This undated file image posted on a militant website on Tuesday, Jan. 14, 2014 shows fighters from the al-Qaida linked Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) marching in Raqqa, Syria. The ISIL led by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who is believed to have been AP

The Government Probably Has More Photos of You Than of ISIL's Leader

The U.S. government probably has more biometric information on you than one of the most infamous terrorist masterminds alive. By Patrick Tucker

In 2005, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the man today considered the leader of the Islamic State of Syria in the Levant, or ISIL, fell into the custody of United States forces in Iraq. A U.S. soldier subjected him to a finger and iris scan using the Biometrics Automated Toolsets System or BATS, a laptop with device peripherals hanging off to the side. That soldier also would have entered a few other biographical details like name, origin and occupation, etc., into the system. Shortly after that, Baghdadi was sent to Camp Bucca where he would have been photographed, possibly five times, from the front, the side and at angles. Someone would have taken down his height, weight and any visible scars on his body. Baghdadi would live under U.S. custody at Bucca for another 4 years before his 2009 release whereupon he uttered the now famous warning to his captors: “I’ll see you guys in New York.”

Today, Baghdadi has a $10 million bounty on his head. Military leaders and TIME magazine consider him to be the “most dangerous man in the world.” In the ongoing effort to identify and find the leaders of ISIL, a requirement to taking out the group’s leadership with air strikes, Baghdadi stands out as the most potentially valuable military target on the planet. He may be in Syria now, or Iraq, but probably not far from there. “He’s a hometown boy,” said Patrick Skinner, a former CIA analyst who was in Iraq at the time of Baghdadi’s capture. With Baghdadi in the hands of the U.S. for so long, with such ample opportunity to gather clues, signatures, data, why doesn’t the U.S. know how to find him, now?

That answer has many parts but one is that, according to Skinner, the U.S. simply didn’t collect much biometric data on Baghdadi when officials had the chance. In fact, the U.S. government probably has more biometric information on you than one of the most infamous terrorist masterminds alive.

Go to any airport and you will be photographed dozens of times from the moment you approach the parking lot to the second you step on the plane. We accept the vigilance of cameras in our environment, shooting pictures of us from above and below, performing what some in the field of biometrics call non-permissive data collection. Non-permissive sounds far darker and more Orwellian than permissive. In fact, permissive biometric data collection in war zones was “usually a knee-to the back as we pull somebody’s arm behind him to get a fingerprint,” John Boyd, director of Defense Biometrics and Forensics, told the Biometrics for Government summit in February.

Non-permissive data collection is an inescapable feature of the modern urban landscape. In the city of London, there’s one closed-circuit camera for every 32 citizens. You could be forgiven for finding some irony in the fact that at Camp Bucca, a tightly controlled environment, constant photography of prisoners for biometric facial recognition was not the common practice, according to Skinner.

“They’re not going to take a lot of pictures…Abu Ghraib taught them, you probably want to restrict that,” Skinner says, referring the 2003 scandal at Iraq’s central prison in which U.S. contractors photographed themselves sexually abusing inmates, among other crimes. Post scandal, walking into a U.S. run Iraqi prison was “like going into a hospital,” he says. One result of that, despite having access to him, we may have very, very few photographs.

Kevin Haskins, a business development manager with the company Cogitec says that the publically available picture of Baghdadi from Bucca would be sufficient to match him against a suspect, with high confidence, even at a good distance, so long as Baghdadi was facing straight ahead or not more than 10 degrees up or down, or 30 degrees to the right or left (considered the upper threshold of current facial recognition technology). But an abundance of pictures from more angles would be useful in identifying him in more situations, in a natural environment.

“If we had ten pictures of him in the database, it is more probable that he would get matched on the ten to the one. With more images for comparison, the probability goes up,” he told Defense One.

That doesn’t mean that Baghdadi lends himself to an easy interception in the wild via drone or human intelligence, but more pictures to better train facial recognition algorithms on him could make that interception easier.

Consider that for a moment, the U.S. did not allow itself to better photograph the most dangerous man in the world when

he was in our custody but had he just gone to a bank, to a convenience store in any city in the United States or Europe, had he just opened a Facebook account, the U.S. would have the opportunity to collect a much better photographic data set for him.

Experts point out that this sort of Person of Interest capability just wasn't the intent of biometric data collection at the time. The most that could be hoped for was to match a suspect either already in custody or at a check point, or someone attempting to gain access to a base to an individual in a database. “There’s a major difference between that and taking a photo of someone in the market square and saying ‘here’s our guy,” Troy Techau, the director of biometrics at U.S. Central Command from 2003 to 2007 told Defense One.

Researchers at the forefront of the field understood the value of biometric identification in terms of categorizing people that the U.S. was in contact with. Techau says it allowed them to understand who they were dealing with in the field much better. But they were frustrated by the limitations of the technology and knew there was a lot of potentially useful information that was being left out of the record. “We had conversations in 2003, 2004 and 2005 about precisely this situation,” said Techau. “We said, ‘This guy may be nothing now, but where’s he going to be ten years from now?’”

Techau questioned the utility of different photo resources from 2005 in pursuing Baghdadi in 2014. “Having other photographs, such as having a surveillance camera on him as he wandered around Camp Bucca for four years as a prisoner, what good does that do you? You’re getting an oblique angle with low pixel count,” he said. “Most of the surveillance cameras we had back then weren't digital. So what are you going to get? I’d bet that an analog surveillance camera capturing a whole room of detainees, maybe eating in the chow hall, the pixel count between the eyes will be very low. So could you take that low level photograph and match it against a high-resolution photos of when he was enrolled in the system? Probably not. Those photos have limited value,” said Techau.

“I would not be surprised if there were decent photographs of this guy, good fingerprint data on this guy. I’m sure we have DNA. But taking that as a tool to find him today? Using a biometric to find a needle in a haystack? Until we get to the point where the reliability of facial detection from a drone, flying along, to be able to take a quality enough photograph from an aerial platform, you need a quality collection with enough features that a matching algorithm can put it against a database and not have so many false positives that it’s useless. Using Today’s technology that dog ain’t going to hunt.”

But the U.S. began collecting biometric data on individuals like Baghdadi not just for the difficult task of finding them, but also to meet the more simple challenge of denying them access to U.S. bases and equipment. This is something that the military refers to as access control and it’s a key component of the reason the U.S. used biometrics in places like Iraq.

“Quite frankly, we spend many hundreds of millions of dollars in DOD, actually more than that just in the Army, for gate guards,” said Boyd. “So there’s both a ‘How can we do this better to verify what’s coming in, and ‘if we can automate it to the point where there are fewer gate guards,” as justification for more biometrics.

Today, Baghdadi’s organization controls a frightening cache of U.S. vehicles and other arms (in various states of repair) that were left behind by the fleeing Iraqi Army. Some photos indicate that they may be in possession of Humvees and U.S. stinger missiles. It would make ISIL not only the richest terrorist organization in the world but also the best armed.

While DOD is continuing to invest in some biometric programs to face enemies like ISIL, overall spending is down and Boyd worries new priorities like the pivot to Asia could affect the military’s ability to find or capture the likes of Baghdadi.

We can capture the world’s most dangerous individuals, log the most intimate details of their biological functioning into databases, record the dimensions of their eyes and irises, blood and genes, and share that information nearly instantly anywhere on earth but we’re helpless to prevent terrorists from stealing our stuff.

Additionally, the U.S.’s our ability collect biometric information on potential threats is strongest in those places where we face no threat, namely at home.

“If he was in America or he was in Europe, we could find him in a heartbeat,” says Skinner. “But we’re not interested in people in London right now. The chaos is in the Middle East.”

We have biometric technologies to detect pulse and eye dilation at close range and movement signatures at a distance. It’s wonderful technology but it “only works if you are in a place with the infrastructure to have cameras,” said Skinner. “Technology depends on old fashioned bureaucracy, electricity, standards and very literal stability. That is not Iraq and Syria. It won’t be for a long, long time.”

No one believes that biometric information alone could have kept Baghdadi from taking Mosul, or ISIL from capturing U.S. equipment, but at some point, whether it is Iraqi forces, the U.S., or an allied contingent someone will need to stop Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. To do that, we need to identify him. It’s a task that may have been easier if we had used capabilities that are common and accepted here at home in the field in Iraq. Or perhaps the technology at the time simply would not have allowed it. But it might in the near future.

So long as he stays in either Syria or Iraq, we have little chance of finding him. But should Baghdadi make good on his threat to come to New York or any other city in which the occupants, afraid of distant threats, have learned to accept constant surveillance, our chances for finding him would improve.

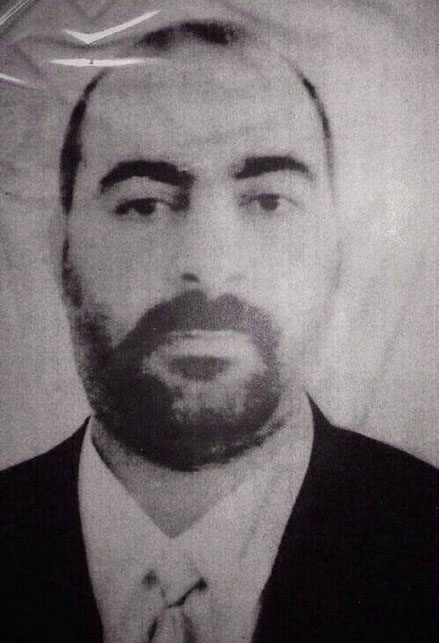

Undated picture released on Wednesday Jan. 29, 2014, by the official website of Iraq's Interior Ministry claiming to show Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the head of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Courtesy of AP

NEXT STORY: There’s No Such Thing as ‘NSA-Proof’ Encryption