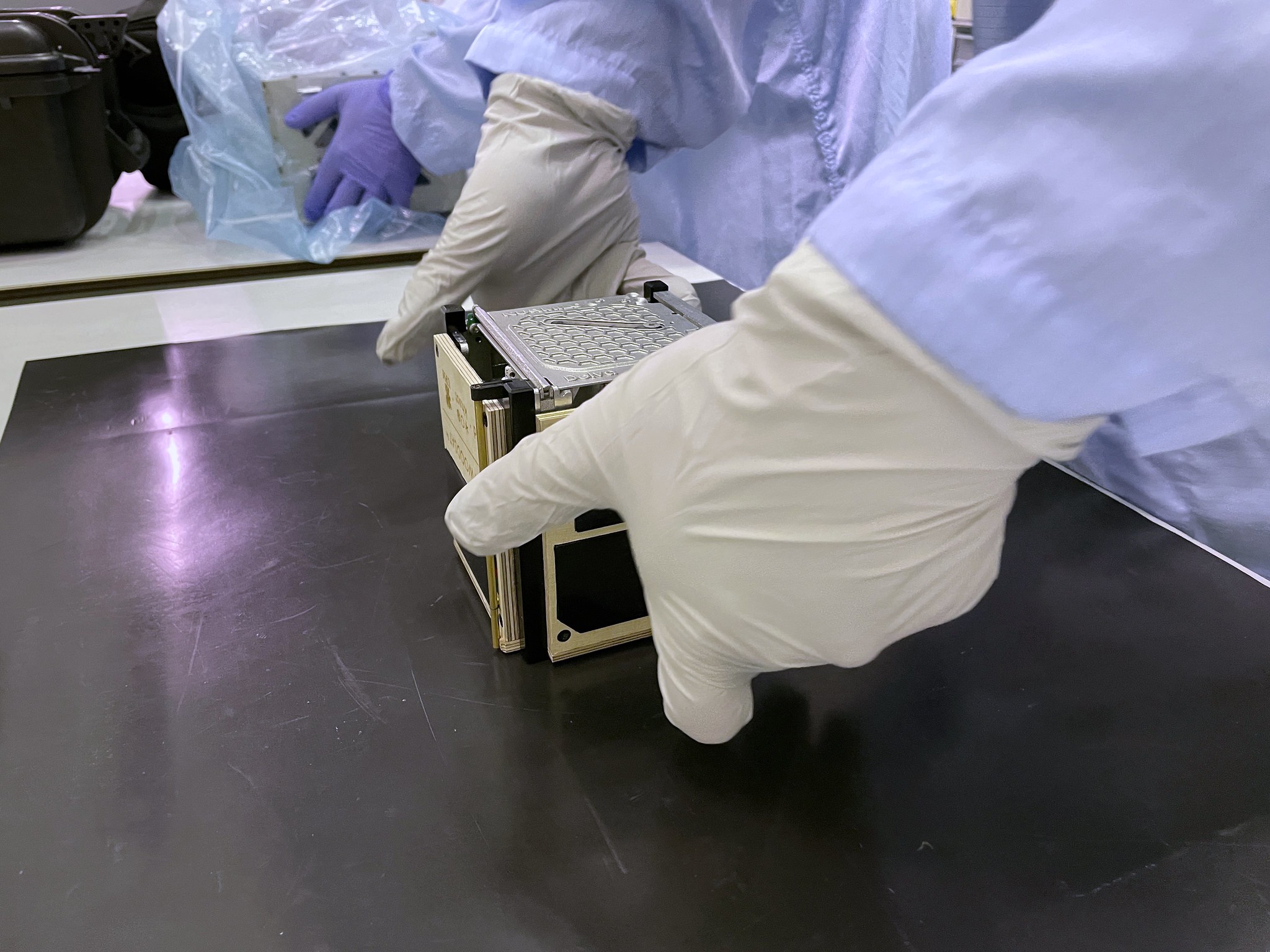

WISA Woodsat is the world’s first satellite using wood in its primary structure. It is made of WISA-Birch plywood, which is coated against strong UV radiation using a new atomic layer deposition method. UPM

Plywood Satellite Cleared for Space Launch

The WISA Woodsat could reduce space debris by using materials that will burn as they fall back into Earth’s atmosphere.

A tiny Finnish cubesat could make history later this year as the world’s first plywood satellite—and it will even have a selfie stick to record the moment.

The WISA Woodsat is being developed by Finland-based Arctic Astronautics, Ltd.; the European Space Agency, or ESA; and Finland-based forester UPM, maker of WISA plywood.

On July 9, after technical testing of the Woodsat’s birch-plywood outer shell, the ESA certified it for flight.

“The world’s first wooden satellite is now certified for a rocket ride and the final pre-launch phase can begin,” UPM said in a July 9 press release. The satellite is scheduled to launch into space from New Zealand on Rocket Lab’s reusable Electron rocket before the end of the year.

WISA Woodsat started as an idea in about 2015 by Arctic Astronautics chief strategy officer Jari Mäkinen.

“I started half-seriously to think about wooden satellite(s), because I've been doing wooden aircraft models, have been flying ‘real’ planes made of wood, and I have been involved with space technology since [the] 1990s,” Mäkinen said in an email to Defense One. “I felt that wood might be a good material, especially plywood.”

Plywood is a more environmentally friendly substitute for the Kitsat’s plastic outer casing, and a 2017 test flight balloon launch of a birch and birch plywood cubesat-sized box the company launched “mostly for fun” showed them that wood “and birch especially, supports surprisingly well the conditions of the upper atmosphere, almost like space,” Mäkinen said.

In addition, using plywood on a satellite launched into low-Earth orbit could mean that spent satellites would burn up after they lose power and begin to fall back to Earth—so the satellite wouldn’t end up adding one more piece to the thousands of pieces of space debris orbiting the planet.

Tracking those 32,000 pieces of Earth-orbiting debris is the responsibility of the 18th Space Control Squadron at Vandenberg Air Force Base. The debris creates a threat to functioning satellites and sometimes Earth. Twice this year, major pieces of a Chinese rocket body have lost power and fallen from orbit to crash back down into the Pacific and Indian oceans.

“It’s become more than apparent that anyone and everyone who puts up a satellite or any other instrument in space has a responsibility as a good space steward to do their part to mitigate against adding any more space debris,” said Rich Cooper, vice president for strategic communications for the Space Foundation.

The WISA Woodsat is not entirely made of wood, just the outer shell. The edges and camera boom are 3D-printed extremely light metal plates, and under the wood panels will be small electronic boards. But those components are also anticipated to burn up to the point where they would leave minimal trace, Rampini said.

ESA will also use the flight to test a quartz crystal microbalance sensor and super-sensitive pressure sensor in space before using those on other missions, Mäkinen said.

The WISA Woodsat measures 10 by 10 by 10 centimeters, which is small enough to hold in your hand, and is based on Arctic Astronautics build-your-own “Kitsat” cubesats the company invented to provide inexpensive research tools to educators.

ESA worked with Arctic and UPM to test and modify the birch plywood modified to withstand low-Earth orbit conditions. At that altitude, about 600 kilometers up, the plywood will face a constant bombardment of highly corrosive atomic oxygen, which will eat away at the surface much like a sandblaster beats bricks, Rampini said.

Just like plywood does in new construction, the wood will release vapors in a process known as “outgassing.” That could affect the satellite’s instruments. The Woodsat’s camera will record how well the satellite stands up.

“The first couple of months will be the most interesting months for the outgassing because this is where you have the highest peak,” Rampini said. “If it survives two years, that would be good.”

Mäkinen had not expected to launch a wooden satellite into space this year.

When they learned in December 2020 that Japanese firm Sumitomo Forestry was working with Kyoto University to become first to launch a wooden satellite into space, the company hustled.

Finland-based UPM, one of the world’s largest forestry firms, quickly became a sponsor.

“At that moment, I don't know whether they panicked or not,” Rampini said. “They called us.”

“We are now here with a real satellite, practically ready to fly,” Mäkinen said.