How to Reconnect the Pentagon’s Strategy to its Budget

Biden will have little time and likely less money to enact his policies. He needs to tie strategy more closely to funding.

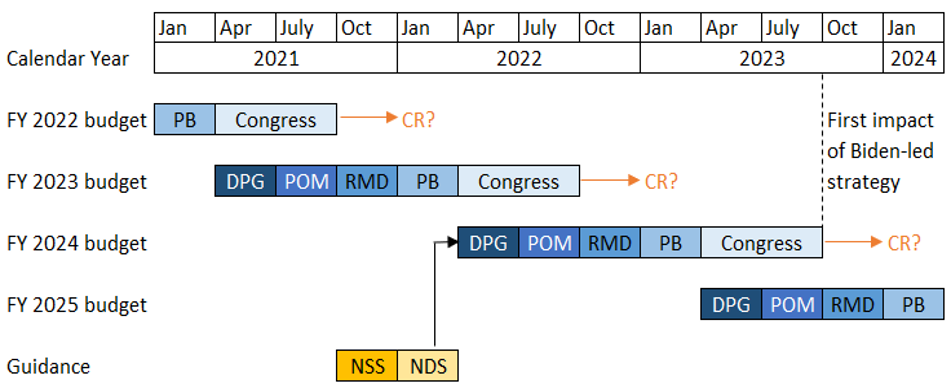

After Donald Trump entered the White House in January 2017, it took a full year before his administration released a National Defense Strategy. By that time, the 2019 budget proposal was nearly finished, and so 2020 was in many ways the first year to reflect Trump’s military policy. The Biden administration can expect similar timelines to prevail — yet Biden cannot expect the same kind of financial support as Trump. Over the last four years, Congress sent the Defense Department some $440 billion more than had been planned for in the 2016 request. With budget challenges ahead, the DoD will require a strategy more closely linked with fiscal realities to enable the lower levels to make difficult tradeoffs.

It will likely take a while for Biden’s military strategy to translate into budgets.

Key: DPG: Defense Planning Guidance. POM: Program Objective Memorandum.

RMD: Resource Management Decision. PB: President’s Budget.

NSS: National Security Strategy. NDS: National Defense Strategy.

CR: Continuing resolution.

One of the problems of translating strategy into budgets is that the National Security Strategy and the National Defense Strategy use vague language in a bid to exercise top-down control yet grant flexibility at lower levels. Most of the strategic guidance does not directly relate to specific programs already planned five years out in the Future Years Defense Program.

One path forward is to link strategy with budgets starting with the National Security Strategy, precisely because the Program Objective Memorandum already has a five-year baseline plan. Without establishing budget ceilings, it is easy for defense officials to look at their program plans and connect that with vague strategic guidance.

As funding declines, greater specificity in the NSS and NDS may provide top-cover for cuts. Attempts to reprioritize funding toward emerging technologies and concepts of operations have not been met with overwhelming success. Efforts to re-evaluate past budgetary decisions in light of great power competition — think DoD’s Night Court — come into play late in the cycle, operating mostly on the margins of the defense spending. Other efforts that operate from within the government framework often encounter the same pressures towards imprecision as the strategic documents themselves—like the Future of Defense Task Force, which answered a call for a study about divesting and realigning defense programs, but not dollars or timeline.

The NSS and NDS should specify dollar thresholds for reallocation to keep pace with diminished funding. Doing so will demarcate areas of emphasis, and will underscore with greater certainty which tradeoffs should occur at lower levels. For example, the NSS could specify how much money to shift from research and procurement of existing systems to emerging technologies and operational experimentation. The subsequent NDS could subdivide the broad mandate into capability portfolios — say, less for manned aircraft and more for battle networking. New consolidated budget line items could then be requested to those capability areas, as opposed to individual projects, allowing lower levels to maximize within the bounds of the mandate.

The top-down allocative process assures that decisions are made at the right level. Even though the DoD may object to budgetary decisions being made by participants on the NSS, it remains at an aggregate level and does not affect any program in particular. The concept has strong foundations in successful a World War II resource allocation system: The Controlled Materials Plan. Before the plan, every company submitted its requirements for scarce materials like copper, aluminum, and steel. This produced a tremendous flow of paper and made it impossible for examiners to make selective cuts. Companies inflated their requests so much that the demand for copper was three times the world supply. The Controlled Materials Plan reoriented to a vertical allocation process. The civilian War Production Board allocated large blocks of funds to claimants like Army, Navy, Aircraft Scheduling, Lend-Lease, and various civilian agencies. The claimants would subdivide to down their organizations, to the prime contractors, and from there through the supply chain. The process was a resounding success and provides crucial lessons for allocating defense resources in the 21st century.

One of the truisms of defense management is that strategy and budgets must be connected. A “wish list” strategy that results in endless unfunded requirements will not result in the same outcomes as a strategy that considers fiscal realities. Today’s requirements-pull process has strategy defined separately from budgetary considerations, which reflects the DoD’s resource allocation system. If everything is important, then nothing is. That allows the DoD’s baseline plan in the Future Years Defense Program to continue on cruise control.

The FY 2021 outyear plan, however, presumed budgets would steadily rise from $712 billion in FY 2020 to over $779 billion in FY 2025. If that plan proves optimistic, then it is likely the recent forays into emerging technology will suffer the consequences. If gearing up for great power competition is the preeminent priority, then it is time for strategy to protect and grow its modernization programs. If they are cut, leaving a new generation of defense entrepreneurs to fail, then it will be another generation before the DoD can credibly build an innovation ecosystem.

Eric Lofgren is a research fellow at the Center for Government Contracting at George Mason University. He manages a blog and podcast on weapon systems acquisition.

Stephen Rodriguez is a Managing Partner at One Defense, Senior Advisor at the Atlantic Council, and Senior Innovation Advisor at the Naval Postgraduate School.

NEXT STORY: The Dangers of Nuclear Virtue Signaling