Mr. David L. Norquist, performing the duties of the U.S. deputy secretary of defense, speaks about the fiscal year 2020 defense budget during a press briefing at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., March 12, 2019. dod photo by u.s. army sgt. amber smith

2020 Budget Request Reveals Slow Shift Toward Great Power War

It will take some years before various futuristic weapons even begin to arrive.

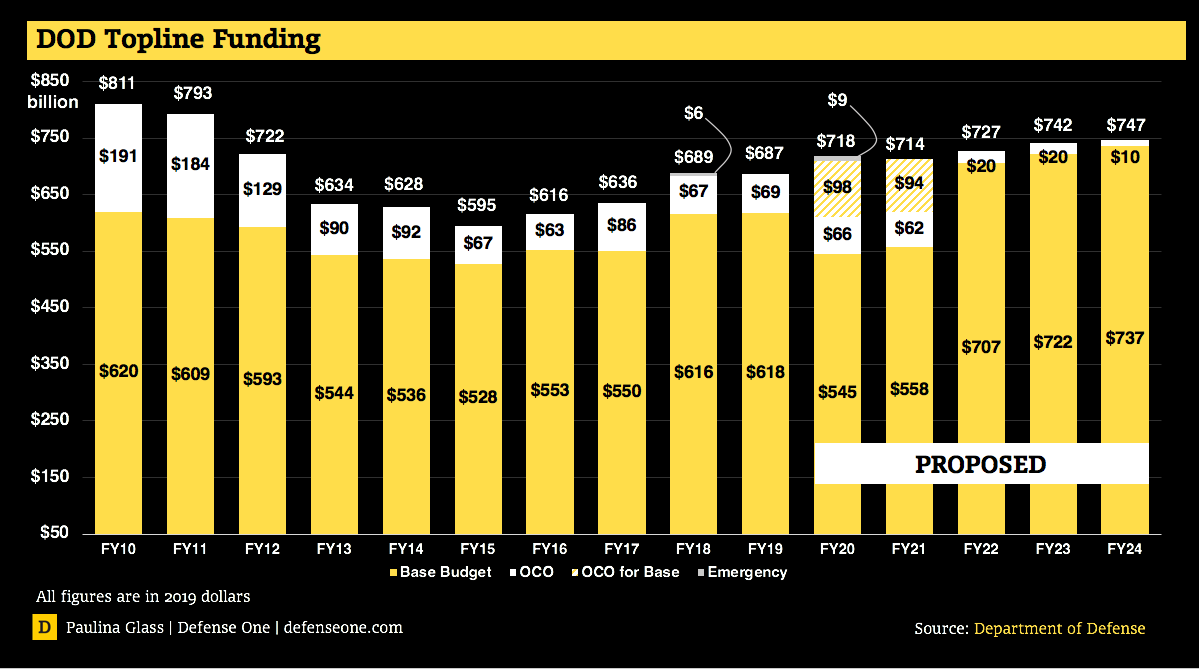

If there’s been one theme at the Pentagon since Donald Trump became president, it’s a desire to move fast, particularly when it comes to buying new weapons. The changes are necessary, officials argue, to keep pace with Russia and China, the two countries singled out as “great power” competitors in last year’s National Defense Strategy. Defense leaders urged Congress to allow the Pentagon to remove layers of bureaucracy in order to buy and develop new weapons faster.

But it will take much more time to mature new technologies and shift funding away from today's expensive weapons projects, which are strongly supported in Congress, to a new portfolio including killer lasers, hypersonic missiles and new generations of ships, combat vehicles and warplanes.

“[W]e must be prepared for the high-end fight against peer competitors,” David Norquist, the Pentagon comptroller, said as he presented the Pentagon’s fiscal 2020 budget proposal to reporters on Tuesday. Norquist has been serving as deputy defense secretary since Patrick Shanahan was elevated to acting defense secretary in January.

“Future wars will be waged not just in the air, on the land or at sea, but also in space and cyberspace, dramatically increasing the complexity of warfare,” Norquist said. “This budget reflects that challenge, pulling together all the pieces of the National Defense Strategy that have been built over the past two years.”

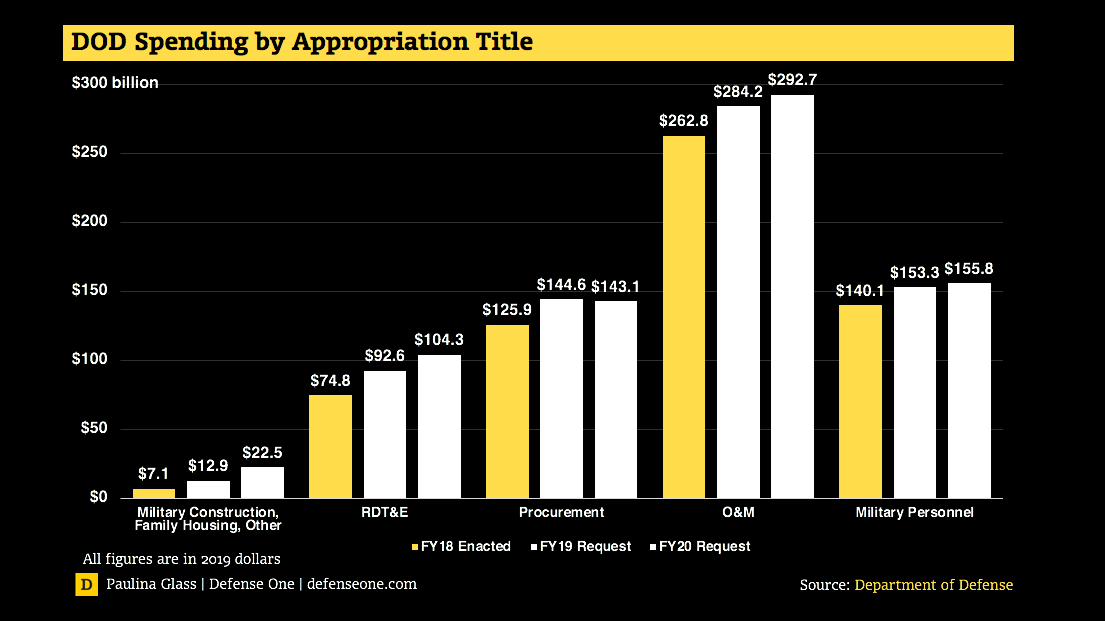

The Trump administration’s defense spending plan would shift focus, Norquist said, to space and cyber warfare; modernizing traditional weapons, like planes, ships, and armored vehicles; and new technology like artificial intelligence, hypersonics, and directed energy. The proposal has the largest research-and-development request in 70 years and the largest shipbuilding request in 20 years, Norquist said.

“The stakes are clear: If we want peace, adversaries need to know there’s no path to victory through fighting us,” he said.

Related: Is the Pentagon Truly Committed to the National Defense Strategy?

But many of the changes won’t happen for years, according to Army Undersecretary Ryan McCarthy. The Army is cutting or canceling 93 weapons, vehicle, aircraft, and other projects over a five-year spending period, know as the Future Years Defense Plan, or FYDP, so that Army officials can shift money into projects deemed critical to winning future wars.

“The choices of how these programs will be divested happen across the FYDP — towards the end of the FYDP — and you’re synchronizing them with the investment portfolios,” he said.

Related: Would a $700 Billion Budget Really Sink the Pentagon?

Related: Mattis ‘Optimistic’ Pentagon Will Get Needed Budget from White House, Democrats

Related: 2020 defense spending outlook: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯; Don’t forget the budget caps; more…

McCarthy pointed to the Army’s under-development Next Generation Combat Vehicle and Future Vertical Lift projects. Those projects are not supposed enter production for several years.

“As the funding lays in over time and you get through the modernization process, ultimately they synchronize towards the back end of this FYDP,” he said.

One challenge for the Pentagon is that it is still buying large numbers of ground vehicles to be used in counterterrorism or counterinsurgency fighting, in combat zones such as Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria rather than war with China or Russia.

For instance, the Army is “looking hard at the requirements … just how many” new Humvee-replacing Joint Light Tactical Vehicles it actually needs, McCarthy said. Add up the number of Humvees, Joint Light Tactical Vehicles and infantry squad vehicles the Army already owns and “we have well north of 100,000 vehicles,” he said. “We’re trying to hone in on the exact number of requirements of vehicles and that’s why the [JLTV] buy will be truncated over time.”

Big Tech Items

Trump is asking Congress for a bit more money for next-generation weapons of use in a potential war with China and Russia. The 2020 budget proposes a nearly 9 percent increase in the Pentagon’s research and engineering budget, which came in at $104 billion, or roughly $9 billion more than last year.

So what’s on the Pentagon’s new tech wish list? The Army, Navy, and Air Force are all building their own next-generation hypersonic missiles. That technology gets a bump in investment to $2.6 billion, up from about $2.4 billion enacted last year, said Michael White, assistant director for hypersonics. But the actual ask is some $10 billion over the next five years. A big portion of that will go toward testing, with the next flight test projected in about one year, according to White. Meanwhile, the Missile Defense Agency is asking for $157 million to develop satellites to better track and defend against enemy hypersonics (also part of the $2.6 billion request.)

One big item that stands out is $3.7 billion for “unmanned autonomous new tech.” That could include everything from next-generation fighter drones that fly alongside aircraft to new robot submarines. They figure heavily into the Pentagon’s expectations for future wars that will increasingly be fought by robots operating in environments that are thick with electromagnetic interference and missiles, and so will have to operate highly autonomously.

There’s a ton of new money for unmanned items. The Army will request $115 million for new “robotic development” versus $74 enacted last year. The Navy will request $21 million for an “advanced tactical unmanned aircraft system” versus $9 million enacted last year. There’s $54 million for core undersea unmanned tech, versus $ 27 million enacted last year; and some $68 million for large sub drones; up $8 million from last year. There’s $671 million for “unmanned carrier aviation” — read that to mean the new Tactically Exploited Reconnaissance node, or Tern, drone and others — versus $519 million enacted last year.

The Air Force budget for drones and unmanned tech is a bit more subtle. Funding for many individual unmanned programs is down compared to last year. But there’s a $1 billion request, versus $430 million enacted last year, for “next-generation air dominance,” which means so-called sixth-generation aircraft not yet in existence, in which pilots are optional. It also may include “wingman drones” and the like. Money for the new long-range strike bomber also jumped from $2.3 billion to more than $3 billion.

The president’s budget request separates autonomous and unmanned technology from “AI and machine learning.” The AI request is $927 million. About $200 million will go toward “Joint Artificial Intelligence,” which would include (but not be limited to) the new Joint Artificial Intelligence Center that the Pentagon is standing up to unify AI activities across the services. There’s also some $221 million requested for the follow-on to Project Maven, the Algorithmic Warfare Cross Functional Team, which is up from $131 million enacted last year.

Other missile programs would receive new research and development money. Among the key items to see big bumps is the Navy’s “precision strike weapons” at $718 million, versus $91 million enacted last year. The Navy is also bumping up its funding ask for the Tomahawk and the Tomahawk Mission Planning Center to $320 million, versus $252 enacted last year. The Air Force is pumping more money into the famous “ground based strategic deterrent,” basically ICBMs, some $570 million versus $414 million enacted last year. They’re bumping up their ask for the so-called “long-range standoff weapon” to $713 million versus $665 million enacted last year.

There’s some $9.6 billion for new tech in the “cyber domain,” which will include money massive new cloud programs.

The military will ask for $235 million in research into directed energy, which will include lasers and novel new technologies like neutral particle beams (energy moving slower than the speed of light,) and “implementing direct energy for base defense,” as well as scaling up high-power lasers and testing new ones.

The Army wants to put $12.2 billion toward its various modernization priorities. Including $115 million for “soldier lethality” such as guns, helmet-mounted targeting displays, and new munitions. They’re asking for $219 million for the next-generation combat vehicle; some $114 million for new command and control and communications and $74 million for new longer range rockets. Those priorities span several programs.

What the Defense Department budget request shows is that the Trump administration is choosing to spend federal dollars on military science and technology, but not necessarily science and tech more broadly. The president’s budget cuts $1 billion dollars from the National Science Foundation, bringing it down to about $7 billion.

NEXT STORY: New New START a Nonstarter: Russian Ambassador