Nanosatellites could provide future battlefield communications

The Space and Missile Defense Command is testing small satellites that could deliver over-the-horizon voice, data and imagery.

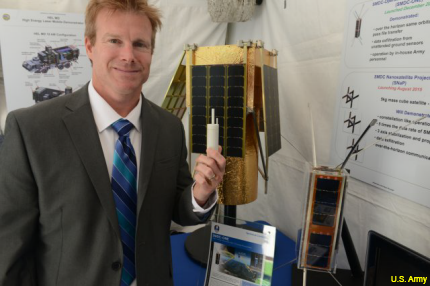

Dr. Travis Taylor holds a plastic rocket engine in front of the SMDC-ONE, at right, and the larger imaging satellite.

Over-the-hill visibility is a valuable asset for troops in the field, but it’s not always available, especially in remote areas. The Army may soon be able to get around that problem by giving soldiers access to a new kind of eye in the sky—small, inexpensive nanosatellites that can provide voice, data and even visuals.

The service’s Space and Missile Defense Command - Tech Center, or SMDC, has developed and tested a nanosatellite that provides voice and data, called the SMCD-ONE (Orbital Nanosatellite Effect), and is developing an imaging satellite that would work the same way.

The first SMDC-ONE is in orbit now, and the tech center is planning to launch three more this year, with an as-yet undetermined number to be launched in 2016. "It's basically a cellphone tower in space, except it's not for cellphones, it's for Army radios," said Dr. Travis Taylor, the senior scientist in the center’s Space Division, who talked about the satellites at this week’s DOD Lab Day at the Pentagon.

The satellite, in the shape of an oblong box maybe a foot long, can connect dismounted soldiers to a forward operating base or to sensors in the area. It was designed, starting in 2008, to last a year or longer in orbit and cost no more than $350,000 each, according to Ducommun Miltec, which developed the satellite. (PDF) Miltec delivered eight of the satellites to SMDC in 2009 in advance of the current orbital tests.

SMDC-ONE nanosatellites could be joined in space by larger (but still considered nano) imaging satellites, the first of which the Army plans to launch on a test flight in February from the International Space Station. That satellite, still unnamed, will have a ground resolution of two to three meters, enough to identify a tank or truck. “This is capability the Army doesn't have right now," Taylor said.

It will require some manual work, since the imaging satellite will only be able to process one image at a time. The example Taylor gave was of a squad leader requesting an image of an area nearby from a brigade’s base, where someone would have to give the request priority. He said the satellite could process an image in about a minute.

Although still in the demonstration phase, Taylor said he hopes the tests will be successful enough to create the demand for a full constellation of them. "If we put five to 12 of these small satellites in orbit, it will cover most areas soldiers are operating, providing them real-time, all the time" communications, he said.

A key to the project is positioning the satellites, which will be in low-Earth orbit. Nanosatellites wouldn’t be launched individually, but would hitch rides with larger satellites and be deployed once in orbit. That doesn’t guarantee it will be in the right place—the host satellite has its own orbit to follow—so SMDC developed a small, plastic device that serves as an engine. "This is an actual rocket motor, made from a plastic printer," Taylor said. "Inside is liquid nitric oxide and a sparker—just like a barbeque lighter inside—so the nitric oxide combusts with the plastic" when the sparker is fired. "That's your rocket fuel. Then you have a very good rocket motor."

Taylor said if the current tests prove the values of the technology, they could be deployed for use in three to five years.

NEXT STORY: Air Force to certify SpaceX for launches by June