In this June 22, 2016, file photo, a Border Patrol agent walks along a border structure in San Diego, Calif. AP Photo/Gregory Bull

Toward the end of September, Ramon Antonio Monreal Rodriguez obtained $650,000 worth of cocaine from smugglers along the Arizona border. The 32-year-old Tucsonian made two exchanges of drugs and money over the course of two nights, and ensured 41 kilos of coke got into the US from Mexico without any problems.

Monreal and the traffickers met up at a prearranged spot in a patch of desert near the San Gabriel Gate. Monreal knew the area well. After all, he had been working in the vicinity since he joined the US Border Patrol a decade earlier.

The FBI, which had Monreal under surveillance, arrested him on Sept. 25; Monreal resigned from his role as an agent later that day. According to federal court documents, he was on duty and driving an official Border Patrol vehicle when he made both exchanges and received $66,230 and three kilos for his trouble. Monreal, whose arrest was first reported by Curt Prendergast of the Arizona Daily Star, is also facing weapons charges for allegedly buying guns illegally for two other people.

Records obtained by the Project on Government Oversight reveal that 13 US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) employees have been arrested in the past two years; Monreal is the fifth so far to be brought up on drug-related charges. In recent years, others have jeopardized their careers for sex, cars, homes, and hot tubs.

Related: Homeland Security Warns Its Employees of Increased Threats to Them

Related: How Corruption Undermines NATO Operations

Related: Ukraine Is Losing Fewer Weapons to Theft, but High-Level Corruption Persists

For any law enforcement agency, hiring the right people and supervising them properly are crucial. Yet, CBP and its Border Patrol division have fallen short in both of those areas, according to former officials as well as CBP’s own internal reviews.

A 2015 report from an internal audit by a CBP corruption advisory panel suggested that corruption-related arrests of CBP personnel “far exceed, on a per capita basis, such arrests at other federal law enforcement agencies.” James Tomsheck, a former head of internal affairs at CBP, tells Quartz that the picture “could be far worse than what the arrest stats show.”

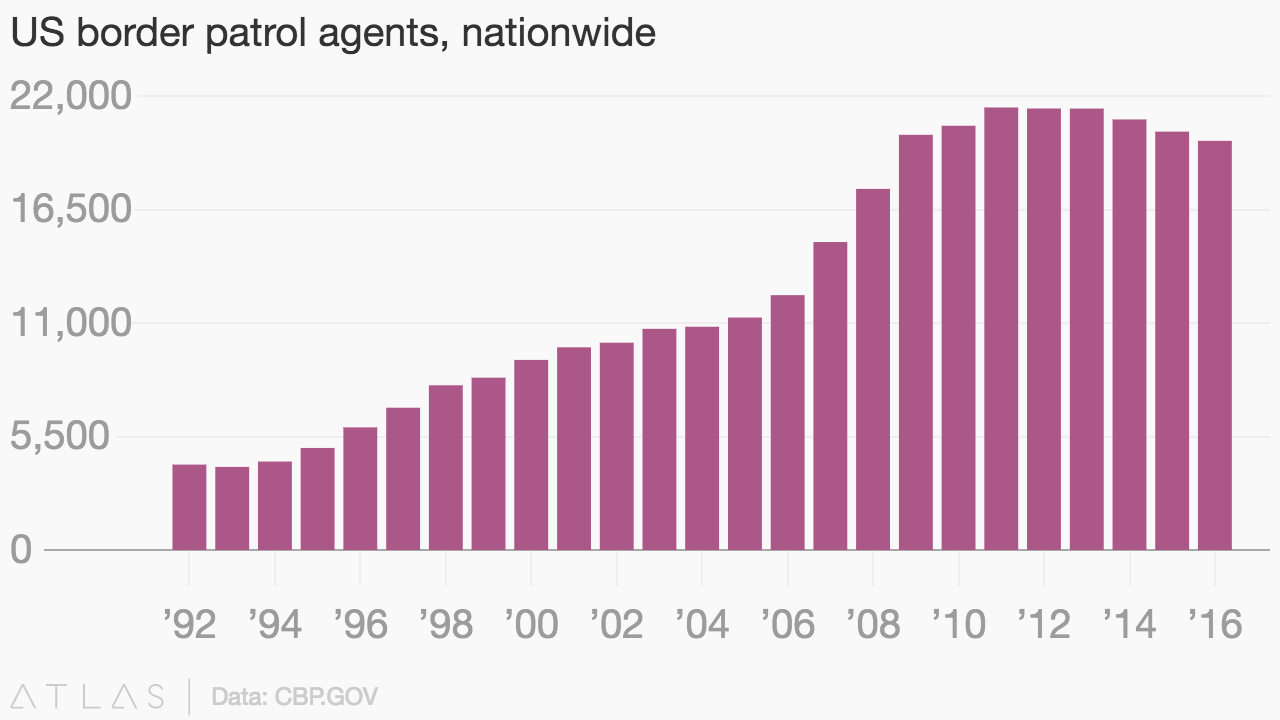

An ill-advised initiative to swell the ranks of Border Patrol agents in the mid-2000s was accompanied by an extraordinary spike in misconduct within the agency. Now, the Trump administration is looking to implement another hiring surge.

Last year, an executive order from US president Donald Trump ordered the Border Patrol, which has just under 20,000 agents, to hire 5,000 brand new ones as “as soon as is practicable.” Congress declined to fund the surge, but the CBP has pressed ahead with plans to expand its headcount. It awarded Accenture a contract worth just under $300 million to help with recruiting and hiring.

A spokesperson for CBP tells Quartz that any “decision to change any aspect of the hiring process should not result in the erosion or lowering of agency standards. All successful applicants must still pass a polygraph examination, strenuous vetting checks, and the highest level of background investigation available, in addition to still undergoing basic training at our Academies. We are confident that our recruiting and hiring processes are exceptionally strong.” But precedent doesn’t bode well.

When the CPB similarly ramped up hiring in 2006, under US president George W. Bush, standards were lowered in order to hire about 8,000 additional agents by 2009. It was in that time that Monreal was hired. To speed up the recruitment process, background checks on candidates were abbreviated and sometimes not done at all. The training period for new agents was shortened. And according to the Associated Press, “the number of employees arrested for misconduct, such as civil rights violations or off-duty crimes like domestic violence, grew each year between 2007 and 2012, reaching 336, a 44-percent increase.”

The race to ramp up

Ramon Monreal was given a gun and a badge in 2008.

That was the same year that Tomsheck, who ran internal affairs at CBP from 2006 to 2014, realized the surge in hiring “had gone awry and there were significant problems,” as he told the AP last year.

A 2012 report by the US Government Accountability Office said the 2006-2009 hiring surge drew an unknown number of recruits from the criminal underworld who applied for—and received—jobs as border agents and officers “solely to engage in mission-compromising activity.”

CBP and Border Patrol began phasing in pre-employment polygraph testing in February 2008, Tomsheck tells Quartz. “The results were astounding,” he says. For starters, he says, potential recruits were failing the lie-detector tests at a rate of 55%. (The failure rate is even higher now.) And according to Tomsheck, more than 30 people confessed to having applied for a position at someone else’s direction, including that of drug traffickers. “They very clearly were infiltrators being placed within the ranks to be the eyes and ears of criminal organizations,” said Tomsheck.

A spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security, the agency that houses the CBP, told the Project on Government Oversight that CBP “has taken many steps to increase accountability and transparency,” and that background checks “are much more robust” than they were 10 years ago. The Anti-Border Corruption Act of 2010 mandates, among other things, that all new recruits pass a polygraph exam—although the House of Representatives introduced a bill in June to waive this requirement in an attempt to streamline the process. The US Senate has not yet voted on the measure.

As of May 1, all Border Patrol and CBP candidates are given a polygraph exam called the Test for Espionage, Sabotage, and Corruption, or “TES-C.” An August CBP press release touting the success of a pilot program involving the TES-C polygraph said that the format “reduced average exam times [and] the number of retests” while revealing “no appreciable difference in exam efficacy” compared to the more cumbersome Law Enforcement Pre-Employment Test (LEPET), a standard polygraph format used previously by the agency.

However, according to Tomsheck, who spent 23 years in the US Secret Service before joining CBP and says he was directly involved in implementing polygraphs for Secret Service pre-employment screening, TES-C is less effective than LEPET for the task at hand. LEPET was developed by the Secret Service in conjunction with the psychology department at the University of Utah and became the standard for screening federal law enforcement officers, Tomsheck says. TES-C, he says, is geared toward testing intelligence officers.

TES-C was developed by the Office of Professional Responsibility, which is part of the US Justice Department, and a federal institution called the National Center for Credibility Assessment (NCCA). According to CBP, the new test “combined an approved NCCA counter-intelligence scope testing format with suitability topics found in the LEPET format that are relevant to CBP’s law enforcement mission.”

Tomsheck tells Quartz the newer test “is almost certain to create false negatives for persons that are unsuitable and would be found unsuitable by the correct polygraph test. They’re degrading personnel security protocols to accommodate a hiring initiative in a way that is almost certain to degrade security at the border instead of enhancing security at the border.”

Safeguards aren’t working

Monreal appeared in court for a preliminary hearing on Nov. 6. His lawyers, federal public defenders Elizabeth Lopez and Christina Woehr, did not respond to a request for comment. A woman who answered the phone at a number listed for Monreal in public records and gave her name as “Marna” said Monreal was not willing to comment on the case.

While the vast majority of agents and officers stationed at the border are upstanding and honest, enough of a problem exists that the FBI maintains a dedicated Border Corruption Task Force. According to a 2015 internal audit by a CBP corruption advisory panel co-chaired by former New York City police commissioner Bill Bratton, corruption “is the Achilles heel of border agencies…There are major drug trafficking and smuggling organizations—transnational criminal organizations that operate on both sides of our borders—that have budgets in the tens of millions of dollar for bribes and corruption of government officials.”

The advisory panel also described CBP’s Office of Internal Affairs as “woefully understaffed.” It said that an “inadvertent, unintended consequence” of a reorganization at the Department of Homeland Security meant the CBP division suddenly found itself with “no internal affairs investigators” on March 1, 2003. ”CBP has had to rebuild its internal affairs capability, but it is still far below what is needed,” the panel concluded.

Staffing needs

The Border Patrol faces a current attrition rate of at least 6% a year, which means it would need to hire more than 1,800 agents just to net an additional 500. To net 5,000 new agents, as Trump had requested, for a staffing total of 26,370 agents, CBP commissioner Kevin McAleenan has estimated the Border Patrol would need 2,729 new recruits annually for five years.

Is it a realistic target? In a memo obtained last year by CNN, McAleenan noted that in fiscal 2016, the CPB hired 485 Border Patrol agents, and that was with “aggressive recruitment efforts and hiring process improvements.”

Meanwhile, apprehensions of migrants at the US southwest border have fallen by more than half since 2006.

In the face of this, Tomsheck believes rushing to add thousands of new Border Patrol agents to the ranks as quickly as possible is little more than a piece of political theater that’s doomed to fail.

“I guess the phrase, ‘We’ve seen this movie before,’ applies,” he says.

NEXT STORY: Trump's Space Force Faces an Uncertain Fate