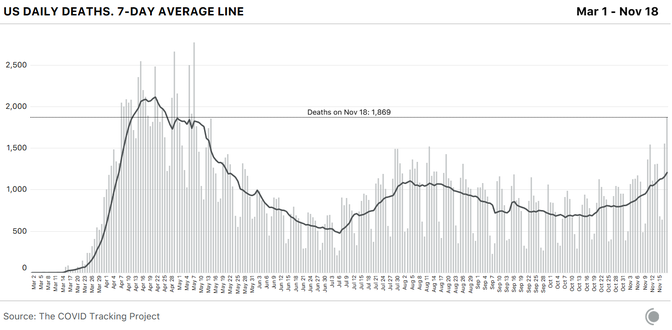

More Americans are getting sick: The U.S. has recorded more than 1 million cases of COVID-19 in the past seven days, the highest level ever. More Americans are in need of urgent medical care: Nearly 80,000 Americans are in the hospital with COVID-19 right now, smashing the old record of 59,924. And more Americans are dying: At least 8,461 people have died of COVID-19 since last Thursday, the highest seven-day total since May.

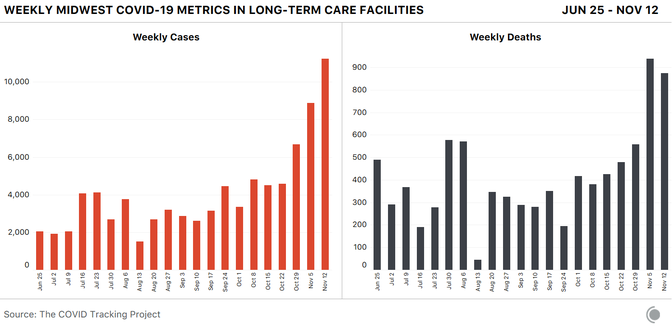

More older Americans, and residents of nursing homes, are also getting sick. This week, nursing homes and similar facilities reported 29,606 new virus cases among residents and staff, the largest increase in six months. This surge is especially foreboding because the virus is deadliest in these places; about 40 percent of all U.S. coronavirus deaths have happened in long-term-care facilities. For weeks, White House officials have argued that the virus should be allowed to spread freely as long as nursing-home residents are protected. The new data make clear that this approach is failing.

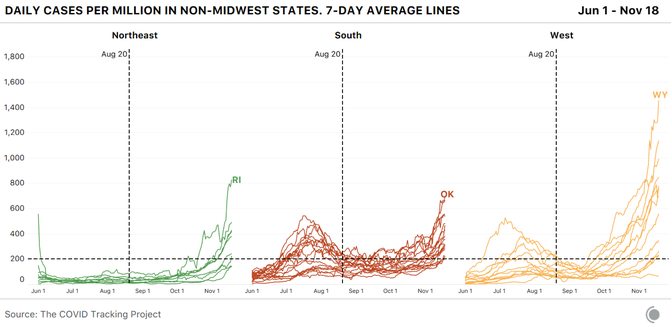

The virus continues to hammer every region of the country. Fifteen states hit all-time records for new cases this week. Five of those record-breaking states are in the Northeast; no state in that region had set a new case record since May 31.

In short, the United States is plunging into what may be the darkest period of the pandemic so far, even as it lacks the public-health orders or congressional assistance that buffered it in the spring. Because the virus is so widespread, America’s medical system is facing a greater test now than it did then; one in five hospitals nationwide reported a staffing shortage this week, according to federal data.

A vaccine is at hand. But for tens of thousands of Americans, it will come too late.

Here are five big lessons from the data we collected this week at the COVID Tracking Project.

First: Cases are increasing exponentially nationwide, and it may be months before they fall in some states.

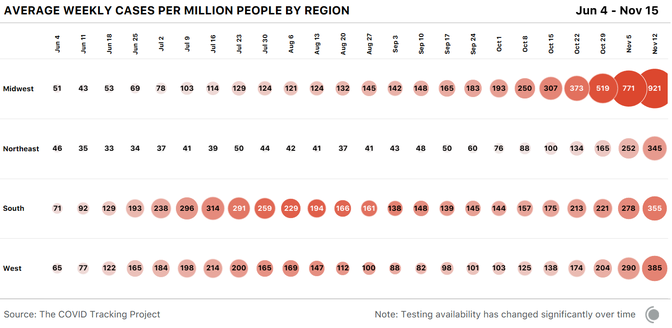

For the past few weeks, outbreaks have been worsening rapidly in more densely populated midwestern states like Illinois and Michigan. At the same time, cases have been steadily rising in every region of the country. Nationally, the seven-day average for daily reported cases has almost doubled since November 1.

But what does it mean to see the country report 1 million cases in a single week? Leaving aside that this number accounts only for detected cases—true infections are almost certainly higher—we know this wave of newly diagnosed cases will crash into hospital systems that are, in many areas, already over capacity. And we know that three or four weeks behind each jump in cases, we expect to see a spike in reported deaths.

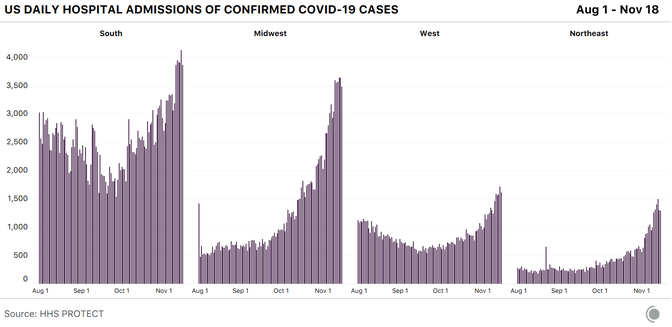

Ominously, this effect might be hitting multiple regions at once. Cases in the South have grown closer to that region’s summer peak, while the Midwest continues to post enormous increases and the West and Northeast creep upward.

This increase in cases can’t be chalked up to testing. While our national expansion in testing has seen the number of tests rise linearly, cases are now growing exponentially. In fact, the testing infrastructure may be coming under strain again, as it did during earlier outbreaks. News organizations are once again reporting long lines at drive-through COVID-19 testing sites, and Quest Diagnostics, which makes both PCR and antigen tests, this week said high demand and limited supplies are delaying the delivery of some results. Data reporting, too, is increasingly difficult as case numbers soar, case investigations and contact tracing even more so. And at the moment, we don’t see any indications that cases have reached a peak nationwide.

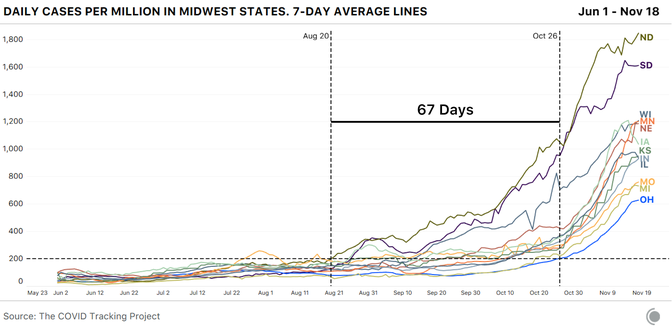

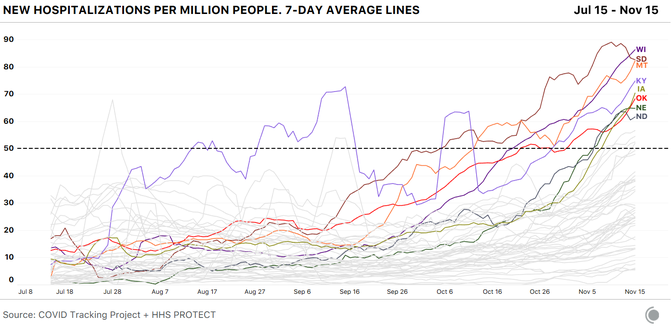

Nationally, cases have already been rising for 10 weeks. Yet based on what we’re seeing in the data, the outbreaks in many states, even in the hard-hit Midwest, may have plenty of room to grow. Look to North Dakota, for instance, where cases started taking off almost exactly three months ago. (For our purposes, we define the beginning of a surge as the moment when a state sees an average of more than 200 new cases a day per million residents.)

North Dakota passed that line and began to surge on August 18. But another 67 days elapsed before every other state in the Midwest had followed it. As of today, North Dakota is a canary in the coal mine for our current outbreak: It has reported more new cases per capita than any other state or territory for nine of the past 11 weeks. But it’s not clear that North Dakota’s outbreak has even peaked yet. Some states in the region have taken more aggressive public-health measures than North Dakota, and they may see declines soon. But among those that have adopted a similar approach to the virus as North Dakota, we could be looking at many more weeks of rising cases.

A similar story is unfolding across the country. Only three states have kept their average case totals below that “surge” threshold of 200 daily new cases per million residents. Yet many states just crossed that threshold and are steadily rising now. If those states follow the same path as the Midwest, they could more than triple their case counts in the coming weeks.

Where race and ethnicity data are available, we are seeing cases rise most quickly for Indigenous and white populations in many states. Not all states report data for Indigenous people; of those that do, 18 now report more than 1.5 times the number of cases reported a month ago. In eight states, the number of reported cases for white people has more than doubled over the same time, while cases have grown more slowly in other racial and ethnic groups.

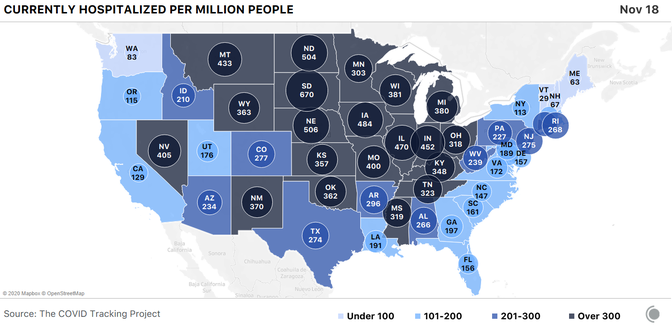

Second: Hospitalizations are also smashing records nationwide, and the national medical system is under the greatest strain it’s faced in the pandemic so far.

As we have written many times before, it’s clear that increases in COVID-19 cases mean more reported hospitalizations about 12 days later, and more reported deaths within a few weeks. In human terms, some of the people being diagnosed now will end up sick enough to be admitted to a hospital. Some of those people—though far fewer than in the spring—will die. The gains we’ve made since the spring in keeping people alive with severe cases of COVID-19 are at risk if our hospital systems are overtaxed. And our hospital systems are already overtaxed, even before the huge case spikes we saw this week and last week have converted into rising hospitalizations.

This week states reported a 21 percent increase in the number of patients hospitalized with COVID-19; that figure has risen 67 percent since November 1. The number of people hospitalized per capita in the Midwest has hit a level not seen since the spring surge in the Northeast.

Our colleague, Alexis C. Madrigal, wrote at The Atlantic this week about the dire straits facing American hospitals; 22 percent of facilities told the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services they expect staffing shortages. The examples are everywhere: More than 900 staff at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesotaand Wisconsin have been diagnosed with COVID-19 in the past two weeks; El Paso’s convention center has been converted to a field hospital, and some hospital patients are being sent as far as Austin, nearly 600 miles away, for treatment.

Using the data we compile from state and territorial health departments, we have been able to track total current COVID-19 hospitalizations, but not newly admitted COVID-19 patients—a more precise measure of where outbreaks are worsening. A newly released dataset from the Department of Health and Human Services allows us to look at daily COVID-19 admissions of new patients, and they are rising sharply in every U.S. region.

A per-capita view of hospital admissions data also allows us to pinpoint states both inside and outside the Midwest that are seeing spikes in new hospitalizations. It’s clear that Wisconsin is still in serious trouble and that Montana’s new admissions are rising sharply, while South Dakota’s may have peaked. Iowa, Kentucky, and Oklahoma are all showing the signs of dangerous increases in new patient admissions as well.

Third: Deaths may soon exceed their levels from the spring.

States reported more deaths from COVID-19 this week than we’ve seen since May. Yesterday, The New York Times reported that the COVID-19 pandemic has claimed 250,000 lives. As we wrote the last time a similar record loomed, our current figures run behind those of several other sources because we compile data at the state level, rather than from counties or cities. As of November 18, the COVID Tracking Project recorded 241,704 fatalities from COVID-19.

Our understanding of who is dying is hampered by states not reporting demographic categories consistently. Reported deaths for white people are still proportionately lower than for most other demographic groups, but the trend is shifting. In many states, deaths are rising most quickly among white residents. Six states are reporting more than 1.5 times the deaths among white residents as in mid-October, while deaths have generally risen more slowly in other racial and ethnic groups.

Fourth: The virus has continued to ravage long-term-care facilities.

As our long-term-care update detailed earlier this week, nursing homes and other congregate care facilities reported their largest increase in cases in the past six months—29,606 cases. New COVID-19 cases in nursing homes, assisted-living facilities, and other long-term-care facilities rose 20 percent across the nation.

From the 37 states that report residents and staff separately, we know that residents account for twice as many cases as staff. Yet, from the same batch of states, we know that less than 1 percent of deaths in long-term-care facilities occur among staff. There are still 13 states that don’t split resident and staff cases and deaths, obscuring any additional analysis.

After three weeks without releasing cumulative long-term-care case data, North Dakota’s health department sent us a spreadsheet on November 17 that shows substantial increases in cases. Resident cases have increased by 70 percent and staff cases by 61 percent since October 29. With a three-week gap in the data, we are unable to determine at what rate cases are increasing.

After a delayed weekly update due to dashboard adjustments, West Virginia’s devastating uptick in long-term-care cases and deaths recently became apparent with their updated cumulative totals. In the past two weeks, deaths related to long-term-care facilities have more than doubled. Cases very nearly did the same. In two weeks, COVID-19 spread across West Virginia’s long-term-care facilities as much as it had in the entire eight months before. With COVID-19’s capacity to exponentially increase, West Virginia’s increases indicate a likely tragic coming weeks.

Finally, the country’s public-health response remains scattered and patchwork. But some Republican leaders have urged mask use in recent days.

Facing rising cases and hospitalizations, many states and metropolitan areas recently mandated new or more stringent measures in an effort to contain the virus. California Governor Gavin Newsom said he was pulling an “emergency brake” for the state, eliminating indoor dining, closing indoor gyms, and banning indoor worship services in 41 counties, among other efforts. Iowa, a state whose governor had long resisted a mask mandate, announced it would require residents to wear masks. Minnesota’s governor banned indoor dining and in-person get-togethers until mid-December. New York City this week said it would shut down schools as cases have risen. Governor Mike DeWine of Ohio, who was one of seven Democratic and Republican governors to co-author an opinion piece in The Washington Post this week urging Americans to cancel Thanksgiving, advised residents to wear masks and instituted a curfew. Costco, one of the nation’s largest retailers, said customers would be required to wear a mask while inside its stores, regardless of local and state regulations.

This week, West Virginia Governor Jim Justice tightened the state’s mask mandate and held an 80-minute press conference in which he implored West Virginians to get on board. “I love all of our kids, and I want them to be able to play ball and go to school, but more than anything I want us to get more control over this terrible virus that’s just eating us alive,” said Justice, a Republican. “I want us to absolutely wear a mask. I will not allow people to just decide they’re not going to wear a mask. I mean, what right do they have to infect others or possibly infect others? … Ninety-six percent of the people in West Virginia believe we ought to be wearing masks. I strongly urge—strongly urge—us all to wear a mask. That’s all we’ve got to go on right now.”

Artis Curiskis, Alice Goldfarb, Erin Kissane, Jessica Malaty Rivera, Kara Oehler, Joanna Pearlstein, and Peter Walker contributed to this analysis.

This story was originally published by The Atlantic. Sign up for their newsletter.