Air Force F-35A Lightning II aircraft assigned to the 388th Fighter Wing and 419th Fighter Wing participate in an exercise at Hill Air Force Base, Utah, Jan. 6, 2020. R. Nial Bradshaw, Air Force

Why Does the US Spend So Much on Defense?

It is well to remember that the real bill includes not just DOD spending but VA, intelligence, and more. But those who would cut spending must also propose a new strategy.

It is common in nearly every election cycle for at least one candidate to claim that the United States spends too much on defense. Elizabeth Warren said it last year in a Foreign Affairs article, Bernie Sanders in a Vox interview, and we are likely to hear it again as the general election approaches. Unfortunately, these claims almost always fail to explain just how much America spends on national security, why it traditionally spends so much, or what a major budget cut really entails.

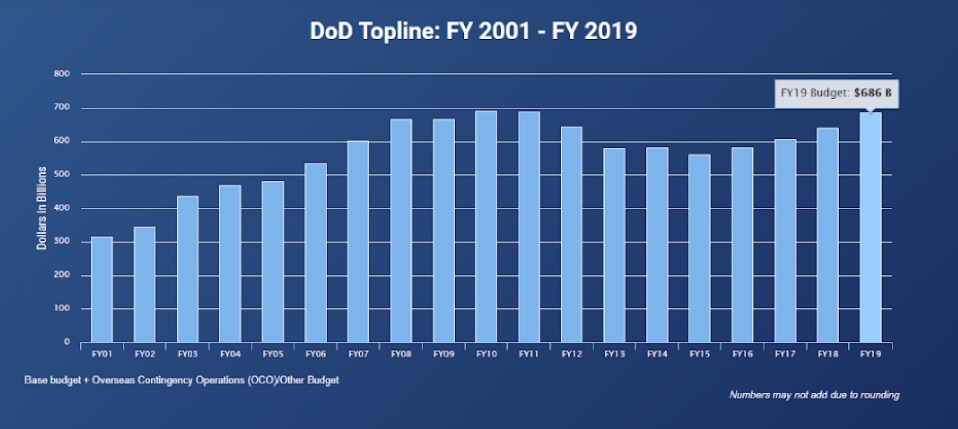

Yes, the United States spends a lot on defense. Probably even more than you think. In fiscal 2019, the Defense Department’s budget, plus money appropriated for nominally unanticipated operational expenses, was $686 billion. A DOD chart shows that amount as part of a trend of generally rising budgets since the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, with some reductions after drawdowns in Iraq and Afghanistan began.

To put U.S. military spending in context, it is useful to compare what it spends to that of others. In fiscal 2018, the Defense Department’s budget of $649 billion — not even counting the contingency fund — was larger than the combined spending of the next seven largest militaries: $609 billion (China, Saudi Arabia, India, France, Russia, UK, Germany).

As large as the DOD budget is, the total amount spent by the United States on national security is actually much higher. The largest chunk outside DOD is spent by the Department of Veterans Affairs, which cares for former troops injured in past conflicts and funds the pensions of military retirees. The VA spent $201 billion in 2019, topping $200 million for the first time but not the last; the 2020 request was $220.2 billion. Adding the VA’s budget brings total national-security spending to $887 billion.

America’s nuclear weapons and naval reactors are maintained not by the Pentagon by the Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration, which also works to counter proliferation and nuclear terrorism. Adding NNSA’s $15.2 billion makes the total $902.2 billion.

It would be remiss not to include the intelligence community, or IC, though this can be a little complicated. The Director of National Intelligence makes public the combined unclassified budgets of the 17 agencies that make up the community. In 2019, that was $81.7 billion. This figure includes $21.5 billion for the Military Intelligence Program (funded by DOD and therefore not added to our burgeoning tally) and $60.2 billion for the National Intelligence Program, which covers non-military organizations such as the CIA. We don’t know how much the Pentagon kicks in for the National Intelligence Program; it could be up to $60.2 billion.

Therefore, America’s true total spending on national security in 2019, when including the DoD, VA, NNSA, and some portion of the IC’s non-military intelligence program, is probably between $902.2 and $962.4 billion. And yet this total does not include domestic security elements such as the Department of Homeland Security (2019: $72.3 billion) or the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Related: Esper Is Attempting the Biggest Defense Reform in a Generation

Related: Lawmakers Question Pentagon’s Use of ‘Slush Fund’ to Skirt Budget Caps

Related: We Really Need to Fix the Federal Budget Process

So, why does America spend such large sums on defense?

America has global security commitments, lots of them

The United States has treaties obligating it to the defense of about 51 nations across four continents. Here is how that breaks down:

- 28 through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization which covers Canada and most of Europe

- 18 through the Rio Treaty that applies to most of Central and South America.

- Two through the ANZUS Treaty with Australia and New Zealand

- A bilateral treaty with Japan

- A bilateral treaty with South Korea

- A bilateral treaty with the Philippines

In addition to these treaty commitments, the United States also has close relationships with, clear security interests in, and in some cases troops deployed to nations with whom we have no formal treaty. Some of these include:

- Taiwan (While the U.S. recognizes that the island belongs to China, it opposes hostile resolution of the dispute between Taiwan and Beijing.)

- Israel

- Saudi Arabia

- Iraq

- Afghanistan

- Jordan

- United Arab Emirates

- Qatar

The U.S. military also frequently finds itself involved in operations in unexpected places, such as when it was called to oppose mass killings and genocide in Kosovo and Libya. Given its logistical reach and versatile capabilities, the military also tends to be involved in humanitarian operations: responding to the tsunami and nuclear reactor accident at Fukushima, earthquake relief in Haiti, containing Ebola in West Africa, etc. Finally, there is the broad expectation that the U.S. military will ensure the free flow of maritime trade globally, including key choke points such as the Strait of Hormuz, Strait of Malacca, and Horn of Africa.

These commitments would be cheap and easily fulfilled if none of the nations had threats to worry about. Unfortunately, that isn’t the case, so the United States needs to be ready to respond to a Russian attack on NATO’s eastern flank, a North Korean attack on South Korea, a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, or an Iranian attempt to close the Strait of Hormuz. And it may have to respond to multiple crises at once.

This broad range of potential missions also means that America must keep a force ready for anything from high-intensity state-on-state conflict to counterinsurgencies and police keeping. Its adversaries, however, have the luxury of focusing much of their efforts — training, procurement, doctrine, infrastructure, etc. — on preparing to fight just America.

The United States signed up to so many international commitments under the guiding philosophy that it would rather play away games than home games. If you don’t like sports metaphors, this is the idea that America is better off remaining engaged in the world and halting aggression early, rather than waiting for it to gather strength and strike the U.S. homeland. This was a major lesson U.S. leaders took from World War I and II. After the former, the United States withdrew to isolationism, but was dragged into the latter by war in Europe and Asia. By contrast, since WWII, America has been internationally engaged with forward deployed forces and, probably as a result or maybe just by coincidence, there has not been a war between major powers since.

Those commitments are far away

All those security obligations and expectations means the United States needs to be able to project force globally. Pushing military assets around the world is a lot more expensive than just protecting your own borders. It requires a logistical fleet that can move personnel and equipment over vast distances, and the ability to do so in hostile territory. For example, if there isn’t an airfield nearby, one must be brought in — cue the $13 billion USS Gerald Ford aircraft carrier. Having multiple security obligations around the globe also drives a need for information, hence the large U.S. intelligence budget.

While partner nations cover a portion of the costs of hosting U.S. forces, there isn’t much argument that if the U.S. military was redesigned from a global force to one focused exclusively on homeland defense, its budget would look quite different.

If it is in America’s interest, and the interest of much of the world, for the United States to remain globally engaged, then the question must be asked: how does the U.S. meet all those commitments and respond to international crises? There are multiple approaches to providing that security coverage, but the United States has developed a general preference for how to do so. America prefers to achieve its goals without suffering many casualties, and it does so by emphasizing information, firepower, and advanced technology. If the country hopes to take on a major power on their home turf and not take heavy losses, it helps to have a professional military with a technological and information advantage, all of which is expensive. This means that America chooses to spend treasure rather than blood.

To illustrate this preference, consider the two technological offsets America has pursued, and third offset strategy it is currently developing. The first offset used nuclear superiority to counter the Soviet Union’s advantages in conventional forces and geography in Europe. The second offset was developed in the 70s and 80s when the United States combined long-range precision guided munitions with satellite and communications technology in a new joint doctrine. This proved very successful against Iraqi forces in 1991 and again in 2003, but less successful against insurgents in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. The third offset hopes to create a new advantage, this time using advancements in information technology (artificial intelligence, big data, and human-machine interfaces) and directed energy weapons.

What would happen if we did away with all this and cut the budget?

Since it is impossible to run an experiment with two Americas in two worlds where one has a large defense budget and the other a much smaller one, we can never know for sure what would happen if the United States made major changes to its approach to international relations, defense strategy, and defense budget. An important point is that those things are linked. If America cut military spending without changing its goals, it is likely to end up with a force that is overextended and vulnerable to surprise and defeat. This means the United States would be increasing the risk of a conflict occurring and probably the casualties it would have to take to prevail – if it can prevail at all.

A more cogent argument for a sizable budget cut would entail an accompanying reduction in global commitment and ambition. In this case, the United States would need to think hard about where to draw its lines in the sand and scope the force to meet those more modest goals. This isn’t irrational, it made sense to withdraw from the Vietnam War, and many people argue the same about current long-standing wars in Afghanistan and elsewhere. Whenever America does that though, other powers step in to take up the security vacuum created. If the United States did this on a large scale to achieve sizable cost savings, it opens up a lot of breathing space for others to fill. While it would be nice if allies filled this space, so far it has been adversaries like Russia, China, and Iran who have grown their influence instead. This gets back to the question of where the United States would be on the spectrum between full isolationism and the global policemen. If America shrunk its goals and budget too much toward the isolationist side, there is always a risk that a hostile power will emerge and force America back onto the global stage in an expensive and high-casualty way. The risk is that the United States may not know what “too much” looks like in time.

Is America’s current level of defense spending even sustainable?

Yes. While the amount spent in absolute dollar terms is a lot, it is a historically small portion of America’s overall economy. The chart below is from the DoD budget request and shows that what the United States spends as a portion of national wealth is historically low. The graph shows high points during WWII, Korea, Vietnam, the Cold War, and operations in both Iraq and Afghanistan as well as today. At 3.1 percent of the economy, America is spending about the same as Columbia (3.2 percent), less than Saudi Arabia (8.8 percent) and Russia (3.9 percent), but more than China (1.9 percent) according to the SIPRI military expenditure database. To anticipate the valid point that this is only looking at the $686 billion DoD budget figure and not the full $900+ billion figure, the revised calculation is about 4.2 percent of the economy. Likewise, all the other figures in this baseline also need to be adjusted upward to account for the other non-DoD military spending of the day, as do the comparisons with other nations, so the conclusion that this is sustainable doesn’t change much. Watch out for China’s defense spending figure in the future, as their economy grows and if the percent of that economy devoted to defense increases, they will become a peer competitor in defense spending.

Calls for major budget cuts need to be part of a bigger discussion, not sound bites

In conclusion, those who say the United States spends too much may be surprised to learn what Washington actually spends far higher than they believed. Any serious discussion of dramatically cutting the budget, however, must consider America’s international strategy, approach to conflict, and the risks it is willing to take. Americans are able to pay for the current international strategy, goals, and means to support it. Furthermore, it appears that the U.S. public is willing to pay this price because the nation prefers that the cost be in billions of dollars instead of tens or hundreds of thousands of lives.

In a world that the 2018 National Defense Strategy describes as characterized by an erosion of U.S. competitive advantage, the proliferation of advanced weapons technology, and strategic competition by Russia and China, defense spending is more likely to rise than fall. Saying that the budget is driven by a military-industrial complex makes for a good sound bite on the campaign trail, but ignores the substantive strategy choices associated with a radical departure from U.S. security policy since WWII. Any candidate who wants to shrink military spending must also explain how that will be achieved and what it entails.

[Due to a production error, part of this text was omitted when it was originally posted.]