A member of the U.S. Air Force stands near a Patriot missile battery at the Prince Sultan air base in al-Kharj, central Saudi Arabia, Thursday, February 20, 2020. Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/Pool via AP

Lessons from Yemen’s Missile War

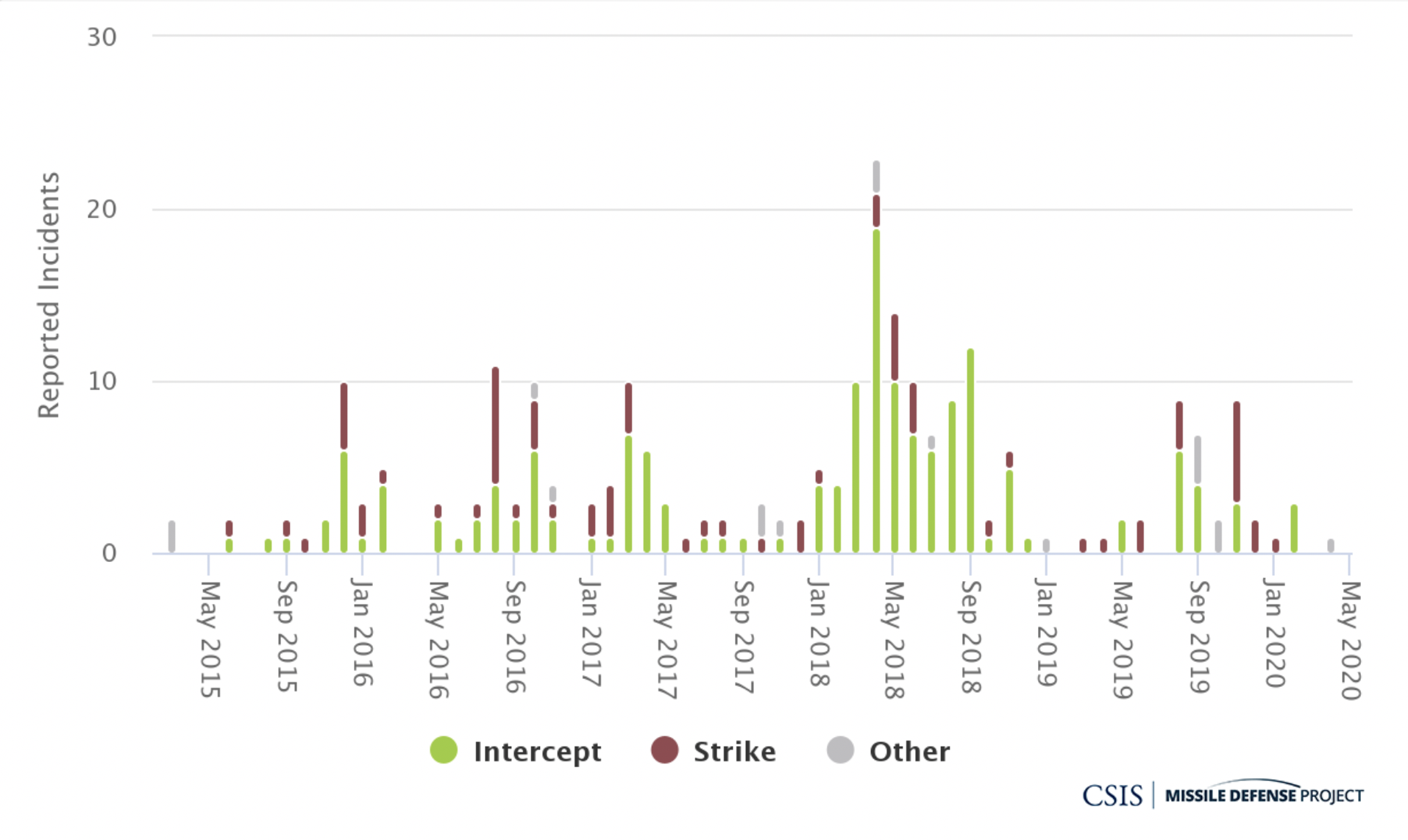

After five years, hundreds of long- and short-range missiles fired, and more than 160 missile-defense intercepts, it’s time to take stock.

At five years and counting, Yemen’s civil war is a remarkable case study in missile warfare, one that offers several critical insights for U.S. defense planners.

Since 2015, Iran-backed Houthi rebels have fired hundreds of ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and UAVs at Arab coalition forces and into Saudi Arabia, some reaching as far as Riyadh. Part of the Saudi-led Arab coalition’s response has been history’s most extensive use of ballistic missile defenses, with more than 160 reported intercepts.

This duel offers a rare glimpse into the utility and limitations of active missile defenses. It also provides insight into modern air and missile attack, the difficulties of destroying enemy missiles on the ground (“left-of-launch”), and the challenges of missile proliferation. The picture that has emerged is one in which the role of active missile defenses remains great, even when coupled with concerted counterproliferation and left-of-launch action.

The CSIS Missile Defense Project has been tracking missile activity in the Yemen conflict since 2015, with regular updates and interactive coverage in our online database.

After the ouster of President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi by Houthi militias in January 2015, Saudi Arabia led a coalition of Arab states to remove the Houthis from power and reinstate Hadi. From the onset, the Arab coalition was mindful of the threat posed by ballistic missiles, as much of Yemen’s prewar missile stockpile had fallen into the hands of Houthi fighters.

The Arab coalition began its intervention with an intense air campaign, a portion of which aimed to eliminate the Houthis’ ballistic missile capabilities. This initial effort met with only partial success, and later efforts proved even less effective. Intelligence on missile locations quickly became stale, and Houthi missile forces became better at evading detection. The frequency of coalition airstrikes against Houthi missiles declined significantly, while the number of Houthi launches rose.

Related: The War in Yemen and the Making of the Chaos State

Related: Who Is Paying for the War in Yemen?

Related: Yemen Cannot Afford to Wait

Iran has heavily supported the Houthi war effort. This aid has included increasingly advanced missiles, replacing pre-war stockpiles used up in the war’s early months. To block these transfers, the Arab coalition has restricted air, sea, and ground traffic into Yemen. It is impossible to measure how much these actions have reduced the the flow of weapons into Yemen. What is clear, though, is that significant quantities of Iranian missiles and other weapons continue to appear on the battlefield. What is more, the Arab coalition’s air and maritime restrictions have greatly worsened Yemen’s humanitarian crises by slowing the delivery of food and energy supplies and preventing Yemen’s sick from receiving medical attention abroad.

Given the shortcomings of its left-of-launch and counterproliferation efforts, the Arab coalition has leaned heavily on its Patriot air and missile defense forces to blunt Houthi missile attacks. Between March 2015 and April 2020, coalition air and missile defense forces reported at least 162 intercepts of Houthi ballistic missiles.

Arab coalition defenses have not been perfect, but available data suggests they have meaningfully limited damage from Houthi missile attacks and curtailed the value of Houthi missiles as a strategic tool. One illustrative data point is that at least four of the seven deadliest Houthi missile strikes took place in areas that lacked ballistic missile protection at the time of the strike. Given the damage seen in these unprotected areas, it seems likely that hard-hit areas, such as the border cities of Khamis Mushait and Jizan, would have experienced greater damage and loss of life had they too lacked defenses.

The geographic distribution of missile activity in the Yemen conflict since 2015.

The Yemen war also highlights the challenges to air and missile defenses. Today’s defenses face complex attacks from not just ballistic missiles, but also cruise missiles and drones. The Houthis’ increasing use of UAVs often frustrates existing air defenses, as these weapons’ small, low radar cross-section profiles can be difficult to distinguish from normal radar clutter. Their low-altitude flight paths also present a problem for missile defense radars, which are often calibrated to search for faster, higher-altitude missiles and aircraft. They also challenge air defense systems with sectored radars such as Patriot, as drones and cruise missiles can approach from any direction. The Houthis have used small drones to assassinate Arab coalition officers and attack energy infrastructure. They have also reportedly attempted to use drones to crash into Patriot radars on several occasions. If successful, such tactics could put a whole Patriot firing unit out of action.

The Arab coalition’s experience in Yemen’s missile war contains valuable lessons for the United States and its allies. It is difficult to imagine a future U.S.-involved war that would not be inundated with a wide variety of missiles. The Yemen missile war counterproliferation and left-of-launch interdiction does not negate the need for robust, right-of-launch missile defenses—even if the defenses themselves may be imperfect. Continued advancement in air and missile defense technology and operations will also be critical, however. Future wars will certainly feature aerial weapons that are more numerous, precise, and harder to detect than those wielded by the Houthis today.

For more, read the new CSIS report “The Missile War in Yemen.”

Don't miss: