The Border Patrol’s ‘Constitution-Free’ Zone Is Probably Larger Than You Think

All of Michigan, D.C., and a large chunk of Pennsylvania are part of the area where Border Patrol has expanded search and seizure rights. Here’s what it means to live or travel there.

Arivaca is a small, unincorporated community in Pima County, Arizona, around 11 miles north of the Mexican border. The closest big city is Tucson, 60 miles northeast. The town itself is barebones—a smattering of old buildings, some dating back to the 1800s. It is surrounded by swathes of yellow grassland.

To get groceries or cash a check at the bank, residents often have to drive north to Green Valley, or even further, to Tucson. And to do that, they have to pass by a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) checkpoint, where they’re inevitably asked if they’re U.S. citizens.

“It sometimes feels like they’re trying to create a no man's land,” says Arivaca resident Peter Ragan. “All the people who are living here, and may have lived here for generations, are now part of the problem because they're in the way.”

While the weight of border patrol’s operations is felt heaviest along the southwest border of the U.S., the “no man’s land” Ragan is talking about actually extends much further into the country. In the “border zone,” different legal standards apply. Agents can enter private property, set up highway checkpoints, have wide discretion to stop, question, and detain individuals they suspect to have committed immigration violations—and can even use race and ethnicity as factors to do so.

That’s striking because the border zone is home to 65.3 percent of the entire U.S. population, and around 75 percent of the U.S. Hispanic population, according to a CityLab analysis based on data from location intelligence company ESRI. This zone, which hugs the entire edge of the United States and runs 100 air miles inside, includes some of the densest cities—New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago. It also includes all of Michigan and Florida, and half of Ohio and Pennsylvania, according to a prior rough analysis by Will Lowe, a data scientist at MIT.

The first of the three maps ESRI created for CityLab show the population density within the 100-mile zone:

“It really is kind of a constitution-free zone,”says Patrick Eddington, a policy analyst who has been compiling data on border patrol’s internal checkpoints at the CATO Institute, a libertarian think tank. “I guess the best way to phrase it is that in this area, [border patrol agents] are being allowed to nullify people's rights.”

According to critics, checkpoints and other internal operations in the 100-mile zone aren’t serving their intended purpose: Just 2 percent of CBP’s total arrests of deportable non-citizens happened at checkpoints. And since 2010, far more people who had legal status and weren’t eligible for deportation were arrested this way. Meanwhile, individuals in this zone—citizen or otherwise—are at risk of having their Fourth Amendment rights violated by border patrol, critics say.

The law within the 100-mile zone

On his ranch near Laredo, Texas, a man named Ricardo D. Palacios discovered a CBP surveillance camera and recently sued the agency—complaining of longstanding harassment and trespassing. The case gets to the heart of Border Patrol’s authority beyond the immediate border. At its core, the law allows immigration officers to access private lands—except “dwellings”—within the 25 air miles (28.7 miles) of the border.

Congress also authorized CBP to set permanent and temporary checkpoints, patrol highways, and board buses, trains, and other vehicles “within a reasonable distance” of the U.S. border, which regulations in 1953 set as “up to a 100 miles.”

These regulations were made to allow border officers to intercept unauthorized entrants who had bypassed checks at ports of entry.

“The vast majority of CBP personnel and assets are stationed at the border itself; however, in our mission to safeguard America's borders, we have a responsibility to track routes into the interior of our country for those who evade capture,” CBP spokesperson Dan Hetlage told CityLab via email.

CBP can set up checkpoints anywhere it wants within the 100-mile zone and “can temporarily seize all vehicles that drive up to an immigration checkpoint... to conduct an immigration inspection,” a spokesperson said. If they feel they have probable cause, they can search the vehicles. Agents at checkpoints also have wide discretion to pull people aside for a secondary inspection, which could last, per some accounts, for up to 40 minutes.

Agents in patrol cars are permitted to stop motorists in the zone based on suspicion that they have committed an immigration offense, and can also check individuals’ papers on buses, trains, and airplanes. CBP says the transit checks are conducted “as consensual encounters.” That latter aspect of CBP powers has come to the fore in recent months, after videos surfaced showing CBP agents checking papers on Greyhound buses, Amtrak trains, and airports seemingly far from the Southern border. (The ACLU has recently launched a campaign asking Greyhound to deny CBP the permission to board their buses.)

But these sorts of checks aren’t new. In 2013, a study released by NYU Law’s Immigrants’ Rights Clinic found that between 2006 and 2010, border patrol agents in Rochester regularly checked people at transit hubs, and in the process, had arrested 300 people with legal status—international students, refugees, and other immigrants included. (The report also mentioned that agents were promised Home Depot gift cards and other incentives in exchange for amping up arrests.)

As Vox’s Alexia Campbell explains, individuals are not required to answer CBP’s questions at checkpoints or other inspections, but may be detained for refusing. On YouTube, several videos have been posted documenting tense exchanges between agents and American citizens who have declined to answer questions.

“[U.S. citizens in these videos] don't understand why their rights as Americans don't encompass going from point A to point B in the U.S.—far from the border,” said Chris Rickerd, a policy counsel at the ACLU. “The checkpoints are very controversial, and not only from a civil liberties perspective.”

The law within the 100-mile zone allows for profiling

So what criteria do agents use to decide to stop a motorist or traveller? Can they use a person’s race or ethnicity? Yes, as long as it’snot the only factor, according to one Supreme Court ruling from the 1970s. In 2000, however, the 9th Circuit court of appeals, which covers the border states of California and Arizona, rejected “any reliance on Hispanic appearance or ethnicity” in making roving patrol stops, citing the changing demographics of the country. It remains to be seen whether this precedent will be applied elsewhere.

“That’s really significant because many of the border enforcement mechanisms just don't catch up to the reality of life at the border,” ACLU’s Rickerd said.

CBP and DOJ guidance also allow border patrol agents to profile under certain conditions—a remarkable fact given that 72 percent of the U.S. minority population lives in the 100-mile zone. Some of the highest concentrations are in areas where the border patrol presence is the heaviest.

The below map shows minority share of the population within the 100-mile zone. There are almost two times the number of people of color inside the zone and three times the number of Hispanics, compared to the non-border zone portion of the country:

What do border checkpoints accomplish?

Four years ago, some Arivaca residents started documenting border patrol’s interactions with locals. Ragan and some others from the local humanitarian organization People Helping People In The Border Zone analyzed 2,000-plus interactions, and found that vehicles with Latinos in them were 26 times more likely to be asked for ID than white motorists. They were also 20 times more likely to be sent in for a secondary inspection.

“We really feel like these checkpoints serve to, over and over again, scrutinize and criminalize the local population, rather than provide some kind of real bulwark against undocumented immigration,” Ragan said. He and his group have been pushing for the removal of the checkpoint. They have sued CBP from blocking them from keeping tabs. Recently, a court allowed their case to proceed.

Border patrol maintains that checkpoints are “vital to fulfilling CBP’s immigration mission.” While the Trump administration has emphasized the need for expanding the border wall, some Border Patrol agents have complained that might draw resources away from internal checkpoints, which they say have been successful in stopping the smuggling of people and drugs.

“They’re taking money away from proven law enforcement systems to put it into this 14th century solution,” Representative Henry Cuellar, a Democrat from Laredo, Texas, told the Associated Press. He believes that more federal funds should go towards updating technology at the Laredo North checkpoint.

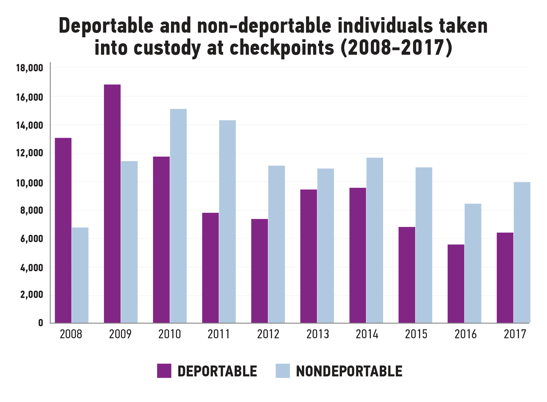

But CBP’s own data, government watchdog reports, and recent lawsuits have raised some questions about the efficacy of checkpoints. In 2017, the 6,595 deportable individuals arrested at checkpoints made up just 2 percent of the total CBP arrests of non-citizens that year. Between 2008 and 2018, many, many more people with legal status were taken into custody at the internal checkpoints—some years, almost twice as many (in the chart below). During the same period, apprehensions of people who are deportable dropped by 50 percent. CBP declined to comment on whether U.S. citizens were also taken into custody at these checkpoints, and if so—how many.

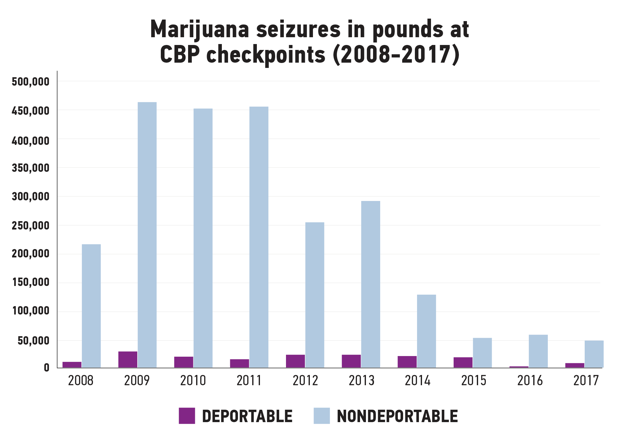

What checkpoints seem to be good for, however, is intercepting drugs—mostly marijuana—from people who are legally present in the U.S. Snoop Dogg, Armie Hammer, Willie Nelson, and Fiona Apple are among the American celebrities who’ve been ensnared at CBP checkpoints for this reason.

CBP defines “deportable” as someone who can be removed from the country based on Section 237 of the Immigration and Nationality Act . A “non-deportable” person is a non-citizen not eligible for deportation. This could be a permanent resident, valid visa holder, or someone with another type of legal status. (Madison McVeigh/CityLab)

According to CBP’s data, agents seized 54,803 pounds of marijuana at internal checkpoints in 2017; 90 percent of this was from individuals who were lawfully present in the country. (CBP also seized cocaine and heroin, but in much, much lower quantities.)

Marijuana seized at government checkpoints. (Madison McVeigh/CityLab)

A 2017 Government Accountability Office (GAO) review of checkpoints requested by Congress also found that arrests at these sites between 2013 and 2016 were a drop in the bucket—2 percent of total arrests of unauthorized entrants in that time. They also found that 40 percent of all drug seizures at checkpoints were for 1 ounce or less of marijuana from U.S. citizens.*

“There is a mentality operating that says these checkpoints are essential to countering illegal immigration and all the data of course says exactly the opposite,” CATO’s Eddington says. “It says that they're completely ineffectual at actually stopping illegal immigration. Instead, they're great at catching Americans with dime bags of weed.”

CBP maintains that checkpoints aren’t sites for general crime-control—that would be unconstitutional. But this month, a New Hampshirejudge found that CBP had set up a checkpoint near a Cannabis festival in Woodstock, and colluded with local law enforcement to hand over individuals with small amounts of marijuana—violating the state and federal law. “This court finds that while the stated purpose of checkpoints in this matter was screening for immigration violations the primary purpose was detection and seizure of drugs,” the judge’s opinion reads.

“I suppose by their logic, we should just set up checkpoints all across the United States on every road and we'd be intercepting a lot more drugs,” Arivaca’s Ragan says. “But we won't be much of a democracy anymore.”

They “don't want to touch this with a ten-foot pole”

In border communities, the presence of checkpoints has been a long-simmering political issue. Until 2007, a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Arizona, Jim Kolbe, had mounted a strong resistance against checkpoints—withholding congressional funds for permanent ones in his constituency. He considered them ineffective and intrusive. “To say to people who live near the border that even though you’re American citizens, you’re going to be disturbed every day—that’s unacceptable,” he told the Texas Observer in 2009. But after he retired, Arizona’s checkpoints became permanent—to the relief of border patrol officials.

”It was an idea that always confounded people familiar with the Border Patrol's operations—as to why Mr. Kolbe insisted on tying our hands,” T.J. Bonner, former president of the border patrol union, told the Arizona Daily Star in 2006.

There’s unlikely to be pushback on this front from GOP members in the near future, especially given the success of the current administration’s immigration agenda. Lawmakers “don't want to touch this with a ten-foot pole,” CATO’s Eddington says, for fear of appearing soft on immigration.

Going forward, some civil rights advocates worry that cases of excessive use of force, or even death, may increase as hiring standards loosen, and more agents and resources get funneled into the border zone. (According to an investigation by The Guardian, Border patrol operations led to 97 deaths over the last 15 years—some 160 miles from the border itself.)

But even if that worst case scenario doesn’t materialize, activists and residents near the border see the mere presence of these checkpoints as cruel and inhumane. For undocumented or mixed-status families, they create impossible, Hobson’s choices. Should an undocumented Texan woman exercise her already-restricted right to have an abortion, if there’s a checkpoint on the way? Should undocumented parents take themselves and their kids to get crucial medical treatment if there’s a checkpoint on the route to the hospital? Or, should they stay home and risk the consequences of not getting help?

“These checkpoints? They're borders themselves—they separate families; they separate communities,” said Jorge Rodriguez, an ACLU organizer in Southern New Mexico.

*It’s worth taking all the numbers provided by CBP with a grain of salt because the GAO also found “inconsistent data collection practices at checkpoints.”